New rules proposed by the Bush administration would change how air quality is assessed in the nation’s most pristine areas, making it easier to build power plants near sites such as Mesa Verde National Park.

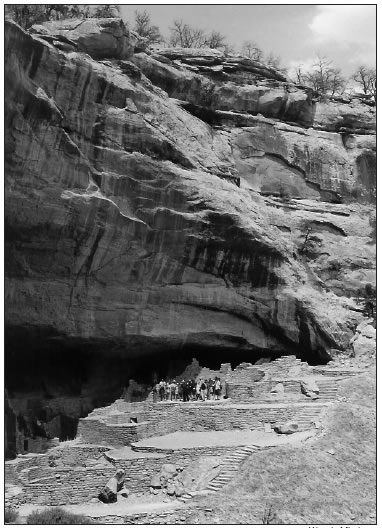

Cultural resources such as the Wetherill Ruin at Mesa Verde National can be damaged by some forms of air pollution. Proposed rule changes at the Environmental Protection Agency could worsen pollution in national parks, critics say. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga.

Although the new Environmental Protection Agency regulations have been widely criticized, they are likely to be implemented this summer. They could have the effect of allowing more pollution in national parks and wilderness areas at a time when concerns about air quality in some such areas is already growing.

“What we’re concerned about is that the changes would enable areas directly around national parks to be considered more favorably for coal-fired power plants,” said Mike Eisenfeld, a New Mexico-based organizer for the nonprofit San Juan Citizens Alliance.

“With our [air-quality] situation being pretty precarious, the last thing we need is to be adding additional plants.”

The new regulations would change the way pollution is measured at areas designated as “Class 1” under the Clean Air Act. Class 1 areas include primarily national parks and monuments and wilderness areas.

There are 156 Class 1 areas across the United States, including many but not all national parks. In the Four Corners region, Class 1 areas include Mesa Verde, Canyonlands, the Weminuche Wilderness Area, and the Grand Canyon. Chaco Culture National Historical Park, on the other hand, is considered Class 2.

Class 1 airsheds are given the highest protection, explained Karen Hevel- Mingo, senior program coordinator for the Southwest Regional Office of the nonprofit National Parks Conservation Association.

“It [the designation] doesn’t preclude building a power plant nearby,” she said, “but they have to be much more diligent in making sure they have the best available technology and they are controlling emissions as much as possible.

“This will have the effect of making it much easier to site coal-fired power plants near national parks.”

In a letter to EPA Administrator Stephen Johnson dated June 23, eight senators including Colorado’s Ken Salazar expressed opposition to the proposed rule changes.

Taking an average

The rule changes would alter the way the impact of a new, nearby pollution source on a Class 1 area is assessed.

For decades, pollution levels near Class 1 areas have been measured over short times, such as three-hour and 24- hour periods, depending on the pollutants, to capture peaks in emissions. Under the new rules, those peaks would not be used to assess pollution. Instead, an annual average would be substituted — making it more likely that new power plants such as the proposed 1,500-megawatt Desert Rock in northern New Mexico could be constructed without having to implement strict air-quality mitigation measures.

Eisenfeld said that would be a mistake, given local concerns about air quality.

The Four Corners Power Plant near Fruitland, N.M., is the No. 1 emitter of nitrogen oxides in the nation, he noted. The San Juan Generating Station just a few miles away was 21st among all the nation’s power plants in its emission of nitrogen oxides in 2004.

Ozone levels in San Juan County, N.M., probably will exceed federal safety standards this summer, “and no one’s thinking about the economic implications.”

“One of the most fascinating things we have in the Four Corners is our natural areas,” he said. “But when people come to Farmington or Cortez or Durango they’re going, ‘Hey, what’s with the air quality?’ It’s not a pretty thing.

“My opinion is we should be doing everything we can to protect our national parks and wilderness areas, which clearly rely on their air quality as part of their appeal,” Eisenfeld said.

Power plants are a huge contributor to regional pollution, he said. “We just don’t have that many vehicles. All indications are that it’s the power plants.

“The power plants are saying, ‘It’s coming from Asia.’ I get tired of them saying they’re not contributing to much of anything. My sense is they’re a pretty significant source of pollution.

“It’s absurd we would even be considering another power plant here.”

Eisenfeld said the rules change could have a long-term impact even if the Desert Rock plant is not built.

“Even if Desert Rock meets an untimely death, there might be other projects,” he said. “The Ute Mountain Utes may want to build a power plant with water from A-LP [the Animas-La Plata water project]. We keep hearing that.”

Hazy vistas

Air pollution in national parks is of concern for two main reasons. It can damage health, and it impairs visibility.

Haze is something that visitors notice immediately. The main cause is fine particulates, though nitrogen-oxide compounds and nitrate particles contribute to the problem.

At Mesa Verde, visibility on the worst days is declining significantly, according to a recently issued report by the NPCA called “Dark Horizons” that labeled Mesa Verde one of the nation’s 10 national parks most threatened by new power plants. Capitol Reef and Zion in Utah were also on the list.

George San Miguel, natural-resource manager at Mesa Verde, agreed that visibility is worsening in the park.

“We’re seeing more dirty days. Overall the trend is downward,” he said. “And views are one of the factors that make Mesa Verde a special place. The ability to see what the ancient Native Americans saw — the mountains in the distance, the night skies, the forest in front of them — all these things are important so visitors can immerse themselves in the past.

“When there’s air pollution, it reduces the visitors’ ability to immerse themselves, because the industrial world is following them into the park.”

Particulates also have adverse health effects.

Another major concern is ozone.

Formed when nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds interact in the presence of sunlight, ozone can damage lung tissue and is a particular concern for people with diseases such as asthma.

Ozone has no effect on visibility, but it poses a special problem for parks and wilderness areas because it harms animals and plants as well as people.

“It is a highly reactive molecule that when inhaled by a plant leaf or a lung is very damaging to the tissue,” said San Miguel.

Ozone reduces crop yields and slows the growth of trees, he said. Aspen and yellow pine species such as ponderosa are especially sensitive to ozone. It can also harm wildlife.

Mesa Verde’s ozone levels have been slowly approaching the federal safety limit. Peak levels have been rising over the years, San Miguel said, and the overall amount of ozone is also going up at the park, “which means even the better days are getting worse.”

According to a National Park Service report, ozone is a growing concern across the West. Although ozone levels are holding stable or declining in the East, probably because of improved pollution controls, nine national parks in the West showed worsening levels, including Mesa Verde, Canyonlands, Death Valley, Glacier, Petroglyph and Rocky Mountain.

Plethora of pollutants

At the Grand Canyon, particulates and ozone are special concerns.

“”Particulates are an issue chronically because of the visibility problems they cause, especially in summer, when we’re downwind of the big sources to the south and west of us [Phoenix, Los Angeles and Las Vegas],” said Carl Bowman, air-quality specialist for the national park.

“We pretty much all the time have some regional haze, and sometimes it gets kind of thick.”

However, the park has only exceeded the EPA’s particulate standard on a couple of instances.

In the winter, air flows more from the northwest, through central Nevada, bringing less pollution, he said.

And precipitation tends to wash pollution out, so in the winter, after a big storm, “we have brief periods where the air is as clean as it can be.”

Discerning long-term trends can be difficult, he noted. “Unfortunately, I haven’t been here long enough and neither have the instruments, to predate the power plants and other major developments, so we don’t have any of that nice pristine baseline to judge by,” he said, adding with a laugh, “It’s a shame the Anasazi didn’t have particulate monitors.”

However, it does appear that at the Grand Canyon, the cleanest days are getting cleaner, while the dirty days are not. “For a while they were getting cleaner, but in the last few years that has leveled off,” he said.

As at Mesa Verde, ozone levels have been creeping upward at the Grand Canyon, Bowman said, “ever since we started monitoring for it back in 1989.”

The levels have not yet violated the EPA’s new, tougher ozone standard, adopted in March, but they’re getting very close.

Bowman thinks ozone will continue to be a major concern at the Grand Canyon. “With the ongoing drought there’s more sunlight to make that conversion [to ozone], and depending what happens with climate change, the higher temperatures and reduced cloud cover might serve to increase that reaction rate.

“It’s kind of a troubling prospect that ozone might continue rising despite our efforts to reduce it.”

Other pollutants are of concern as well. Sulfur dioxides and nitrogen oxides both can cause acid rain or snow, or acidic particles. Both Mesa Verde and Grand Canyon monitor for acid deposition, both wet and dry. However, acidity tends not to be a problem in either place because the soils and rocks contain much sedimentary and carbonate material, which neutralizes the acid.

Nitrogen deposition is still a problem, however, because it acts as a fertilizer, encouraging the growth of exotic species but not helping native desert plants, Bowman said.

And Hevel-Mingo said sulfur dioxide is a concern in another way.

“There’s data coming in from different studies that show it can have an impact on cultural resources,” she said. “It can weaken the layer that bonds the stones in archaeological sites.”

Seeking offsets

Bowman said the proposed rules change would not alter monitoring at the Grand Canyon, but rather the way the data is used.

“Any time you look at an average, you’re looking at a tradeoff,” he said, noting that people’s visual experiences do not occur in “averages.”

“If someone walks up to the edge of the Grand Canyon, their eyes register the view in a tenth of a second. It’s an instantaneous experience, not an average.

“If there is just one yearly average things are a lot easier, but what are we losing in terms of refinement?” Individual parks don’t make statements for or against proposals such as the rules change, San Miguel noted, nor do they come out with positions on projects such as Desert Rock.

“When there’s a proposal such as Desert Rock, or adding thousands of gas wells outside Farmington or east of Durango, we let them know we’re not happy with the air getting dirtier. We don’t point our finger at one industry or state or tribe. We just say the air quality is deteriorating and the mission of the park is at stake.”

Monitoring data is used in computer models that predict what the impact of something such as Desert Rock will be. “Our models have indicated there would be a negative impact from adding another regional sources,” San Miguel said, “so the National Park Service as an agency told the EPA that in order for Mesa Verde’s air quality to not be impaired, these kinds of offsets would be necessary.”

Changing the way air quality is measured would mean those offsets would probably be less significant, according to the NPCA’s Hevel-Mingo.

“You may have days where the pollution is God-awful in the parks, but if they’re not taking that into account, if they’re just producing an average, it’s going to make a big difference.”

Looking for solutions

NPCA’s “Dark Horizons” report recommends keeping the current clean-air laws for Class 1 areas rather than weakening them; forcing older coalfired power plants to reduce emissions; passing federal legislation to cut emissions of greenhouse gases; and looking to alternative energy rather than coalbased power.

Hevel-Mingo added that more monitors would be helpful. “There’s an ozone monitor in Zion and some in the Arches/Canyonlands area, but there’s a lot of territory between those monitors,” she said.

Eisenfeld supports those recommendations and wants to push for renewable energy. Opponents of Desert Rock are looking into the feasibility of building a concentrated-solar-power facility on 11 square miles on the Navajo Nation.

“We’re getting past the days of cheap energy,” Eisenfeld said. “Coal-fired power plants are a fairly expensive way to produce energy. Until we get a grip on this and figure out ways to subsidize the right things, we’re going to be in some significant quagmires.”

San Miguel noted that many sources contribute to pollution. Volatile organic compounds, those contributors to ozone, are produced by everything from vegetation to oil fields.

“Volatile organic compounds are both natural and artificial,” San Miguel said. “Native vegetation produces a lot. So do all these gas fields and oil fields. When you pump gas into your car and see those vapors, that’s VOCs.”

Wildfires, fossil-fuel combustion, even the burning of trash all give off nitrogen oxides that “contribute to the ozone production factory,” he said.

“We’re all part of the problem,” San Miguel said. “I drive to work. We’re all contributing.”

Grand Canyon makes extensive use of natural-gas-powered shuttle buses that carry visitors from site to site. Although they were adopted primarily to reduce traffic, they have undoubtedly helped cut pollution, Bowman said — not only tailpipe emissions, but dust raised by tires.

But to put it in proportion, a study estimated that the total vehicle miles traveled in the park by visitors, concessionaries, and staff was 44 million per year. In Maricopa County, Ariz., about that many vehicles miles are driven every day — before lunchtime.

On the bright side, Bowman said, considering how fast the Southwest is growing, “the fact that ozone isn’t rising any faster is cause for hope.”

Still, air pollution is an issue that “we just have to keep working on.”

“People sometimes think, ‘We’ve done this, we’ve solved it. We’ve gone to low-sulfur diesel, or catalytic converters, so the problem is fixed.’ But the number of sources keeps going up, so we have to keep looking for ways to improve.”