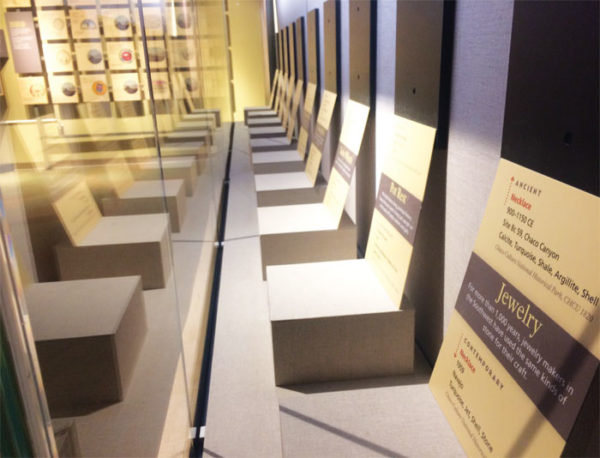

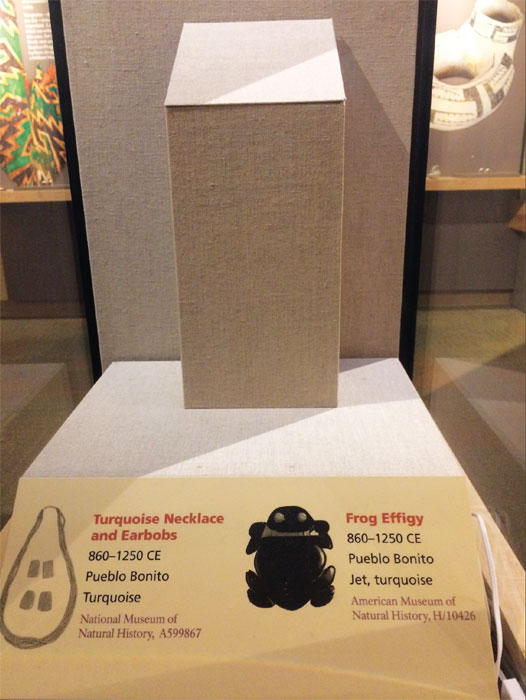

Behind a closed door inside a new $2 million visitor center at Chaco Culture National Historical Park sits a room full of informational signs, empty display cases, mounts, and lights. People who ask about the mysterious exhibit are allowed inside, according to the park’s public information officer, but the room holds no artifacts of interest – no secrets of the past.

During the 1100s, the dwellings that are now part of the park in northern New Mexico housed what would become some of the most valuable cultural objects ever found in the American Southwest. Pottery, musical instruments, gems, copper bells – even skeletons of macaws brought from central America filled the rooms.

“It was sort of like Fort Knox and the Metropolitan Museum all in one,” said former Chaco Superintendent Barbara West. She said a professor from the University of Virginia told her that more turquoise had been found in one room in Pueblo Bonito than in the entire rest of the American Southwest combined.

But when archaeologists in the late 1800s and early 1900s excavated the sites, they took most of those priceless artifacts back to their home institutions on the East Coast.

“It had been plundered by the museums,” West said. “Visitors would come in and ask, ‘Where’s all the stuff ?’ It was hard to tell them that it was in New York and D.C.”

Many of the most valuable artifacts excavated from Chaco now rest in storage cabinets and drawers at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Smithsonian Institution and National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. Over 2,000 miles away, when visitors tour Chaco’s ancient buildings, they see only the empty rooms. And though Chaco displays a collection of some artifacts and specimens collected from excavations in the 1970s and 1980s, the majority still live in storage.

Today – despite a years-long effort to return some of the most extraordinary artifacts back to Chaco and house them in a state-of-the-art facility for visitors and the descendants of Chaco’s inhabitants to see – those artifacts may remain in the cabinets and drawers on the East Coast indefinitely.

Meanwhile, the mostly-finished exhibit room sits vacant in Chaco’s new visitor center, rendered unusable by a faulty heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) system. Behind the whole building lies a set of conflicting accounts about what is happening and why the problems are so hard to fix. The Free Press spoke with present and former employees to try to understand how the story got to where it is today.

The plan

When West arrived as superintendent of Chaco in 2005, its 1950s-era visitor center was in bad shape. In an interview with the Free Press, she explained the building had a leaking roof, electrical problems, and serious structural defects. It wasn’t hard to convince the National Park Service to fund a replacement for the visitor center, but the park’s artifact exhibits would likely have to remain in a wing of the old center, which had been remodeled in the late 1990s. The rest was to be rehabilitated as office space.

However, when crews began the renovation, they found even more defects, said West. She said she worried that even though visitors might eventually have a new visitor center, the only exhibits they would see would still be housed in a deteriorating building.

So she applied for more funding from the Park Service’s regional offices, wrote project proposals, and almost two years later, convinced the Park Service to fund a special exhibit space to be housed in the new visitor center.

The old center was torn down at the end of 2010, and in 2011 construction began on the new visitor center, according to a park web page from 2012. The visitor center would soon open to the public, but the special exhibit space would need more careful planning.

Dabney Ford was Chaco’s chief archaeologist at the time. She told the Free Press that she, West, the park’s curator, and the park’s chief of interpretation had started planning the exhibition about five years before its planned installation. They reached out to the East Coast museums that held the artifacts to negotiate loan agreements, and traveled to New York and Washington, D.C., to choose which items to put on display.

Ford said they wanted to show artifacts that represented “the high level of artistic, scientific, and technological advancement the people at Chaco had reached,” rather than items from simple, day-to-day Chacoan life. They consulted with members of the 21 modern Pueblos to decide which artifacts would be culturally appropriate to display to the public. Ford said apart from some elders, few of the Pueblo people even knew the priceless artifacts existed. “They were just blown away,” she said.

Ford also explained that park law enforcement, maintenance, and curatorial staff worked together to make sure the exhibit hall was designed to properly hold the artifacts. They added security features, including cameras and intrusion alarms that would sound in multiple places, even the chief ranger’s house. They made sure there were no windows, and that water pipes didn’t go near the display cases. The entire space was designed to adhere to the standards of both the Park Service and the lending institutions — on par with museums in big cities.

The process continued after Ford retired in February 2016. Chaco staff worked with exhibit and preservation experts in Harper’s Ferry, W.Va., where the Park Service designs and creates its museum materials. They designed floor plans, interpretive signs, display cases, and podiums for the exhibits. Staff, along with interns and university archaeologists, carefully inspected each artifact chosen for display to make sure it was ready. They gave each one special mounts, felt bases, and tiny fasteners to hold it upright — even painting the fasteners to match the color of the object.

Teams also made detailed preparations to ship the artifacts to Chaco — a process called conservation, which involves assessing each article’s readiness to travel, filing extensive paperwork, and building cases to hold the artifacts during travel.

The exhibit space was almost ready for the artifacts, but there was one huge problem. The room’s heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning system kept malfunctioning. Though the visitor center portion of the building remained comfortable, temperatures in the exhibit room would swing wildly from one extreme to the other, and humidity levels would fluctuate unpredictably.

One winter day, the space was a chilly 39 degrees, according to a January 2017 article in the Santa Fe Reporter. During the summer, a former park volunteer recalled propping a fan between the visitor center and a door to the sweltering exhibit room to balance out the temperatures.

The conditions were not at all acceptable to hold the delicate and perishable artifacts, some of which are made of wood or textiles that could easily deteriorate such conditions. They require extremely precise sets of humidity and temperature to meet Park Service – and lending-institution – standards. And the current system is still nowhere close to meeting those conditions.

The problems

Exactly what is wrong with the HVAC system, and why it is so hard to fix, are difficult questions to answer. West and her two successors give differing accounts.

West retired from Chaco in January 2013 — shortly after the visitor center had opened to the public, but long before the exhibit area was finished. That section was still in its planning phase, she said, but it had a detailed plan that been shared with the Park Service and approved by the regional office.

West echoed Ford’s account of the security and preservation features that park staff had requested for the exhibit. But she said she had no idea that something was wrong until she spoke with a member of the staff last spring, who explained the HVAC problems. “Everything was working fine when I left,” she said. “So someone didn’t do something right.”

After West retired, Larry Turk, then superintendent of Aztec Ruins National Monument northeast of Farmington, N.M., became superintendent of Chaco, in addition to his duties at Aztec.

“When I got on board, we started looking at the exhibit hall closer,” Turk told the Free Press. “That’s when we realized we would need a more controlled environment for the exhibit, and a stand-alone HVAC system.”

He said his time at Chaco was mostly spent on constructing and installing the exhibit, and the HVAC system hadn’t been completed by the time he left. The heating and cooling system’s was installed at the same time that other parts of the exhibit were being constructed. Turk said any specific information on plans was the responsibility of the contractors and the employees at the regional office who managed them. He said some improvements were made, and plans were developed for a backup generator that would power the building in case of power outages.

When asked if he noticed any problems during construction, Turk said there were a few, but they were minor.

“We ran into snags, just like you do in any project,” he said. “But by the time I left there, I was unaware of any major issues.” He said he thought all had been going according to plan after he left, and seemed surprised to hear that there were major HVAC issues.

Turk left Chaco in June 2016, and became superintendent of four National Historic Sites in New York. During his interview with the Free Press, he emphasized repeatedly that he was no longer speaking for Chaco. He said he had had very little contact with Chaco’s new superintendent, Michael Quijano-West (no relation to Barbara West), after his move.

Turk mentioned one single phone conversation, shortly after Quijano- West arrived, when HVAC issues did come up.

“I just told him what I knew,” Turk said, but he couldn’t remember specifics because the conversation had included other construction questions as well. “I thought it had been going according to what had been planned,” Turk said.

But Quijano-West said when he arrived at Chaco in November 2016, there were already problems with the HVAC system.

“There’s a long history of things, and I’m not acquainted with all the time periods and issues that have been happening,” he told the Free Press.

Climate extremes

In Quijano-West’s eyes, the main problem was not the HVAC system itself, but the park’s isolated location, extreme climate, and drastic temperature and humidity fluctuations. The high concentration of minerals in the water supply also makes it difficult for machines to control humidity, he said. Another major problem is the frequent blackouts and brownouts of the park’s electrical infrastructure. The power fluctuations reset the HVAC system’s computers and erase data, and specially-trained operators from Santa Fe or Albuquerque are needed to correct the problem. “Even our IT people can’t tweak HVAC systems,” Quijano-West said.

Moreover, the park’s facilities are located at the end of a 20-mile gravel road and more than 150 miles from any city, so it can take hours or sometimes days for help to arrive.

He stated that the HVAC system had already been replaced twice, information neither previous superintendent had shared. He also indicated that the exhibit hall and visitor center may not have been planned adequately in the first place.

“I don’t know if [the previous superintendents] were assessing what the capabilities on the ground were,” he said. “Employees have expressed to me that there had been problems in this building since it was built.” (Chaco’s public information officer and chief of interpretation, Nathan Hatfield, also agreed that the exhibit’s system had had problems since he had arrived in September 2015.)

But Quijano-West could not point to any specific problems with the system besides power issues and the isolated environment. No one within the park was trained in the system’s operation. He said only the off-site contractors were fully aware of its issues. And he would not identify those contractors, citing regulations requiring contractors to work only with the regional office. Having a reporter speak directly with a contractor might interfere with the contract agreement, he said.

After repeated questioning, he agreed to forward any specific questions about the HVAC system to the regional officer via email, but could not guarantee a timely response.

No opening date

The superintendent was also unclear about when the exhibit might open. He said the park had ordered a new backup generator, and experts were making specific adjustments to the HVAC controls. He expected the installation process to take about 45 days, but even if the system could be fixed, he explained, it must go through a long test period to make sure the temperatures and humidity are fully stable. He did not say exactly how long that would take, but said it could be a few seasons – enough to monitor the changing environmental conditions of the park. Once that test period concludes, then the system may meet Park Service – and eventually lending-institution – standards.

Few visitors are likely to know the exhibit exists. According to the park’s website, “the museum in the Visitor Center is under construction and is expected to be completed in the spring of 2017.” Though there were two public meetings held about the exhibit earlier this year, only one newspaper has written about it during the past year. More information may eventually become available; Hatfield and Quijano-West confirmed two Freedom of Information Act requests from media organizations related to the exhibit. They refused to provide details.

The exhibit’s total financial costs are still unclear. According to Quijano-West, the visitor center cost about $2 million to construct. But he refused to give estimates on the cost of the exhibit itself. West also said she had no idea on the exhibit’s total cost, and Ford wouldn’t speculate either.

Exact numbers likely lie deep within Park Service budget documents, building plans, and contractor invoices. The total cost of the exhibit may not be known until years after it opens – if ever.

Larger issues

Both Ford and West said the exhibit’s problems represent broader problems with Chaco’s management. They pointed to the decision by upper-level Park Service officials to consolidate management of the Aztec and Chaco units, which allowed park managers to live almost 70 miles away in the town of Aztec. “There’s just a lack of [employee] presence, and that affects interest in getting the exhibit done,” Ford said.

Furthermore, Ford hinted at communication gaps during the transition between Turk and Quijano-West. She said that “little had happened” by the time Quijano-West arrived, though she wasn’t specific about issues during Turk’s tenure. Quijano-West “did walk into a bit of a mess,” she said, “but I think he was not really aware of the amount of planning and the number of consultations we had…A lot of the decisions that had been made [by administrators] may have been based on a lack of understanding.”

In response, Quijano-West flatly denied that the new management structure had any effect on the exhibit’s problems. “I managed two parks [Salem Maritime and Saugus Ironworks in Massachusetts] before I came here,” he said. “I could see some of our older staff thinking that’s problematic, but with computers, cell phones, and multiple ways to communicate, that has helped.” But he did say that he has had very little contact with the people who planned the building.

“They’re all retired,” he said.

At the end of the day, Ford says the exhibit’s problems affect visitors the most. “If the public knew how much had been invested, and how close we were to being finished, I don’t think they’d be happy at all, ” she said.

But Quijano-West says there’s a larger problem. “This kind of an exhibit should have never been created to begin with,” he told the Santa Fe Reporter in January. “It’s unrealistic to expect us to do a New York City-style exhibit here.”

Today, as the seasons change and the park moves toward winter, the exhibit space will likely remain empty. While temperatures inside Pueblo Bonito drop into the teens and 20s, artifacts that once lived in the 800-year-old building will remain in boxes and drawers inside modern, temperature-controlled rooms 2,000 miles away. They will be out of sight of the public – and of the descendants of the ancient people who created them. But they will be safe from a faulty HVAC system – as well as the harsh climate of Chaco Canyon.