First of a two-part series

For two decades, a furor has raged over the fate of a slow-moving stream that meanders through the heart of the Needles District of Canyonlands National Park in Utah.

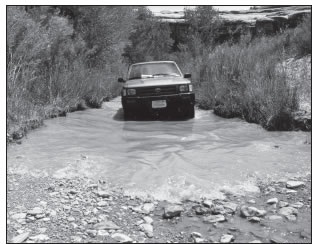

A car traverses the Salt Creek streambed in Canyonlands National Park in the days before motorized travel was banned along the riparian corridor.

The saga has its own distinctive elements, but in many ways it exemplifies the disputes over motorized access now gripping the West.

It even includes an actual instance of a county sheriff defying the federal government and cutting open a gate.

At one time, motor vehicles could rumble southward along the streambed to reach a stunning rock formation called Angel Arch at the far end. Today, that route is closed to motorized travel. Environmental groups and the National Park Service have fought to keep it that way, while San Juan County, Utah, and the State of Utah have battled to have it reopened.

The county alone has spent more than $1 million on the fight, according to one of its county commissioners.

On May 27 of this year, a U.S. district judge issued a landmark ruling that the route did not meet the standards of an historic road under the statute known as RS 2477.

Now, San Juan County and the State of Utah have decided to appeal that decision to the U.S. Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver, meaning the legal battle will continue for years more.

“Once you’ve invested a million, you’d better fight for the result that you want, hadn’t you?” San Juan County commission chair Bruce Adams said in a phone interview.

Far-reaching

Environmentalists, the Park Service, the county and the state don’t agree on much, but they agree on one thing: The case, and the recent ruling in U.S. District Court, could have far-reaching implications.

“It’s a huge decision and I think it’s very significant,” said Liz Thomas, a Moabbased attorney for the nonprofit Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, a key party in the dispute.

In his 81-page ruling, U.S. Senior District Judge Bruce Jenkins found that the county and state had failed to prove that the route had experienced the 10 years of continuous public use that is necessary in Utah to qualify as an RS 2477 road.

“For purposes of R.S. 2477, at least absent proof of continuous public use as a public thoroughfare for the requisite amount of time, a jeep trail on a creek bed with its shifting sands and intermittent floods is a by-way, but not a highway,” Jenkins wrote.

Environmentalists hailed the decision.

In an e-mail to the Free Press, Thomas wrote that, “The Court’s decision is enormously important, not just for Salt Creek, but for the thousands of R.S. 2477 claims on federal public lands across Utah (by some counts, this could be 15,000 to 20,000 claims!).

“The UT Fed. Dist. Court’s decision makes clear that old trails with a sparse history of occasional use by cowboys, prospectors, or off-road vehicle users are not ‘county roads,’ but are federal lands subject to federal control and management,” she wrote.

Adams agrees the ruling was monumental, but takes issue with the outcome.

“We simply think that it’s not appropriate to close the road to Angel Arch,” Adams said. “We think it’s of national significance and everybody, including disabled people, should have the right to enjoy its beauty.

“What the ruling does – it limits the access to those who are physically fit enough to ride a horse or hike 24 miles round trip. We just think that’s wrong and we think the public deserves better and the judge got it wrong.

“The judge in his ruling has almost redefined what Congress and others had defined as an RS 2477 right-of-way.”

Locking the gate

In January 1995, the Park Service adopted a backcountry management plan for Canyonlands that addressed growing concern about the impact of motorized travel on Salt Creek, the only perennial waterway in the park other than the Green and Colorado rivers, which are virtually inaccessible from the Needles District.

Salt Creek, which originates in the Abajo Mountains and runs 32 miles to the Colorado, supports the park’s richest diversity of birds and wildlife outside the river corridors.

“It’s a gorgeous part of the park, very rich in archaeological resources, rich in wildlife,” said Paul Henderson, Park Service spokesman for Canyonlands and Arches national parks. “People have been drawn to that area for thousands of years.”

Prior to the 1995 plan, there were no limits on the number of vehicles that could drive up Salt Creek, according to Henderson. The route didn’t see abundant visitors every day, but over holiday weekends there were upwards of 75 vehicles a day traveling the path, he said, and that caused concern about impacts to water quality, erosion and archaeological resources.

“You don’t have to be much of a biologist to figure out that that many vehicles driving through a stream bed is not a good thing for a healthy riparian zone,” Henderson told the Free Press.

The management plan limited motorized travel to 10 private and two commercial vehicles a day. A gate was installed at the north end of the route and permits were issued to travel beyond that point to Angel Arch. “That seemed to be a good trade-off at the time. The county had never objected to our backcountry management plan. They never really objected to the limits as long as access was available.”

But SUWA objected to any continued vehicle access and filed suit in June 1995 challenging the park’s plan. In 1998, the district court overturned the park’s permit system. The Park Service then installed a second gate on the creek at Peekaboo Spring, a few miles south of the first gate, and locked it.

Motorized advocates take to the streets of Monticello, Utah, in April 2011 to protest road closures on public lands. Photo by David Grant Long

Supporters of motorized access appealed, and in August 2000 the Court of Appeals enjoined the district court’s ruling and remanded the case to the original court for further consideration. The Park Service was also to re-evaluate the impacts of motor vehicles on the creek.

Between 1995 and 1998 “when the court told us to kick the gate shut, there were only a few weekends a year that we did sell out all of those permits,” Henderson said, adding, “I’m not sure that claims that there are thousands of people wanting to drive up there are necessarily true.”

The agency meanwhile kept the gate closed, something that did not sit well with county officials. In December 2000, then- Sheriff Mike Lacy, a deputy, and two other county employees traveled to Peekaboo Spring, removed the lock and chain from the gate, cut the wires, and took down “Road Closed” signs.

The county won that symbolic skirmish, but the legal process continued, and the park did further studies.

“We got a team of a lot of ‘ologists’ and they decided that vehicle use within the corridor was impacting park resources,” Henderson said. In June 2004 the Park Service announced a final rule ending motorized access to Angel Arch.

In July 2004, the county filed suit in U.S. District Court claiming a rightof- way along Salt Creek under R.S. 2477.

The brief statute, adopted in 1866, states, “. . . that the right-of-way for the construction of highways over public lands, not reserved for public uses, is hereby granted.” It was intended to encourage mining and development of the West.

Congress repealed R.S. 2477 in 1976 but said that established roads retained their rights-of-way.

Washed away?

The Salt Creek case went to trial in fall 2009. The county and state provided evidence of what they viewed as continuous use of the Salt Creek route for at least 10 years prior to the establishment of the national park in 1964. San Juan County attorney Shawn Welch argued that continuous public use began with the arrival of a cattleman in the 1890s who moved livestock up the creek. Evidence of use by other ranchers and a cattle company was also provided.

But assistant U.S. attorney Carlie Christensen argued that “sporadic use” did not qualify the road for R.S. 2477 status and said the public still has access to Angel Arch on foot or on bicycle.

Judge Jenkins agreed, writing, “it would strain the language to characterize [the cattle company’s] presence as a ‘public’ use. . .” Scenic tourism via four-wheel-drive vehicles began in the 1950s, the judge wrote, but even then, visitors were “very few and far between.”

Jenkins found that continuous public use of the claimed public thoroughfare had not begun by September 1954, 10 years before the park was created. He ruled in favor of the Interior Department and Park Service, and ordered the county and state to pay the defendants’ costs in the case.

Adams, however, believes the state and county did provide ample evidence to show 10 years of continuous public use. “That creekbed was used by ranchers, farmers, hikers, Boy Scouts, Jeepers – everybody loved to go up Salt Creek to look at Angel Arch.”

Adams said he took his entire family to the arch within a month of the closure because, “I was afraid if I didn’t, my children and grandchildren would never see the Angel Arch.” He has visited the arch numerous times, he said, “but I’ve never hiked the 24 miles and I don’t intend to,” although he might ride a horse.

The only other way to Angel Arch is via Cathedral Butte to the south, and that involves a long hike down a very steep canyon, he said. “That’s even more limiting than the Salt Creek route.”

He said any damage done by motor vehicles is soon eradicated by nature. “Every time it rains, all the traces of man are washed away.”

But SUWA’s Thomas disagrees.

“I would say that perhaps the tire tracks are washed away,” she said by phone from Moab. “Vehicles make ruts and when there’s a big flood event the path of least resistance is through the ruts because they’re linear and going downstream. It creates immense erosion that would not be there if it were a healthy floodplain.”

Supporting wildlife

Today, the route remains closed to motor vehicles pending the outcome of the latest court battle.

“Nothing has changed on the ground,” said Henderson. “We closed Upper Salt Creek to motor vehicles in June 1998 when the courts ordered us to do that, and this thing has been in court ever since. It has been a long weird path to where we are at.”

Thomas, who has made the hike to Angel Arch, said Salt Creek today is beautiful, with “tons of vegetation.”

She said research she did regarding Arch Canyon, a BLM-owned riparian area in San Juan County where motorized use is also an issue, showed that riparian areas make up less than 1 percent of the total BLM land mass in Utah and yet support 75 to 80 percent of all wildlife. “I can’t imagine it’s different for Park Service land,” she said.

Henderson said there are places in Upper Salt Creek where one can no longer tell there were ever tire tracks. “The recovery truly has been amazing,” he said.

Henderson said the Park Service doesn’t keep track of day users in Salt Creek but issues permits for backcountry camping. During the prime hiking season (spring and fall) the backcountry sites in Salt Creek are booked months in advance. “They’re among the most popular places in the park.”

But, he noted, “There’s certainly a segment of the population that hates the fact that they can’t drive up there and feel they’ve been denied access.”

Creating criminals

That segment includes most of San Juan County, according to Adams. He said the commissioners’ decision to appeal was unanimous and he believes the vast majority of the county agrees as well. Access is a huge issue in San Juan County, he said.

“We’re not only pursuing the RS 2477 claim on that road, but there are many, many other roads that we’re claiming as RS 2477.” The county has been advertising for members of the public to come forth with concrete evidence of the use of any road in the county prior to 1976. “We think it’s in the best interests of the public at large to have open access.”

Adams said there are more ATV riders in the nation now than ever before and “you can’t say every place in the world is off-limits to ATVs. Then you start making criminals out of your constituency because they want to ride.”

Thomas, however, said in San Juan County there are some 5,000 miles of designated motorized routes on BLM land alone. “There’s plenty of places for people to drive vehicles.”

Worth fighting for

Even if the county ultimately wins the Salt Creek battle, it would gain only a narrow right-of-way through a national park. But Adams said the access is worth fighting for because of the precedent the case will set for other RS 2477 claims.

“I’m sure the other side looks at it the same way,” he said. “How many roads is the county going to spend $1 million on to fight to assert its position? We felt this case was as winnable as any we had in the county. If we could win this one we think that would set a precedent for us as well as other counties.”

The Park Service’s Henderson, who was in his position in June 1998 when the road was closed and has watched the various decisions, said he is not surprised that the county would appeal.

“It’s because this is such an issue throughout Utah and certainly some places in Colorado,” he said.

“If this decision were to stand and become the new case law, there’s parts of it I feel do put the onus of proving what is a right-of-way on the county or the political subdivision making that claim.”

The case is important to the park as well, he said.

“For Canyonlands National Park it certainly is. If the decision stands, it would put to bed the notion that someone other than the public of the United States has either a right-of-way or a title claim to any of the land in Salt Creek. I think from our perspective it just allows us to continue the management in the Salt Creek corridor we’ve had in place since 1998. For us, we just won’t have to be spending quite so much time preparing for court cases!”

Next month: The controversies and legalities surrounding some other RS 2477 claims in the region.