In a couple of months, the soaring slopes and ridges between Dolores and Rico, Colo., will burst with new life, from wildflowers to fawns.

Flocking to enjoy the views, the blooms and the fresh air will be outdoor enthusiasts of all stripes — hikers, mountain-bikers, horseback riders and motorcyclists.

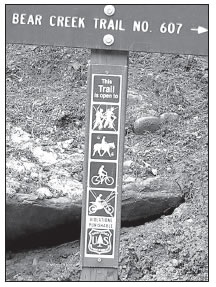

A sign at the Bear Creek trailhead demonstrates the contentiousness of travel-management issues in the area, as some of the icons have been scratched off. Photo by David Grant Long

But the question of who will be able to go where is unanswered at the moment.

That’s because the plan that was to guide and regulate different types of travel on San Juan National Forest lands in the Rico- Dolores area was essentially scrapped late last year — remanded on appeal to the Dolores Public Lands Office for another try.

“We’re going to reinitiate the [planning] project after Oct. 1,” said Steve Beverlin, district ranger for the Dolores District of the San Juan. “We’ll start all over, utilizing existing information and data we have. There’s some good stuff in there [the plan] that we’ll use, but basically it’s back to the drawing board.”

Beverlin approved what was supposed to be the final travel-management plan for the 244,550-acre Rico-West Dolores area in September 2009. However, six separate parties appealed the decision, charging among other things that the DPLO had not conducted adequate analyses, had not adequately informed the public about some decisions in the plan, and had violated the overall forest plan by designating some trails as motorized within nonmotorized areas.

After reviewing their concerns, a Forest Service appeal-reviewing officer sided with the appellants on most of the charges and recommended remanding the plan to the DPLO. Of 15 specific issues cited by the appeal officer, he recommended reversing the manager on 11 and affirming the manager’s decision on the remaining four.

San Juan National Forest Supervisor Mark Stiles concurred and in December 2009 reversed “in whole” the approval of the plan. “The Manager is directed to review the concerns . . . and to take appropriate action to address them. . .,” Stiles wrote.

In a March 18 e-mail to interested parties, Beverlin stated that the DPLO, San Juan Public Lands Center and Forest Service Regional Office had decided to start the new effort after Oct. 1.

The DPLO will have to “re-scope” the project, meaning do new outreach and take more public comments. All scoping comments from the original project will also be used in the new analysis, Beverlin stated.

The area will need interim management guidelines in place before late May or early June, when heavy recreational use begins, Beverlin said in the e-mail, and those guidelines will be decided by the three Forest Service entities. “We’re all working together,” Beverlin told the Free Press.

Also still to be decided is whether the new planning effort will entail doing an environmental assessment or a more intensive environmental impact statement — one of the major bones of contention in the appeal of the first travel plan.

In his recommendations, the appeals officer, Robert Sprentall, wrote that one of the common issues of the different appellants was their belief that an EIS should have been prepared instead of the EA that was done. “I recommend reversing the Managers [sic] decision on this point,” Sprentall wrote.

However, Beverlin told the Free Press that the question of whether to do an EA or an EIS “will be decided later. We’ll decide that some time before we reinitiate this project.”

He said an EIS has more requirements for public scoping and usually offers a longer comment period, but is not substantially different from an EA. Beverlin said it’s common for appellants to argue that an EIS should have been done. “We get that issue every time we have an appeal,” he said. “So we step back and look.”

‘Most divisive’

Travel management on public lands is tremendously controversial nationwide, largely because of the conflict between motorized and non-motorized recreation.

The thorniness of the issues involved is demonstrated by the fact that the Rico- West Dolores plan was appealed by five parties concerned about the expansion of motorized uses (the San Juan Citizens Alliance, former Montezuma County Commissioner Gene Story, a Montezuma County couple, Trout Unlimited- Colorado Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, and the Dunton resort) — but also by the Blue Ribbon Coalition, which advocates for motorized recreation.

“The Rico-West Dolores Travel Management Plan has been the most divisive and difficult issue I have dealt with since I became the District Ranger/Field Office Manager for the [DPLO] in August of 2005,” Beverlin wrote in the decision notice for the now-remanded plan.

The DPLO has been working on travel management plans for four areas: Mancos- Cortez, Rico-West Dolores, Boggy-Glade and a BLM-managed landscape that includes Dry Creek, Big Gypsum and Disappointment Valley.

The Mancos-Cortez plan was finalized in September 2008 without much fanfare and with only an EA having been done. There was one appeal, according to Beverlin, but the plan was upheld. The office is working on the Boggy- Glade plan and hopes to have a preliminary EA released by the middle of this month. Work will begin later on the Big Gypsum-Disappointment landscape.

Travel management isn’t the only controversial issue that public-lands managers have to deal with, Beverlin pointed out — oil and gas development, grazing, wilderness, and wild and scenic rivers are all contentious. But travel management is “toward the more-contentious end,” he admitted.

The trails that snake around the Rico- West Dolores area are generally narrow and steep, winding through grassy meadows and aspen forests and teetering along high ridges. They are cherished by hikers, hunters, wildlife aficionados and horseback riders.

They are also embraced by motorcyclists, who relish the challenge of maneuvering around hairpin turns, over rocks and through streams. A 2008 video showing motorcyclists grinding along the district’s popular Calico Trail can be seen on YouTube (search under Motorcycle Ride Calico Trail).

The motorized users, it’s fair to say, raise a lot of dust — and a lot of hackles.

“I’ve had hunts destroyed by motorized users,” said Bob Marion, who with his wife, Nancy, was one of the parties that successfully appealed the Rico plan. “You can be out in an area hunting, and if a motorcycle rider comes through a trail just once a day, you won’t find an elk in that region for at least a couple days. I’ve had that happen.

“I’ve had encounters where they [riders] actually tried to run me off the trail. My personal experience has not been good.”

The Marions, both retired, are residents of Montezuma County. “We spend probably 160 to 180 days a year in the outdoors, and a lot of it is up in the Dolores drainage,” he said. “I hunt a lot. We fish, hike, cross-country-ski, mountain-bike — about all the quiet-use activities.”

But Marion said he is definitely not trying to have motorized users eliminated from the area. “To me it’s not an issue of, are you in favor of motorized or against,” he said. “I think we need to reach a happy medium between providing single-track motorized trails and also protecting habitat for wildlife and so on.”

However, he believes many of the trails in the Rico-West Dolores area were designated for motorized use without the appropriate NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) process being followed, and this prompted him to take action.

“This is our first time to file an appeal,” Marion said. “We’re individuals, not an organization. My wife and I are concerned citizens.

“We think we know the issues quite well and I think what’s been done over the past years has not been done in compliance with Forest Service policies, procedures and laws.”

Doing damage?

Steve Johnson, attorney for Dunton, LLC, which owns the Dunton Hot Springs Resort and several other properties in the West Dolores area, agreed.

“When we saw the one-sided, non-scientific, poorly documented decision, we had to file an appeal,” he said.

One of the main points raised by those appealing was that certain trails such as Priest Gulch, Stoner Creek, Johnny Bull and Wildcat, which have permitted motorized uses for some time, became motorized without the Forest Service having gone through the requisite legal process.

Such trails lie within portions of the forest that are currently designated as “semiprimitive, non-motorized.” While such areas are sometimes allowed to have motorized corridors going through them, an appropriate NEPA process has to be followed first, something several of the appellants contend was not done.

“We don’t believe the motorized designations have ever gone through the NEPA review process,” Johnson said.

“We think there has been a bias in the [Dolores Public Lands] office in favor of motorized uses and designations. More and more trails have been getting signed for motorized use in the Rico-Dolores area, through the 1990s and beyond. We’re very concerned about the trend.”

Dunton is a private resort located off the West Dolores Road between Dolores and Rico. It specializes in a remote, quiet experience for its guests, Johnson said, and motorized users on nearby trails threaten that experience.

Dunton has seen “numerous instances of motorcycle trespass,” he said. Riders coming down the nearby Fall Creek Trail, which dead-ends above Dunton, sometimes try to ride through the Dunton property; when stopped, they may become angry. “There have been incidents, threats and even altercations,” he said.

Motorized users are also causing widespread damage, Johnson contends.

One nearby trail popular with the resort’s guests is the Winter Trail, which extends from the Calico trailhead. “The Winter Trail crosses numerous side streams, beautiful little streams,” he said. But over the years, motorcycles have created bogs, pits and mud holes in the trail to the extent that you “can’t even mountainbike there,” Johnson said. Water left standing in the mud holes eventually saturated nearby tree roots and killed the trees. Johnson said the Forest Service was slow to respond to the damage, finally putting planks across the bogs that are often slick and dangerous for horses or hikers.

Beverlin, however, sees it differently.

“Dunton [workers] took photos of that trail and stood on the planks, so they didn’t have any problem hiking it,” Beverlin said. “We’re comfortable with how the Winter Trail is maintained. There are three small, very minor parts [with problems] but the other 98.7 percent of the traill meets our standards.”

He said it’s not unusual for trees to die and fall down even when human activity is not involved. “All the snow we’ve had may cause trees to fall over because the soil is saturated. It’s a natural process.”

‘A lightning rod’

Many of the public comments and much of the debate involve the Calico Trail, a 19- mile route described in the DPLO’s decision as “a lightning rod in this decision” and “the backbone of the skeleton” because so many other trails intersect it.

It is the highest-elevation motorized trail on the San Juan National Forest, according to the decision, and “provides a high quality, technically challenging, and diverse experience with loop opportunities” for motorized users.

The uppermost reaches of the Calico Trail are above timberline, climaxing at Sockrider Peak, elevation 12,150 feet. The trail then descends southward to the Priest Gulch trailhead.

Under the travel plan, Calico would remain motorized, a fact that some of the appellants found troubling.

“The top five miles of the north Calico Trail and adjoining meadows are widely acknowledged as trashed from single-track motorized and historical ATV uses,” wrote Johnson in Dunton’s appeal.

Mike Curran, a member of the Rico Alpine Society, a nonprofit volunteer group based in Rico, told the Free Press the society is concerned about damage to Calico. “That’s ne of our biggest concerns at this point, not just the fact that it’s designated for motorized use, but the fact there’s so much resource damage been occurring. We’d just like to see it addressed more than it has been.”

The Division of Wildlife expressed concern about Calico in a Feb. 7, 2008, letter submitted during the original public scoping period for the travel-management plan. Patt Dorsey, area wildlife manager, wrote, “We urge the USFS to restrict motorized use of this trail as it is not compatible with and is dangerous to other users such as horseback riders. It is a steep trail above timberline and erodes easily damaged soils and delicate vegetation. Numerous people have driven off of the trail above timberline. . . Motorized vehicle use on this trail also inhibits wildlife use of this important habitat by increasing fragmentation. The trail bisects important elk habitat. . . .”

In a June 5, 2009, letter in response to the release of the preliminary EA, Dorsey wrote that the Forest Service’s preferred alternative “addresses few of the concerns” cited in her earlier letter, and urged that, among other trails, the Calico and Lower Calico trails should be designated as nonmotorized. However, the final decision allowed Calico to remain motorized for its entire length, except for a quarter-mile that was to be re-routed around a mining claim.

In the decision notice for the travel plan, Beverlin stated there was “rutting in wet meadows at the northern end, and other isolated wet and rutted areas along the Calico and associated trails” but said the Rico-West Dolores trails are generally in good condition. Beverlin also wrote that he had prioritized the northern Calico Trail for future maintenance.

“That trail is 19 miles long and along that length there’s sore spots that need to be fixed, and that’s what we’re doing,” Beverlin told the Free Press, “but overall it meets our trail standards for maintenance.”

He said it’s the lower, wetter sections near the trailhead (just off Forest Road 471, at the southern edge of the Lizard Head Wilderness Area), which are heavily used by both motorized and non-motorized recreationists, that typically see damage and draw complaints because most hikers don’t go more than a couple of miles from the trailhead. “They see the area that’s heavily used and not those middle sections that are maintained to good standards,” he said. ‘I think it’s a gross exaggeration to say the entire Calico Trail is in bad condition and needs to be closed [to motorized use].”

Sensitive terrain

Jimbo Buickerood of the San Juan Citizens Alliance said Calico is one of the trails that became motorized without benefit of a NEPA analysis. “About 15 of these routes have never undergone NEPA,” he said. “The signs just magically changed [to allowing motorized uses]. We thought that would be addressed under travel management, but it wasn’t.”

Marion said he believes it is possible for all types of users to coexist, but that shouldn’t happen above timberline. “The argument I hear is that Calico is the only above-alpine motorcycle trail in Colorado. What I say is, there must be a reason, because every other forest has decided it’s not appropriate to have motorized use up there. The terrain is far too sensitive and the recovery period for damage is so long.”

Johnson agreed. “We don’t think motorcycles belong above timberline or in wetlands. There are plenty of motorized opportunities throughout the San Juan National Forest,.”

Marion, Buickerood and Johnson believe that motorcycles and dirt bikes have exploded in popularity to the extent they are driving out other users who contribute more to the local economy.

“Motorcycle use is now predominant and is driving out other quiet uses in the area,” Johnson said. “We have seen a sharp and distinct trend in increasing numbers of motorcycles and dirt-bikers in the vicinity, and there are major safety concerns.”

Johnson cited the YouTube video as evidence that some motorized users show reckless disregard for the rules, saying the motorcyclist is on a steep, hikers-only trail at the summit of Sockrider Peak.

“It’s not just a few bad apples,” he said. “We see teams of them out there and they’re off-trail.” Last summer, he said, a group of riders was racing on the Calico Trail, wearing bibs and numbers.

The DPLO’s decision on the Rico-West Dolores travel plan did not include an adequate socioeconomic analysis as required by NEPA, Johnson added, and did not view Dunton as a major stakeholder even though the resort pays more than $1.5 million in payroll and property taxes and creates some 50 jobs in Dolores County.

In the San Juan Citizens Alliance’s appeal, Buickerood wrote that “hunters are likely to provide greater economic benefit to the Rico/West Dolores area than motorized trail users on a per-user basis,” citing a statistic from the San Juan National Forest itself that says hunters spend $60 per visitor day vs. $13.29 per visitor day for users of off-highway vehicles.

‘A deep cut’

But a spokesman for motorized recreation said motorized users are being unfairly stigmatized.

Brian Hawthorne is public-lands policy director for the Blue Ribbon Coalition, a nationwide group that advocates for responsible recreation on public lands. The coalition appealed the DPLO’s decision on several bases, one of which was that it had not offered sufficient reason to justify seasonal closures on some trails popular with motorcyclists.

He said the DPLO didn’t tell the public in the proposed travel plan what the closure dates might be, but just announced them in the decision. Upper-elevation trails were designated as open only from June 24 through Sept. 7 annually and lower-elevation trails were to be open June 24 through Oct. 9.

“That [the closures] just came out of the blue in the record of decision,”Hawthorne told the Free Press.

At present there are no seasonal closures except those imposed by nature; the new dates would cut by one-third the typical motorized riding season, Hawthorne said. “That was a pretty deep cut for us.”

Motorcycles and dirt bikes do cause damage, but so do other users, Hawthorne said. “We’re portrayed as, ‘we don’t care, we pollute, we’re noisy, we cause trail damage.’ Well, the facts are in. Humans using trails cause trail damage, whether on a horse or a bike or on foot.”

Hawthorne said he visits Southwest Colorado regularly and is impressed with the work local motorized groups have done to restore trails. “I rarely have been to a place where they have done so much work to minimize resource damage,” he said. “Not every linear inch is up to snuff, but it’s rare to find a trail system where you see new work done every year. I’m very proud of our people.”

While he knows some hunters are bothered by the presence of motorized vehicles, Hawthorne said the hunting community “is a broad and diverse group.”

“About half use motorized when they hunt and the other half hates them,” he said. “But it’s not like there’s no opportunities for primitive hunting up there. It abounds in that region.”

He said he was surprised by the level of “vitriol” expressed about motorized use in public comments. “It was unfortunate that it devolved into what appeared to be a shouting match.”

While the noise created by dirt bikes is a valid issue, Hawthorne admitted, he said new technology such as electric OHVs will soon make that a moot point.

“There’s no reason to be riding a loud bike any more. We have a no-tolerance policy for loud machines in our groups.” He noted that in 2008, Colorado passed a law requiring all ATVs and dirt bikes operating on public lands in the states to meet a sound limit of 96 decibels, except for machines manufactured before 1998.

Hawthorne called for tolerance.

“Motorized people just want to keep what they have open today, keep what’s on the travel map. There’s a couple of user-created routes, sure, so close them. We don’t want those. We accept that we only have to ride on designated trails.”

But he said it’s important to motorized enthusiasts to have some high-elevation trails to ride on in the Rico area. “We were looking at that as being one of the last few areas that is open for us today. We are interested in keeping it open and working with the user groups to fix whatever problems may be occurring.”

Left with the unenviable task of sorting all this out are Beverlin and the DPLO. “I hope the groups on both sides will come to consensus instead of fighting in the courts where nobody really benefits,” he said. “That’s my real hope.

“I think the real issue is if those user groups can seek a compromise within themselves to work with the other people. If they can seek some common ground and get some of what they want and don’t get entrenched in ‘I want everything motorized or non-motorized,’ that’s the trick.”