“There continues to be this fallacy that natural gas is clean. But for affected communities there are a lot of impacts, of which methane is one.” — Mike Eisenfeld, energy and climate program manager, San Juan Citizens Alliance

A furious fight is raging over the greenhouse gas methane — a fight that has particular relevance for the Four Corners.

In October 2014, NASA released a report about a study demonstrating that there was an atmospheric concentration of methane over the region.

The research, published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, measured greenhouse gases from 2002 to 2012 using observations made by a European Space Agency spectrometer. The methane “hot spot,” as it has come to be called, persisted in the atmosphere throughout the study period, and was independently verified by a ground station at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico.

The enlarged image shows more exactly where the “hot spot” is located. The red shows the concentration of methane emissions; darker red means higher emissions. Courtesy of San Juan Citizens Alliance.

Seeking the source

The authors concluded it was energy development. They wrote that “long-established fossil fuel extraction, at least in the Four Corners region, likely has larger [methane] emissions, and subsequent greenhouse gas footprint, than accounted for in current inventories.”

Natural gas is 95-98 percent methane, and the hot spot sits primarily over the San Juan Basin, where there has been substantial oil and gas activity ever since the 1920s. The hot spot is approximately 2,500 square miles –the size of Delaware – largely in Colorado and New Mexico but also encompassing parts of northeastern Arizona and southeastern Utah.

But factors other than natural-gas production can result in atmospheric methane. The gas is released into the atmosphere from the ocean, agricultural operations such as feedlots, landfills and waste processing, and naturally occurring geologic seeps. Methane is colorless and odorless, and difficult to measure, which is why the NASA space-based observation was notable.

Because of the difficulty of specifying the sources of the hot spot, researchers used other methods to determine more precisely where the methane is coming from. In April 2015, a year after the NASA photo was published, a team of researchers conducted an “airborne campaign” in the Four Corners region. They measured methane plumes, using next-generation spectrometers. They detected over 250 methane plumes coming from infrastructure associated with natural-gas harvesting, processing and distribution, including processing facilities, leaky pipelines, storage tanks, well pads and a coal-mine venting shaft.

Ground teams visited the sites to document the leaks. As a result, some wells, tanks and pipelines have been shut down.

These studies seem to demonstrate that the natural-gas industry is primarily responsible for the elevated levels of methane. The San Juan Basin is home to 26,000 active oil and gas wells, and over 11,200 abandoned ones, many of which are leaking methane.

“When you live in a place like Farmington, you’re in close proximity to hundreds of natural-gas facilities that run all the way from the wells to the pipelines to the processing facilities,” noted Eisenfeld. He’s been in the area for over 20 years, working with San Juan Citizens Alliance for the past 11. “It’s really important for people to understand we have extensive natural-gas development already and that it’s inherently tied to the methane problem, there’s no doubt about it.”

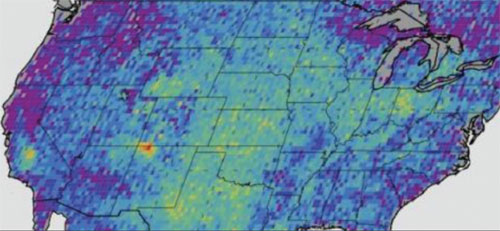

The Four Corners area, showing red in this image released by NASA in 2014, is the major hot spot for methane emissions. The map shows how much emissions varied from average background concentrations from 2003-2009 (dark colors are less than average and lighter colors higher). (This is the original image, and to date the only one released by NASA.) NASA/JPL-Cal Tech Univeresitiy/Univ. of Michigan

Ticking clock

“Obviously, methane is a very powerful greenhouse gas. It contributes to ozone formation, which has pretty serious public health impacts in many places.” – Michael Saul, senior attorney, Public Lands Program, Center for Biological Diversity

Saul, an attorney involved in litigating environmental issues on public lands, knows ozone formation to be one deleterious effect of methane. But not many people know about methane’s role as a greenhouse gas, or why ozone formation is problematic. While the link between climate change, rising carbon levels, and human activities is still hotly debated in some circles, scientific measurements are clear.

The level of atmospheric CO2 is rising quickly. Click on Bloomberg’s “carbon clock” (a real-time estimate of global monthly atmospheric CO2) at https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/ carbon-clock/ to see how fast this is happening.

When the first measurements of CO2 took place in 1958, carbon was present at 316 parts per million. It is now, in January 2018, at 406 ppm. According to the Bloomberg clock website, for 800,000 years before industrialization the levels were around 280 ppm, and the rapid rise in the past 50 years is believed responsible for many of the changes in weather patterns worldwide.

Carbon dioxide is just one of several greenhouse gases, and each one has the potential to impact the world’s atmosphere, weather and human health. Besides methane (CH4), other greenhouse gases are nitrous oxide (N2O), water vapor, ozone, and industrial gases including hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3). All of these except water vapor and ozone are included in international and national atmospheric estimates.

Together these gases create the “greenhouse effect,” meaning they trap heat in the atmosphere and lead to warming, similar to what happens when sunlight shines on your closed car windows. Without this greenhouse-gas action, earth’s temperature would be too low to support life as we know it. But too-hot atmospheric temperatures are also a threat to life as we know it. Climate change as a result of increasing temperatures worldwide can be seen in changes in storm patterns, including extreme, erratic and unusual weather such as this winter’s snow in the southern U.S. and lack of it in the San Juan Mountains.

Rising levels of methane are particularly worrisome because it is a more powerful greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. According to the San Juan Citizens Alliance website, methane is far worse for the climate than carbon dioxide – 86 times more potent. This means that increased levels of atmospheric methane could contribute more to climate change than carbon dioxide.

Until the recent project measuring methane from space, there was no baseline from which to document changes in atmospheric methane, and to date, methane is mostly left out of the climate- change conversation.

Saul and Eisenfeld both belong to organizations that are fighting to ensure that methane does not continue to be released into the atmosphere.

But the energy industry and the Trump administration have other ideas.

Over the past year there has been a back-and-forth between the administration and environmental groups over an Obama-era rule to regulate methane emissions. The actions include executive orders, lawsuits, a Senate vote, and most recently, a lawsuit filed on Dec. 19 against the BLM, the Interior Department and Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke by a coalition of 17 environmental groups.

A strategy to cut methane emissions was a part of the Climate Action Plan of 2014. This plan addressed the four main sources of methane: landfills, coal mining, agriculture, and oil and gas production. The plan called for updating standards, with public input, to reduce emissions from landfills and outlined voluntary strategies to cut emissions in the dairy industry by 25 percent by 2020 through the use of methane digesters.

It called upon the BLM to gather public input on programs for the capture, sale and disposal of waste methane associated with coal mining on public lands.

It also took “new actions to encourage additional cost-effective reductions” in the oil and gas industry, including voluntary programs and regulations. A key element was updating standards to reduce flaring and venting on public lands.

This plan resulted in two “rules” to limit methane emissions – the EPA’s and the BLM’s. The EPA rule was adopted in 2016 and applies to new and modified oil and gas facilities. It requires oil and gas companies to stop leaks of methane and volatile organic compounds, and requires the gas lost in production, processing, transmission, and storage to be captured, including not only natural-gas wells but oil wells.

The BLM rule similarly requires oil and gas producers to dramatically reduce methane waste on federal public lands.

Reducing waste

“The rule that came out, from our perspective, is a pretty modest one – it doesn’t ban all venting and flaring – rather, it requires operators to take some reasonable measures – in most cases measures that pay for themselves.” — Michael Saul

Saul told the Free Press that the rule has been in effect for some time already but had phased-in compliance dates for industry for most of the things operators were required to do. The requirements for leak detection and control don’t take effect until January 2018, he said.

The rules require oil and gas operators to capture and sell the gas currently being released into the atmosphere, better maintenance to prevent leakage in pipes and wells, and minimizing of venting and flaring.

Flaring is done when a well is designed to produce oil, but methane is present as a byproduct. The producers burn or “flare” any natural gas deemed uneconomical to collect and sell. Gas mixed with toxic hydrogen sulfide is also often flared due to safety issues, since flaring converts the gas into a less-toxic substance.

However, the process of flaring not only burns gas that could be utilized, but produces toxins and VOCs including benzene, formaldehyde, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs, including naphthalene), acetaldehyde, acrolein, propylene, toluene, xylenes, ethyl benzene and hexane. Over 60 different air pollutants have been measured downwind of natural-gas flares in Canada. Venting is the direct release of gas into the atmosphere, without burning.

Venting happens during maintenance (of wells, tanks, pipelines) and also during the development and completion of wells. Abandoned wells and storage tanks have the potential to vent also.

A 2010 U.S. General Accounting Office report states that “around 40 percent of natural gas estimated to be vented and flared on onshore federal leases could be economically captured with currently available control technologies. According to GAO analysis, such reductions could increase federal royalty payments by about $23 million annually and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an amount equivalent to about 16.5 million metric tons of CO2—the annual emissions equivalent of 3.1 million cars.”

Saul told the Free Press that the evidence was “pretty overwhelming that the cost of complying with these rules would be something like under 1 percent of their profit, even for the small companies.”

He added, “This gas is a valuable commodity – if they capture it instead of let it leak, they can sell it and make a profit. Just two months ago, there was a study that found that the wasted methane from leaking, venting and flaring in New Mexico alone is somewhere between $182 million and $244 million worth of gas each year – that is about $27 million in lost tax revenues.”

Laura King, attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center, commented, “This rule had overwhelming public support and it is in the public interest and in the interest of the environment. This is a rule that saves money and is good for industry – it saves them money.”

Money and politics

“If you’re allowing methane to be emitted into the atmosphere then you’re missing out on the royalties, which is dumb.” — Mike Eisenfeld

“There is no reason those regulations should not be put in place, for our environment, for people’s health; and for the industry itself, to save them money.” — Carrie King, associate director, Great Old Broads for Wilderness

However, despite a long public review process, and despite the potential for increased revenues, the Trump administration has fought hard to delay

the implementation of the methane rule. The BLM tried two times to delay the compliance deadlines. In June 2017 the agency announced an indefinite “stay” of all provisions of the rule. The Conservation and Tribal Citizen Groups and the states of California and New Mexico responded by filing a lawsuit in U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. On Oct. 4 the BLM was ordered to vacate the stay and reinstate the rule.

The next day, the BLM submitted a different proposal to delay compliance with that court order (which included a 30-day public-comment period to comply with existing law), and on Dec. 8 revised that proposal to request a delay for a year, until Jan. 17, 2019.

In response, a coalition of 17 environmental groups, including national groups as well as the local San Juan Citizens Alliance and Diné Citizens Against Ruining the Environment, filed a suit challenging the BLM’s amendment of the compliance deadlines.

“Our concerns have been ignored and communities like ours are only looked at for exported revenues and royalties,” said Eisenfeld.

Saul added, “The important thing to remember is that this is public oil and gas –under the Mineral Leasing Act, the federal government leases the public’s resources to private companies to extract.

“But the bounds of that statutory arrangement stipulate that those companies aren’t entitled to waste that gas. The BLM has not just an authority but a legal obligation of not simply maximizing income on private property but to ensure that the public, including the states who get about half of that royalty, are getting a fair return on the resources.”

Eisenfeld ticked off six reasons why it is important to keep the methane rule in place: “Number 1, the sheer waste; 2, the public health implications; 3, climate change implications; 4, the methane cost, meaning the cumulative public health problems associated with those emissions; 5, royalties and revenue issues – these emissions are on federal lands, and as a part of the leases that these companies hold the states are due their royalties; and 6, this rule went through a robust public involvement process, which was absolutely shoved aside.” Laura King of the Western Environmental Law Center said her organization filed a Freedom of Information Act request to find out why the BLM was trying to delay the rule in spite of widespread public support and in the face of evidence demonstrating that the rule would minimize emissions, improve public health, and increase income for both the companies and the states through the capture of gas now being wasted.

She said that basically, the administration “is buying themselves time to do a larger rulemaking process to replace the current rule.”

Saul agreed. “The administration’s priorities are clear – they want to promote oil and gas drilling at all costs and our position is that in doing so they are ignoring the public financial hit, ignoring public health, ignoring the climate burden of this activity and ignoring the law.”

The 17 organizations have been working together on this issue for several years, along with the Western Environmental Law Center and a couple other legal firms. Saul seems hopeful as to the outcome of the latest lawsuit: “This is a pretty modest rule, and Colorado has already at the state level put forth regulations to require similar leak detection and methane waste minimization.

“In New Mexico, the attorney general and the delegation have strongly supported this rule, both for the health benefits and the financial impact to New Mexico.”

King said a motion has been filed seeking a preliminary injunction to stop the delay, “so we’re trying to move this along as quickly as possible, hoping that the methane rule will continue in effect as scheduled in January 2018.”

The delay actually causes uncertainty for oil and gas operators, since they do not know whether they will have to begin capturing the wasted gas this month or if they will have another year to see what happens.

Currently the rule remains in effect, pending a ruling about the injunction.

So 2018 may see a reduction in methane waste in the San Juan Basin. Or, come mid-January, the rule could be delayed a year, as the Trump administration wants, and ultimately be reversed.

“It’s a very modest and cost-effective step and the Trump administration’s repeated attempts to undo it are truly radical,” Saul said, “and they don’t reflect the interests of the people of Southwest Colorado and northwestern New Mexico who bear the brunt of air pollution and lost revenue.”

Eisenfeld concurred. “You have federal agencies like the BLM basically being directed to ignore rules by their parent agency, the Department of the Interior, and the current presidential administration. They’re doing everything they can to avoid their responsibilities. It’s very poor stewardship of our public lands, our public health and our civil rights.”