I was busily weeding in my back yard one August day when I sat on a lawn chair for a short break. A sharp pain in my arm made me wonder if I’d cut myself.

Then I realized that, no, I’d been stung, apparently by a wasp. Though I hadn’t noticed them till now, there were plenty of them buzzing around, easily identifiable by their pinched-in “wasp” waists and their long back legs dangling.

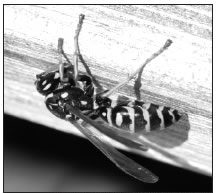

The European paper wasp has invaded the United States. Its habit of building many nests all over a back yard mean it can cause problems for homeowners. Photo by Whitney Cranshaw/CSU/Bugwood.org

My tender forearm swelled to about the size of a Nerf football. For a week, the skin around the sting was as sore as if it had been burned. Then followed another week of fierce itching.

I was innocently taking out the trash soon after when yow! again with the gom jabbar, the poison dart. I’d been stung once more, an inch from the original site. Again I had to endure the swelling, the burning, the horrible itch.

After 16 years of co-existing peacefully with my backyard bees and yellow jackets, never once being jabbed with their hostile needles, I’d been stung twice in one month. I was afraid to do yard chores without donning a long-sleeved coat, hood, and gloves. What was going on?

I picked up an information sheet at the Colorado State University Cooperative Extension Office in the county courthouse and learned that a new species, a foreign invader called the European paper wasp (P. dominula), has moved into Colorado. Its habit of building nests in many different locations around a yard “has greatly increased the incidence of stings,” the fact sheet said.

Spreading rapidly

According to the web site www.livingwithbugs. com, European paper wasps arrived in North America some time prior to 1981 and have spread rapidly in recent years, lacking their natural parasites and predators. In addition, according to Penn State’s entomological web site, www.ento.psu.edu/extension, they establish colonies earlier than native wasps and are outcompeting them.

The replacement of native paper wasps by European ones would not matter much to the ordinary person except for one thing: Whereas native paper wasps tend to make nests in high, inaccessible places such as under roof eaves, the European wasps build in all sorts of places where people might encounter them.

“They like enclosed little cavities like the end of a small pipe, maybe the T pipes for clothes lines,” said Tom Hooten, CSU Extension agent for Montezuma County. “They don’t build their nests in the open like most paper wasps.”

In addition, they are “very attentive to potential threats to their nests,” according to the Penn State web site, meaning they are likely to sting unsuspecting folks.

Some experts believe the European invaders are rather bad-tempered. “The European. . . attacks people with much less provocation than the native paperwasp,” says another web site, http://bluebird.htmlplanet.com, which calls the species a major threat to cavity- nesting birds because of its proclivity to build nests in bird boxes.

However, entomologist Whitney Cranshaw, a professor at CSU in Fort Collins, Colo., doesn’t believe the insects are all that bad.

“I don’t think they’re that aggressive,” he said by phone. “I have yet to be stung by one, and I get right in their face when I take pictures of their nests.”

It’s difficult to tell the invaders from the native wasps, he said, as both have yellow and black stripes. However, the Europeans are present in Colorado, including the Four Corners area.

“You’ve probably had them at least a decade,” Cranshaw said.

Cranky SOBs

In addition to wasps, stinging insects in the area include yellow jackets, which are a bright yellow and black (brighter than honeybees) and lack the pinched wasp waist; hornets (stout-bodied and darkish), honeybees, and bumblebees (native bees, with a red stripe in addition to the yellow and black). All live in colonies and build nests.

The western yellow jacket is a real nuisance, according to Cranshaw, and is believed to cause at least 90 percent of the painful “bee stings” in Colorado.

“I don’t get near their nests,” he said. “They’re really cranky SOBs and inclined to sting.”

Because they will scavenge garbage, food and dead insects, they hover around picnic areas, trash cans and even the grills of cars. “They will come and sit on your plate,” Cranshaw said.

Stings are merely painful to most people, but about 1 percent of the population is allergic to stings by bees, wasps, hornets, or yellow jackets. Anyone who is stung multiple times at once, who is stung in the eye, or who experiences difficulty breathing, dizziness, nausea, or hives following a sting, should seek medical treatment. It is possible to become allergic even if you’ve been stung before.

Yellow jackets nest underground or in dark, enclosed areas of buildings. Hornets build big, football-sized, gray nests that are covered on the outside.

Wasps, in contrast, make fist-sized, papery nests with open cells.

Yellow jackets can be killed by commercially sold “traps” that contain a poisoned bait. Unfortunately, they don’t work on paper wasps.

“At least in eastern Colorado, people have been seeing more [wasp] nests in recent years and buying more traps but they don’t catch the European paper wasps,” Cranshaw said. “I tested them all last year and only yellow jackets go in those traps.”

Hungry predators

Paper wasps, unlike bees, don’t pollinate fruit or flowers. They eat live insects, mainly caterpillars, which means they can be very useful at controlling garden pests.

On the other hand, they can decimate butterfly populations as well.

“They have had a tremendous effect on backyard insect life,” Cranshaw said. “I totally changed my garden talks for the Master Gardener series because some of the things I used to talk about, like hornworms and cabbage worms — they’re gone in most backyards. The wasps are eating them.

“I don’t talk about butterfly gardens any more, at least in eastern Colorado, because they involve planting plants that caterpillars would develop on, and again, the paper wasps are eating them.”

The wasps pose another problem. Although their larvae subsist on live insects, they apparently have developed a taste for ripe fruit. “They can do a lot of damage to grapes,” Hooten said.

In the Tri River area of Colorado, (Delta, Mesa, Montrose, and Ouray counties), paper wasps have damaged sweet cherries and peaches, according to Cranshaw. “That’s not supposed to happen.”

If you like the idea of a natural predator controlling the larvae that eat your broccoli or tomatoes, you may want to leave the paper wasps alone. Just remember that their nests might be anywhere — use caution if you approach any cavity in a pole, tree, or roof eave. I eventually found a wasp nest on my back fence, near the garbage can.

But if you want butterflies or are fearful of being stung, you may want to keep the wasps down. The best way, according to the experts, is to spray the nests with a commercial wasp/hornet pesticide, the type that sprays at least 20 feet. Do it in the early morning or evening, when the insects are most likely to be at home.

Most of the stinging pests will disappear with cold weather; only fertilized queens survive the winter. The best time to get a jump on them is in early spring, when the wasps are just starting to build new nests.