Park officials say Gavin Smith and his four buddies did everything right in the weeks leading up to their day hike in the Grand Canyon.

But fateful decisions they made after they got there may have cost the 30-year-old his life.

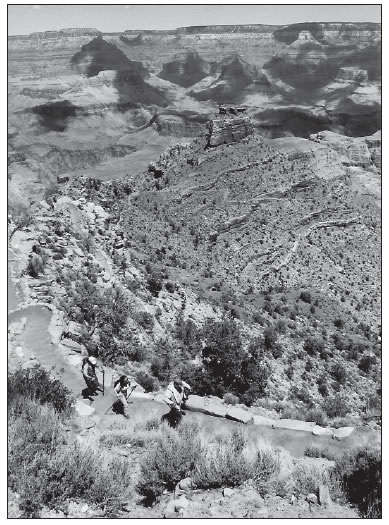

Hikers in the Grand Canyon face a plethora of perils, including heat, sudden storms, and precipitous drop-offs. Death is a constant in the Grand Canyon, and it is often the fittest people who succumb. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

Smith and his friends, who grew up together in Lawrence, Kan., were on what was to be a day hike to the river on the remote Lava Falls Route, near Tuweep in the Toroweap Valley west of Havasu Canyon and accessible from the North Rim. About halfway to the river, Smith decided he shouldn’t push his limits. He’d wait there for his buddies to reach the river and return.

That was about 9 a.m. on Tuesday, Sept. 28, and it was the last time his friends saw him alive. One of his friends found him dead that afternoon, 100 yards from a parking area adjacent to the trailhead.

Smith became either the fourth or fifth accidental death at Grand Canyon this year. Officials aren’t sure whether an earlier falling death was an accident or suicide. Either way, “it’s still within the average of what we see every year,” said Maureen Oltrogge, public affairs officer for Grand Canyon National Park. His death was believed heat-related.

Death is a constant in the Grand Canyon, whether by falling, drowning or succumbing to the extremes – searing heat in the warm months or frigid winds and snowstorms in winter. And Smith’s manner of death has been happening for as long as people have been visiting the place.

“Almost routinely — despite the canyon’s infamous heat, its lack of water, and its lethal cliffs acting as ramparts to imprison the parched hiker away from the river of life flowing within view so far below — hikers underestimate levels of heat and thirst in the Grand Canyon,” wrote Michael Ghiglieri and Tom Myers in their 2001 book “Over the Edge: Death in Grand Canyon.” When the book was written, 65 known deaths had been blamed on environmental factors – usually heat leading to heat stroke or cardiac arrest.

‘It doesn’t take long … ’

In the decade since the book’s publication, the number of deaths in the Grand Canyon has held steady at about 12 a year. Out of that, says Ken Phillips, the park’s chief of emergency services, usually two or three are suicides and a couple are accidental falls. A smaller subset includes drownings, plane crashes and lightning strikes. The largest category – about three or four deaths a year – involves cardiac arrest, which is what generally happens when people die from heat or when they’re not adequately conditioned for the Grand Canyon’s rugged terrain.

Many people are simply unprepared, Oltrogge says. They start down from the Bright Angel trailhead gripping a sports drink in one hand, and that’s all they’ve got. Their shoes may be flimsy. They’re lulled by the easy downhill trail, the extreme beauty and the pull of the river, which is deceptively far away.

The Smith case was different.

“They had done their homework, they had researched the trail, and came prepared,” Oltrogge said. Although the trail isn’t recommended in the hottest times of the year, the group was hiking in September, and probably didn’t expect 100-degree temperatures that were being intensified by the volcanic rock.

Still, Smith’s instincts were technically correct.

“He knew his limitations,” Oltrogge said. “He had nothing to prove. He said he would sit there and wait.” And that’s where the fatality began, because the rest of the group continued to the bottom of the canyon without him.

“The only thing he did wrong was that he was left by himself. It was sad because they tried to do the right thing,” Oltrogge said. “You never want to leave an individual by themselves. Once you start to suffer from the heat, you lose your sense of reason.”

Deaths still happen in larger parties, like the 1990s husband-and-wife team Paul and Karen Stryker, who showed up with too little water for the inner canyon’s searing summer heat – and turned up their noses at lateseason creekbed potholes teeming with life. Later, in their delirium of heat and dehydration, they headed down Cremation Canyon instead of staying on the easy Tonto and South Kaibab trails, their planned route, for one more easy mile to the life-saving river. Paul died, but Karen and her horrific story survived. It leads off the chapter on environmental deaths in Ghiglieri’s and Myers’ book.

Indeed, heading down the Bright Angel Trail is ill-advised for dress-shoes-wearing, out-of-shape folks from other places toting single bottles of beverage. But those aren’t the only people at risk.

Take Margaret Bradley, who in July 2004 died from dehydration during an attempt to run nearly 30 miles on Grand Canyon trails. The 24-year-old marathon runner and medical student got separated from her running buddy when the two ran low on water and made a fateful decision – she would go to the river, and he would hike out.

But she didn’t know the canyon, and was also found dead in Cremation Canyon, where temperatures at that time were estimated at over 120 degrees Fahrenheit.

“This is a tragic reminder that even the most physically fit person can run into trouble in the inner canyon during summer months when temperatures are extreme,” Phillips said at the time.

When it comes to statistics, Margaret Bradley is an outlier by virtue of her gender. The vast majority of people who have died in the Grand Canyon have been males, all but 6 of the 65 people reported dead from environmental factors in Myers’ and Ghiglieri’s 2001 book. Of the people they reported to have died by falling off the rim or from a cliff or steep trail, 71 were male and 17 were female.

Phillips says suicides reveal a gender divide: “I’ve been here 28 years and only two females have thrown themselves off the rim of the canyon. We see several suicides a year.”

But he’s observed – and the numbers confirm – that even the accidental deaths show a marked biological influence.

“It’s definitely younger males that take higher risks than females. It’s a proven fact,” he said. “It has a lot to do with testosterone. Males put themselves at greater risk, attempt things that females wouldn’t normally do, whether it’s swimming in a river, climbing an exposed cliff face or just getting farther out on a promontory.”

Andrew N. Stires is a classic example. A witness told rangers the 42-year-old Burbank, Calif., resident was trying to hop from one outcropping to another on Oct. 1 of this year when he plunged from the South Rim near the visitor’s center. Rangers recovered his body about 500 feet below the rim.

Staying safe

As the Grand Canyon’s longtime spokesperson, Oltrogge has written press releases and participated in interviews about countless deaths. Still, her voice catches with emotion when she talks about them. “Any fatality that we have here is too many,” she says.

Education has become a high priority for Grand Canyon staffers who hope to prevent as many deaths as possible.

Hiking information, including trail conditions and weather, can be obtained on the park’s web site at www.nps.gov/grca/ planyourvisit/backcountry.htm. There’s also a backcountry information hotline at 928- 638-7875, which is answered on weekday afternoons.

Phillips advises hikers to plan as much as possible using those resources, guidebooks and maps before they arrive at the Grand Canyon, and then check in at the Backcountry Information Office.

“They’ll size somebody up,” he says. “They’ve got experience and they can spend time one-on-one with somebody.”

But it’s best not to wait until arriving at the park to book multi-day backpacking trips, he says – because too many people get locked into overly ambitious itineraries when their preferred routes, often the easier ones, are taken. And that’s a recipe for distress.

“Sometimes people get so driven by their itinerary or a goal, getting to the river and back in one day, or if they’re in the canyon and they’ve got a plane to catch. They push on regardless, rather than saying, ‘Hey, I need to adjust my plans,” he said.

Phillips advises people to be willing to scale back their plans to day hikes when necessary, camping in the Grand Canyon Village campground or on Forest Service land outside the park.

“One of the best ways to enjoy it is a day hike,” he said. “Go down partway, come back out. It’s a great way to enjoy the canyon without having all that weight on your shoulders.”

Once you’re inside the Grand Canyon, park officials say, a few key precautions can save lives.

• Stick together, and absolutely avoid leaving a weaker, slower-moving group member behind. Be willing to relieve such a person of some of his weight so he can keep up. In case of injury or other physical trouble, having more than one person on hand leaves someone to hike to a ranger station or signal for help.

• If using a signal mirror, don’t stop signaling until help has arrived.

• Consider toting a satellite phone; cell phones won’t work in most parts of the Grand Canyon.

• Also consider carrying a GPS tracking device such as the SPOT system, which retails for about $150. This allows you to transmit “I’m okay,” “help” or bread-crumbstyle location signals to family or friends who can follow your progress online, or SOS signals to emergency responders.

Phillips did say that SPOT systems have been abused in non-emergency settings more often than they’ve been helpful. One group in 2009 activated their rented SPOT device three times – first because they couldn’t find their water source, and a second time because their water tasted salty.

“The third time we said, ‘Look, you’re coming out,’” Phillips remembers.

He added that the SPOT “is a device that really does work, but people should recognize that it’s an emergency device, reserved for use when you really do have a true emergency.”