Farmington, N.M., artist Timothy David Mayhew lays a narrow box on a table in my office and opens it. As carefully as a jeweler takes a gem from a case, the smallish, broad-shouldered, gray-haired man removes gleaming red, white, and black chalk. He uses it to create studies of North American animals in their environments, returning later to his studio to make the sketches into paintings.

“It’s a dirty job but somebody has to do it.” Humor bubbles in his softly spoken words. “If you want to really do art well, you have to study from nature.”

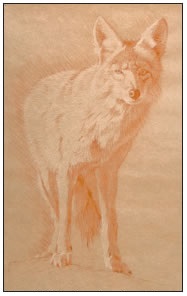

“Frontal Study of a Coyote on Alert,” a drawing in natural red chalk with natural white chalk on handmade paper by New Mexico artist Timothy David Mayhew.

My breath catches as I look at the vibrant chalk before me. Its hues do not belong to some cheap synthetic drawing material from the art department in a chain store, but to rare natural stone dug from the earth, soft enough for the likes of Michelangelo to saw into sticks and use on drawings in the Sistine Chapel. Natural chalk is an ancient medium, dating to Renaissance Italy.

Taking a split reed from his box, Mayhew inserts a chalk stick in one end and presses it lightly on white paper. “That makes the most beautiful black mark.” A smile curving his lips, he extends the chalk to me. It feels cool and hard.

“These materials are much easier to work with than pencil because they don’t smear. They go on with a light touch and stay,” he explains, adding that he can make a drawing outdoors, stick it into a backpack, and take it safely home.

After the Italians started using chalk, the Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) brought it back to Amsterdam after studying in Italy. Artists used chalk until deposits became scare in the 19th Century, and existing mining technology couldn’t retrieve the stone that remained.

Thanks to modern quarries, natural chalk is available once more, but still not easy to get. “The hardest one to find is the natural red, which I think is the most beautiful drawing material that I’ve ever experienced,” says Mayhew, who has located a red-chalk supply in Arizona. His black chalk comes from Normandy, and his white from Dover, England.

“A natural red-chalk drawing will almost jump off the paper at you.” Joy tingeing his voice, he lifts a portfolio off the floor and sets it beside his box.

I lean forward as he opens the cover and displays a red image of a Mexican gray wolf. Intense lines define its paws and nose. “You can make (red) chalk look cooler and warmer just by the way you manipulate it.” He removes a black-and-white drawing of an Alaskan bighorn Dall sheep.

I gasp. Fine sharp lines depict muscles, eye sockets, and the shape of the nostrils. Shadows give the face contour, and the curling horn resembles an etching. Thick fur fluffs along the neck, fading at the shoulder.

Mayhew fell in love with art in his native Michigan because a high-school teacher inspired him. Considering a career as a medical illustrator, he attended both art and medical school. He discovered natural-chalk drawings in the Detroit Institute of Art’s Old Masters Collection.

“They’d just absolutely glow,” he recalls. “I looked around for the materials that created that luster and couldn’t find them.”

Eventually he decided against becoming a medical illustrator, worked as a family practitioner for the Indian Health Service, and began a research project on 15th and 16th Century art techniques. The study included translating manuscripts, some dating to the 1200s. In the British Museum, he discovered a book by Theodore Turquet de Mayerne, a Paris-educated doctor and chemist. De Mayerne mixed paints and varnishes for artists, experimented with pigments, and jotted his findings in Latin, English, and French in the same treatise.

Today Mayhew is a full-time fine artist, and an expert on Old Master materials and techniques. Each April, the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University invites him to hold seminars for staff and graduate students. Last June he gave public and private lectures at the National Gallery of Art.

He combines black and white chalk Renaissance-style. Like Domenico Tiepolo (1727-1804), he uses red chalk on blue paper, or red and white chalk on blue paper. He blends small amounts of red chalk with black chalk in a style called Tocchi di Rosso, Touch of Red; and lets 17th Century Northern European painters inform his composition and use of light.

He makes his own reed chalk-holders. For an extra light touch, he uses feathers to clamp his drawing sticks. “The quills are donated to me by various geese that fly by.”

His drawings are in the permanent collections of museums including the Boston Museum of Fine Arts; the University of New Mexico Museum of Fine Art; the Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque.; the National Museum of Wildlife Art, Jackson Hole, Wyo.; the National Gallery; and the Cheyenne Frontier Days Old West Museum.

Working with natural chalk has affected his attitude toward his drawings. Though he still uses them as studies for paintings, he has gained respect for their value as art.

I glance at a sketch of an alert coyote. Crisp white lines dominate soft red ones. Indeed, the animal seems about to jump off the paper. I would hope Timothy David Mayhew has respect for his art.