|

Related story |

Grand Canyon National Park, Ariz. — The California condor, a giant vulture once on the brink of extinction, can be seen enjoying a measured comeback here, soaring above the deep canyons and nesting in caves along towering cliff faces.

But recently, lead poisoning from hunting has threatened the condor’s survival, prompting a successful alliance between wildlife conservationists, hunters and ranchers to solve the problem and help save the endangered bird.

Sixty-two condors are now flying over Vermilion Cliffs National Monument in Arizona, the Kaibab Plateau and the deep gorges of Grand Canyon National Park. The boisterous birds, a prehistoric species dating back to the Pleistocene Era, have successfully reproduced on their own under a breeding and reintroduction program run by the Peregrine Fund.

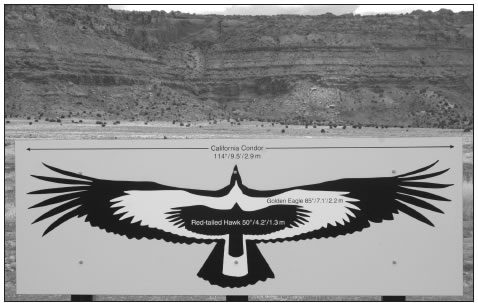

A sign at the Vermillion Cliffs in Arizon shows the comparative sizes of ravens, golden eagles, and California condors. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga.

“They are doing very well. We have four active nests right now and we had two young produced last year, so that brings us to a total of seven born in the wild,” said Chris Parish, the Peregrine Fund’s director for the condor reintroduction program.

“We’ve answered the questions about whether they can rebound on their own. Now we are getting down to the nitty-gritty and addressing their leading cause of death and that is lead poisoning.”

Carrion buffet

It turns out that the California condor, North America’s largest flying land bird, is at severe risk of lead poisoning from ingesting carrion left from seasonal hunting on the vast Kaibab Plateau.

There is a unique relationship between big-game hunters and the scavenging condor that has simultaneously helped to save the bird while also poisoning it.

“Hunting season is a wonderful opportunity because it provides a great food source – gut piles and carcasses — for the condor during wintertime,” Parish explained.

“Breeding season begins in December, which is odd because it is one of the toughest times of year for them to find food, so the relationship with the hunter could not be better for the condor because they are well-fed during that important time.”

But since 1996, when condors were first released from the Vermilion Cliffs, a team of biologists closely monitoring the growing flock learned that this symbiotic partnership has led to deaths as well. Left unchecked, they realized it could wipe out the species completely in the Southwest within a few years.

Between 500 and 700 deer are killed annually on the Kaibab, according to the Arizona Department of Game and Fish, most during a one-month period during the height of the hunting season. Fragments of lead bullets left behind in gut piles and deer carcasses, the condor’s favorite local food, killed seven birds in recent years, threatening to reverse the success of the reintroduction program.

“One carcass can poison up to 15 birds because they are so social when they are doing their job of cleaning up,” explained Marti Jenkins, a field biologist with the Peregrine Fund, during a recent tour.

Hundreds of lead fragments remain in carcasses and gut piles even when the bullet goes through, she said.

Facing the needle

The birds require intense management to avoid a severe die-off, Jenkins said. And that involves luring birds to the release site atop the Vermilion Cliffs using donated cow carcasses and capturing them to test for lead poisoning. If needed, and it frequently is, a treatment process called chelating is administered where calcium is injected into the bird to replace the lead building up in its bones.

“It’s a painful and traumatizing process for them because the calcium is injected subcutaneously into the leg,” Jenkins said. “Some of them seem to mope around once they realize it is their turn. Others fight hard when we hold them down. I’ve got the scars to prove it!”

The treatment is given twice a day for five days; then the patient is cut loose again. At times, there are 18 birds in a specially designed barn receiving chelation, she said. Without it the condors would not survive.

“If we stopped this intense management we would lose an enormous population within one year.”

The birds, which can weigh up to 30 pounds, are not necessarily more susceptible to lead poisoning than other birds, Parish said. Rather, they are surviving on carcasses contaminated with lead ammo.

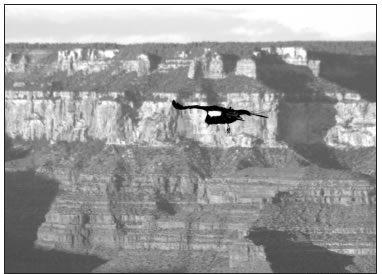

A condor flies in the Grand Canyon in Arizona, where the giant birds can commonly be seen. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga.

Preventing the lead from entering their system is the key to a more sustainable population, plus it keeps the dreaded needles away.

“They are very good at surviving and reproducing on their own without intervention, so without the lead in the environment we could go home,” Jenkins said.

Getting the lead out

As conservationists, hunters play a pivotal role in the reintroduction and their response to helping the condor has been positive.

In a pilot program considered the first in the country, hunters on the Kaibab Plateau have been voluntarily using non-lead ammunition. As an incentive, each hunter who pulls a tag for this area receives two free boxes of copper bullets and is educated on the problems facing the condors.

The creative solution between area land managers, the Peregrine Fund and the hunting community began three years ago and is gaining acceptance, officials report, thereby reducing condor deaths from lead poisoning.

“In 2007 we had 83 percent voluntary compliance and no condor deaths from lead poisoning, so we are very proud of the hunting community — they have been very supportive,” reported Kathy Sullivan, condor-program director for the Arizona Department of Game and Fish.

In 2006, there was 60 percent compliance and four condor deaths from lead poisoning, Sullivan said.

In addition, hunters are advised that if they choose not to use non-lead ammunition, to bury the gut pile and unused carcass or bag it and bring it to a designated drop-off station at the Jacob Lake check station.

Those who do use the copper bullets provided, or some other non-lead bullets such as brass, should leave the gut pile and waste sections for the condors, Sullivan said. Copper and brass are not considered threats to the birds’ health.

Education and outreach is the key to raise awareness of lead’s impact on the condor, rather than a ban, Sullivan said. In addition to the free-ammo program, letters and fliers are sent to 300 regional hunter-licensing outlets each year explaining the issue. Fliers are posted as well to alert sportsmen engaging in year-round hunting activity, such as for varmints. Another hurdle is that non-lead bullets are not well known or readily available, although that is beginning to change.

“The biggest problem is availability of non-lead ammunition,” Sullivan said. “Hunters tell us they are as effective as lead-based bullets, plus they do not fragment as much in the shot animal.”

The bullet program costs $100,000 per year, she said, and funding comes from Arizona lottery revenues, the Wildlife Conservation Fund and Indian gaming, among other sources.

Similar programs are being considered in Utah and Wyoming, to which the birds occasionally fly, Sullivan said. She added that a lack of funding prevents the program from extending into the Grand Canyon.

“With the help of hunters this is definitely a manageable problem.”

A ban not considered

Officials opposed an outright ban on either lead bullets or hunting on the Kaibab. Another regulation does not sit well with the hunting community. Plus, the volunteer program has been reducing deaths, and condors rely on the carcasses hunting provides.

“In California, they banned leadbased bullets and hunters there now will never listen to why lead-based ammo affects the condor, so we cannot alienate the hunting community,” Parish said.

Some media reports and hunter organizations have questioned this attitude, but their fears are unfounded, he said. The research has not been antihunting, but a process that focused on lead poisoning in condors and then followed the thread of evidence. Lead bullets came up the culprit.

“In our studies, we shot deer and then X-rayed them whole, and even animals with a clear pass-through still contained scary amounts of lead fragments,” Parish said.

The amount of lead so alarmed scientists that more studies were done as a public health concern.

“So it seems pretty straightforward, as we get a better handle reducing the amount of lead being used in the deer hunt, we see improvement with the condor,” Parish continued. “We want to spread that knowledge to the hunting community where people realize that it is a simple scientific solution.”

He pointed out that treatment for lead poisoning dropped from 70 percent of the condor population in 2006 to 50 percent last year.

Sullivan agreed that a hunting ban is not necessary. “It would be extremely hard to enforce, and hunters would not support it. Education will solve the problem, not putting another law on the books.”

Ag assists as well

Ranching also plays a role in bringing back the California condor, biologists explained. Dairy farmers in Phoenix freeze dead cows and then ship them to the condor facility. The “bait” allows researchers to capture the birds for check-ups and treatment, and for attaching transmitters and, on some, Global Positioning Units.

Ranchers in southern Utah are regularly seeing the condor as they explore their boundaries in this relatively new territory. The introduction was a mixed bag at first.

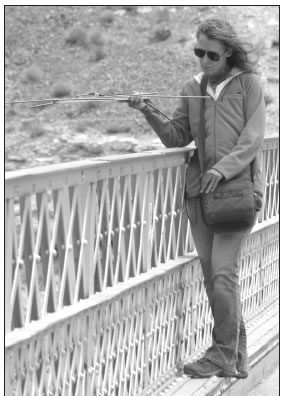

“They were wondering who the heck we were, wandering around with our [radio telemetry] antennas but now they greet us and help us locate them,” Jenkins said.

Condors apparently have a taste for lamb, but only post mortem. Ranchers follow them to keep track of dead livestock, plus they get a free clean-up.

Ranchers surrounding the condor habitat have voluntarily been using non-lead bullets, Jenkins said.

Wild return

Marti Jenkins, a biologist with the Peregrine Fund, tracks a radio-collared condor with a radio-receiver antenna at Navajo Bridge. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga.

Despite their success at the Vermilion Cliffs and Grand Canyon, California condors are still an endangered species. There are only 315 California condors today. Of those, 151 are living in the wild — 87 in southern California and Baja, and 64 in Arizona, according to the Peregrine Fund. The rest are in captivity, with 26 birds on schedule for a first-time release.

By 1987 only nine birds existed in the wild. In a desperate attempt to save the species, biologists captured them and successfully bred them in zoos.

When it was time to release them back into the wild in 1996, researchers realized that the birds hatched in captivity would not necessarily have the skills to survive on their own. The solution was to bring their biological cousins, the larger Andean condors, to act as mentors.

On May 10, during a keynote speech in Cortez for the Ute Mountain-Mesa Verde Birding Festival, Donald Bruning, a leading researcher and author on the condor, discussed the first release.

“When the California condors were released at Vermilion Cliffs, two Andean condors went with them so they would know what to do, where to find food, nesting sites and habitat,” Brunning said. “Then the Andean pair was captured and returned to South America.”

The birds have a slow reproductive rate, but finally in 2003 the much-celebrated first chick successfully hatched in the wild in the Grand Canyon. In the last five years, seven have been successfully born wild in Arizona. Human intervention and cooperation were key.

“Without captive breeding, we would not have California condors today,” said Bruning, who founded the California Condor Project.

“Success has been remarkable if not for the lead problem. So it is important to move towards bullets other than lead, because if it is a problem here then where else is lead poisoning a problem?”

Celebrity birds

Condors are the star of the show at the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. Maneuvering gracefully on updrafts created by the heating of the desert, the popular birds casually soar among sheer cliffs and spires, usually in groups.

As they hover over the circus of the South Rim, hundreds of tourists crane their necks in unison, cameras whirring away.

Ranger talks are given daily at an observatory. As if on cue, an adult condor approaches close, rising from below the cliff edge, casting a shadow. The excitement of kids and adults staring skyward says it all.

“My theory is that they are attracted to crowds, just like in the wild when they look for food,” the ranger says.

Despite their love of rotting meat, condors do not have a good sense of smell to find it, she says. Instead they use excellent eyesight to detect a gathering of other scavengers at a food source.

Condors follow turkey vultures, ravens, eagles and coyotes to carrion. Upon arrival, their enormous size and propensity to dine in large groups means they are first in line for the best parts.

Using a 9-year-old girl as a prop, the ranger illustrates how, at over 4 feet tall, an adult condor is an impressive species. Wingspan tops out at 9 1/2 feet, and adults can weigh between 25 and 30 pounds. By comparison, a bald eagle weighs up to 13 pounds and tops out at a 7 1/2-foot wingspan.

“I’ve seen a condor jump on an eagle’s back at a feeding site,” Jenkins recalled. “The eagle was flat on the ground screeching.”

While not seen definitively in the last 100 years in Arizona, fossil evidence shows the condor did fly here 1,000 years ago. They thrived during the Middle Pleistocene Age 100,000 years ago dining on mammoths, mastodons and saber-tooth tigers.

Their normal range is 50 to 70 miles from the Vermilion Cliffs release site. But younger birds will explore further, as if becoming reacquainted with a pre-historic range.

Twice in recent years the birds were tracked to Mesa Verde National Park, biologists report. Also they have visited Zion National Park and Escalante National Monument in southern Utah and around Sedona, Ariz.

The furthest voyage so far was Flaming Gorge reservoir, over 300 miles away in Wyoming. On these jaunts, the birds can soar at a dizzying height of 15,000 feet.

“Individual birds every once in a while take these oddball trips into new areas,” Parish said. “It is a mechanism of dispersal where these young, subadult birds are trying to get the lay of the land. After the journey, they usually return directly to their home range.”

If can they avoid death by lead or electrocution on power lines, the California condor has an impressive lifespan of 50 to 60 years. Breeding continues up to 40 years of age.

The condor is as comfortable on land as it is in the air. Huge feet offer stability on carrion, and allow the bird to walk around exploring, sometimes running at full speed away from researchers.

“They’re really fast; I’ve run flat out for a quarter-mile trying to capture one,” Jenkins said, adding that the birds are curious creatures with a knack for destruction.

Campers need to be especially aware of the condor presence because “they will rip a camp to shreds looking for food,” she said. “Keep food tightly stored, the same behavior you would use in bear country.” If you’re fortunate enough to see a condor on land, stop and enjoy the wildlife encounter, but if they approach a campsite or person, condors should be chased off, she said. “We don’t want them to associate food with people so they stay wild.”

Other antics witnessed by biologists include condors playing with sticks, sneaking up on ravens to scare them and quarrelling with golden eagles.

Other than the South Rim and Vermilion Cliffs, additional places to spot condors are at Navajo Bridge and Marble Canyon. For a good laugh, use binoculars to view the birds taking turns “showering” at a permanent leak on the Springs pipeline visible from the South Rim.

Ideally researchers hope to establish three flocks of condors at 150 birds per flock. With continued funding and intense management, along with 100 percent compliance under the nonlead program, the condor should survive, managers predict.

“In 20 years we went from nine condors to more than 300,” Bruning said. “I would love to see condors nesting at Mesa Verde and other places.”