“This is bulls–t!” declared one disgruntled Bluff homeowner at a public hearing in May. But, in actuality, it was the ultimate disposition of human waste that was under discussion during the lively meeting of the Bluff Area Service Board.

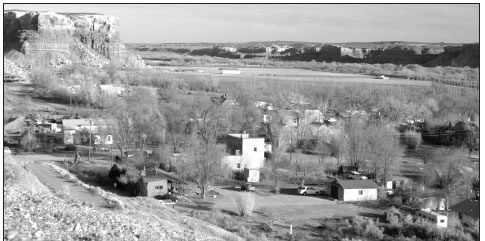

The small town of Bluff, Utah, has struggled for years to decide whether it needs a centralized sewer system, and if so, what type. Recently the Bluff Service Area Board selected a small-pipe system, but their decision is not embraced by everyone. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga.

“We don’t have to put in a $2 million [sewage] system because we got some wells that people aren’t even using for drinking water anyway,” she said. She and several others who attended the May 14 meeting were strenuously objecting to a plan for a new public sewage system under consideration by the board.

The critics questioned the cost as well as the necessity and reliability of the proposal — a hybrid arrangement that would require new septic tanks at most homes and businesses as well as a “small-pipe” network that would gather the digested effluent, further process it through a series of filtering tanks and then pump it up to the highest spot in town. From there it would be used to supply a drip irrigation system to water trees and park lands as it makes its way back down the slopes of the tiny village through the soil.

Actually, the cost of the system has been estimated at nearly $5 million, including the drip irrigation system and the annual operating and maintenance expenses. The funding would come mostly from grants, but would also require a loan of around $1 million, or about 20 percent of the total. Residents would be assessed a monthly fee, currently estimated at $26 per ERU (equivalency residential unit, or 4,000 gallons per month) for the service, regardless of their actual usage or the size of their houses.

Still, a few business owners at the meeting maintained their fees would be so much higher the additional cost could bankrupt them, because their potable water consumption would be metered and they would be charged on that basis — $26 for each 4,000 gallons used, which could get fairly pricey for restaurants, motels and especially RV parks, where guests often fill the water tanks of their motorized behemoths, which can hold several hundred gallons.

The controversy over what to do about Bluff’s sewage has dragged on for several years. Residents now rely on individual septic tanks with leach fields, but health officials have found a higher-than-normal rate of failure among those systems, and have expressed concern that the runoff may be polluting the aquifer that supplies potable water to the town through numerous wells.

“The wells must be protected,” declared service-area board member Skip Meier, explaining that state and federal law require that leach fields be a certain distance from wells and this often isn’t the case in Bluff, especially in some areas of town with small lots. “Eliminating these leach fields is the main goal, the main requirement and purpose of having a public wastewater system.”

But some critics have argued that the proposed system is relatively new and untried, and it would be far more reliable to simply install a traditional, centralized system — something vehemently opposed by many others in Bluff.

Meier said the advantages of the proposed sewage system over a more traditional “large-pipe” centralized sewage plant include having fewer moving parts — only 10 or so small pumps to get the liquid effluent over any uphill portions of the system to the filtering tanks, and a pump to get the treated water to the higher points of the drip irrigation system.

But mostly it would rely on gravity, he explained, and the pipes that collect the liquid runoff from the septic tanks would be much easier and cheaper to install than the sewer mains a centralized system would require to handle solid waste.

“There’s very little maintenance of this system whatsoever except looking at it and, if a pump goes bad, replacing it,” he said, with the pumps having a life expectancy of seven to 10 years and costing about $600 each. “We’ve found a lot of other places in the United States and other parts of the world where this type of system has been in use for many years and has worked — it is not something that is unknown and untried,” he said. “It has been working elsewhere and working quite well.”

‘Exorbitant and unrealistic’

One of the proposal’s harshest critics is San Juan County Commissioner Lynn Stevens, who accused the Bluff Service Area Board of painting a far-too-rosy scenario of its efficacy, penalizing business owners, and ignoring the benefits of a centralized sewer plant/lagoon system, including an offer by local rancher Park Guymon to provide free land for that alternative.

“I think they’ve got the billing process backwards and picked the wrong solution,” Stevens said during a phone interview with the Free Press. Under the proposed user-fee structure, businesses would pay about two-thirds of the cost for operating and maintaining the system, while residential fees would be fixed at $26 a month regardless of how much effluent they added to the load.

A centralized sewage-treatment plant “offers a lot less lifetime maintenance,” Stevens said, “and it’s certainly far more adaptable for expansion and growth, even though I realize the governing voices of the Bluff Service Area are not in any way interested in growth. Now that they’re [living] there, they basically don’t want to see anyone else come [to Bluff].” Stevens did not attend the May 14 public meeting, but some business owners also expressed concern that if the number of residential users declines, the cost for commercial users will increase.

“I think they’ve got it backwards,” Stevens said of the fee structure. “In most areas, large businesses are given rate breaks, but it’s my understanding that Bluff Service Area intends to give the rate breaks to the households and charge the businesses more.”

Stevens said in addition to donating the land for the plant and wastewater lagoon, Guymon had even offered to dig the trench to install the system.

“[The BSA board] just shut him down — didn’t even want to hear him speak at all in that meeting,” Stevens said. “In my opinion, they’ve given exorbitant and unrealistic [cost estimates] associated with the lagoon to make it look bad and they’ve grossly understated the real cost that’s going to happen with this small-pipe drip-permeation system — the life-cycle costs and continuous maintenance.

“I’m not sure that they have the facts to really make that decision.”

The county commission has no authority to overrule any actions of the service-area board, which is an independent entity created to provide services to the Bluff area, which is unincorporated, Stevens explained.

“However, they will need support documentation from the county commission if they’re going to get funding from the state Community Impact Board,” he explained. “They can pick any kind of system they think is best for them, but I both personally and officially think it’s the wrong answer.”

Stevens said he questioned whether the board would be successful in obtaining funds. “I am very skeptical that they will. I think the [funding agencies] are not going to believe their figures and their story.

“[The board members] have gone out of their way repeatedly to make it clear how the county commission has nothing to do with what they say, but then when it comes to a requirement for support from the commission for backing funding, they want to be friendly.”

He said he is also concerned about potential liability if the county endorses the system and Bluff proves unable to repay the loans.

‘Most intelligent’

At the meeting, Bluff resident Jim Hardin, head of operations for the town water system, challenged state engineer Doug Mize’s generous estimate of the proposed system’s durability, including the life expectancy of the filters and the drip dispersal system, saying, “That’s not what the University of Utah says.”

Mize said he and other state officials had spent “countless hours” deliberating on what system would work best for Bluff regardless of what others’ views might be.

“Truly, some of the most intelligent people I know I have the pleasure to work with,” Mize said. “If we’re going to invest $4 million in Bluff, Utah, we want to make absolutely sure it works.” He said answers to questions such as how long particular filter media would last depended on the actual system chosen in the design phase of the process.

“So I appreciate Jim’s comment,” Mize said, “but we haven’t even selected the type of treatment yet,” with options including fabric filters that need replacing fairly often, or a gravel medium, which has a life expectancy of at least 20 years.

“That’s what we’re proposing for Bluff,” he said. “That’s what the engineer recommended and that’s what the state concurs with.”

One woman asked about the possible effect of various chemicals that function as endocrine disruptors, altering human and animal reproductive systems. Such substances, which among other things can come from hormones excreted by women taking the Pill, are present in treated sewage effluent.

David Ariotti, district engineer with the Utah Department of Environmental Quality, said the EPA currently has no standard for endrocrine disruptors, but that most are broken down when the effluent is dispersed in the soil, although some are more persistent.

“I don’t want to add any fuel to any fire, but the higher the retention time, the better the endocrine disruptors are broken down,” Ariotti said. “But for a community the size of Bluff, even discharging directly into the San Juan River, is there a pollution effect? No.”

Also, he said, the harmful effects of endocrine disruptors are mostly based on studies on aquatic species, which is why it’s difficult for the EPA to come up with guidelines.

“They’re working on it, but we have no direction, so we’re just going to have to go in-house with what we feel is best, but we do feel the selected alternative does address that issue.”

Affordability

Service-area board member Dudley Beck said one of the board’s big concerns about any system that didn’t return water back to the town was the effect that eliminating leach fields and containing the effluent would have on the multitude of trees gracing the town. He noted that old pictures of Bluff show a noticeable absence of such greenery.

“If you go back to pictures of Bluff around 1910, there were no trees,” he said, explaining that water from leach fields created since that time, about 15 million gallons a year, had allowed them to thrive.

“This system will allow that water to continue to sustain those trees,” he said, explaining that the dispersal system would require about 10 acres of land at various locations around town to introduce the treated water back into the ground, with some of it in the higher elevations in the northeast portion.

But not everyone embraced the idea of the new system.

Galen Headley, owner of the Coral Sands RV park, said his accountant informed him that his cost would be nearly $1,300 a month and this, along with other overhead, would bankrupt him in short order. (That would amount to water usage of about 200,000 gallons monthly, based on the ERU formula.)

“There’s no way Coral Sands is going to generate that,” Headley said. “There’s just too much overhead on top of that.”

Beck said the board was concerned about Headley’s situation in particular, and suggested they may be able to cut a deal and purchase some of his land as one site for the dispersal system.

Beck said he was “glad [the issue of affordability] is on the table and we need to keep having dialogue about it.

“It is obviously true that if our commercial businesses can’t survive we can’t do this project, so it’s in all of our interest to help in whatever way we can.””

Beck also pointed out that a new sewage system would also help protect the San Juan River, which is very popular for boating and rafting, and is a big part of the local economy.

In a phone interview, Meier told the Free Press that the service-area board had voted in favor of the decentralized system at its May 21 meeting and has applied for grant money to complete the design phase, which will develop a detailed plan, or possibly fund both the design and construction of the system.

He said the goal was to fund 80 percent of the total cost through grants from government entities and obtain a loan for the remaining 20 percent. He said the estimated revenue from the ERU fees would be about $90,000 annually, which would be used for operation and maintenance, loan repayment and establishing a reserve fund for unexpected expenses. About a third of that would be generated from residential fees and two-thirds from businesses, based on estimates of their current usage, he said.