Katrina Blair has known for most of her life that she’s called to live and work with plants.

“When I was a little girl, I was floating on Haviland Lake, and there were all these plants on the shore that were calling me over,” she remembers. Her brother and cousins paddled to a nearby beach to eat lunch, but Blair, then aged 11, paddled to the other side of the lake to heed the plants’ beckoning. “I got euphoric when I sat down. They said, ‘Oh, you’re home. You’re going to live your life with us.’”

Fast-forward two decades, and Blair’s passion has led to an undergraduate degree in biology, a master’s degree in holistic health, and a plant-centered organization in Durango called Turtle Lake Refuge. She and a consistent crew of volunteers grow, gather and serve all manner of plants. They dry weeds in solar dehydrators and grind them into powder for winter smoothies. They harvest acorns for acorn ice cream, Oregon grape berries for granola and wild pigweed (amaranth) seeds for crackers. The fruits of their labors supply bulk bins in stores, a booth at the local farmers’ market, schools and restaurants, year-round.

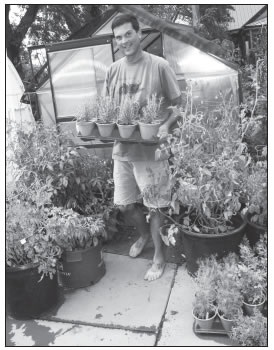

Matt Keefauver of Cortez, who is very active in the local-foods movement, spent a year eating nothing that had been produced outside a 200-mile radius of his home. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

It may sound like a lot, but Turtle Lake’s activities represent just one portion of a flourishing local-foods scene. The refuge is part of Growing Partners of Southwest Colorado, with a mission to implement sustainable local-food programs for all incomes, ages and cultures. Other member organizations include the Southern Ute Community Action Program, La Boca Center for Sustainability and the Garden Project of Southwest Colorado, which helps schools and organizations start or enhance garden programs.

Many of La Plata County’s local businesses number among — or helped establish — the Local First collaboration, which advocates for locally owned businesses of all types, including local farmers and several local restaurants, such as Zia Taqueria and the Cyprus Café, which serve local foods.

Both Durango and Cortez boast thriving farmers’ markets during the growing season, late spring into fall. Durango’s is from 8 a.m. to noon on Saturdays in the parking lot of First National Bank, 259 W. 9th Street, and Cortez’s takes place at 7:30 a.m. on Saturdays in the Montezuma County Courthouse parking lot. There are smaller farmers’ markets in Mancos, Dolores, and Monticello, Utah.

Local produce is so plentiful, in fact, that Cortez City Council Member Matt Keefauver spent a year between the spring of 2008 and the spring of 2009 eating nothing — or almost nothing — that was produced outside a 200-mile radius of home. He doubled the size of his home garden, maintained 25 chickens, worked in exchange for veggies from Stone Free Farm in Montezuma County, ate goat cheese from a friend’s herd and procured wheat flour from the Cortez Milling Company, two blocks from his house. The 200-mile range allowed him to get fresh fruit from the Front Range and his staple grain, quinoa, from the San Luis Valley.

Keefauver said he did it partly to support local growers, many of whom he’d gotten to know by taking the products of his own business, Tierra Madre Herbs, to the Durango and Cortez farmers’ markets.

“The idea of local foods is way more about community than anything else,” he says. “It’s about making a connection with people who grow the food.”

And it’s about the environment; he’s trying to reduce the carbon footprint of his diet. On that point, Keefauver sees a practical side.

“Some day it’s just going to be more expensive to ship food across the country than it is now,” he said. “Our whole system is based on cheap oil. Some day that system is going to fall apart, and we’re going to need to rely on our local food systems.”

Rebecca Schild, the Environmental Center coordinator at Fort Lewis College, said the Durango area experiences a fairly short growing season with frosty nights lasting into early May and resuming as early as September. Both Durango and Cortez are at 6,500 feet, near enough to the San Juan and La Plata mountains that some mountain weather offsets their aridity. A thriving demonstration garden at Fort Lewis uses a greenhouse to get plants started before it’s warm enough to transfer them outside.

Schild says the whole five-county region — which includes Archuleta, Dolores, La Plata, Montezuma, and San Juan counties – has a rich agricultural history, but like Keefauver, she believes the emphasis on local foods entails a modern- day urgency.

“We are pretty vulnerable to energy issues and climate change,” she said. “I think people see local foods as a way to insulate us, to bring the community together again, and to make us resilient.”

For Turtle Lake’s Blair, that resiliency matters even at the level of the individual.

“I think people really are feeling the need to get re-empowered around their health,” she said. She uses the example of cancer, where options at a hospital — chemotherapy and radiation — are limited and fairly grim.

“Truly the options are vast when you turn to local and wild foods,” she says.

Blair believes cancers, like most human diseases, exist in acidic body chemistry. “When you start shifting toward more fresh greens and fruits, the chemistry of your body switches to the alkaline side and the cancer can no longer thrive in that condition. When you realize you can go out into your back yard and eat dandelions and have a shift, that’s empowering.”