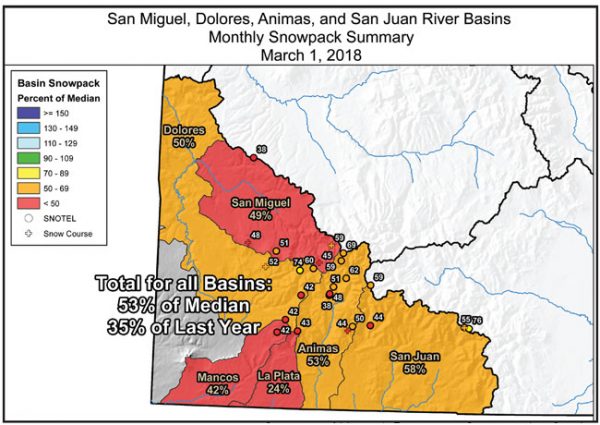

The San Miguel, Dolores, Animas and San Juan River Basins had just 53 percent of median snowpack as of March 1. Courtesy of Natural Resources Conservation Service.

As we face yet another year with low snowpack and uncertain flows in the Dolores River, the word “drought” has beenis being heard on the lips of many newscasters and water planners. Whether pronounced “drouth” or “dr-out”, the definition of drought and its potential impacts on water users vary as much as its pronunciation.

Until the St. Patrick’s Day storm, winter 2018 was looking an awful lot like 2002, a year with barely any measurable precipitation in the Four Corners. The low snowpack that year resulted in most irrigation users in Montezuma and Dolores counties getting only one-third of their allocation, even though the parched land could have soaked up much more.

A map developed by the National Integrated Drought Information System reporting drought status in Colorado as of March 20 of this year showed the southwest corner of the state in bright red, indicating extreme drought.

The definition of drought included in the recently completed Dolores Project Drought Contingency Plan is, “A period of insufficient snowpack and reservoir storage to provide adequate water to urban and rural areas.” (According to this definition, a drought is determined by snowpack levels, reservoir storage, and water demand.)

Snowpack is measured in terms of “snow-water equivalent” at SNOTEL sites in the watershed. The levels are compared to long-term data. As of March 1, the San Miguel, Dolores, and San Juan river basins had 53 percent or less of long-term water-equivalent at their SNOTEL sites as reported by the Natural Resources Conservation Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. (Shown at right.)

The SNOTEL data is combined with long-term weather forecasts to predict flows in major rivers. The Colorado Basin River Forecast Center, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, prepares the forecasts for the Dolores River. These forecasts are used by the Dolores Water Conservancy District and others to predict water allocations. The mid-March forecast as reported on the DWCD website read as follows:

“The runoff forecast has dropped since January: as of March 1st, the CBRFC 50% exceedance forecast for McPhee April through July inflows was only 113,000 AF. The SNOTEL sites are averaging only 46% of the median snow pack as of today, March 15th — down from the beginning of the month.”

Here’s a translation: The predicted Dolores River runoff, or inflow volume, to McPhee Reservoir has dropped since the beginning of the year. The median water-equivalent snowpack as measured at SNOTEL sites in the Dolores River basin dropped from 53 percent on March 1 to 46 percent on March 15. The “CBRFC 50% exceedance forecast” refers to the probability that the inflow to McPhee Reservoir will exceed the predicted inflow level in acre-feet (an acrefoot amounts to 325,851 gallons of water). Therefore, CBRFC’s prediction is that there is a 50-50 chance that inflow to McPhee Reservoir between April and July will exceed 113,000 acre-feet.

Timing is everything

The other factors that determine a drought (reservoir storage and water demand) are a function of timing. Water storage is dependent on capacity and carry-over. Capacity is the amount of water that the reservoir can hold. Ask any Dolores River whitewater boater when McPhee is “full,” and they will likely answer “6924.” But asking how much water that is will probably elicit a shrug.

The number “6924” refers to the lake’s elevation, or 6924 feet above sea level. According to DWCD, when the reservoir reaches this elevation, it is full, and has about 229,000 acre-feet of water available for irrigation and other uses of the Dolores Project. Since every drop of this water has been allocated, the perennial water-supply question gets distilled to, “Will McPhee fill this year?”

The answer for this year is yes, even though the current run-off prediction is less than half of the long-term average. This is because the reservoir was more than half full at the beginning of the water year. Since the reservoir started with 132,000 acre-feet, it only needs about 100,000 acre-feet of inflow to fill.

Past water shortages were not as well-timed. According to the Dolores Project Drought Contingency Plan, low carryover in McPhee Reservoir combined with lower-than-average inflow resulted in several years of reduced water allocations.

Mike Preston, DWCD’s general manager, highlighted this recent pattern when asked about his concerns regarding this water year. “Our primary focus in 2018 is meeting Dolores Project allocations,” he said. “If allocations are shorted, we have drought-plan measures to manage drought-induced shortages. The big concern is 2019. Even if we make 2018 allocations, we will end the water year very low in the reservoir and totally dependent on 2018-19 snowpack.”

Who is vulnerable?

The effects of this year’s water shortfall will vary greatly, depending on irrigation district and water demand. As noted earlier, irrigators dependent on McPhee Reservoir such as DWCD full-service irrigators and Montezuma Valley Irrigation Company (MVIC) users have better–than-even odds of getting a full water allocation this year.

However, irrigators dependent on other water-storage facilities with less capacity and carry-over, such as the Summit and Mancos irrigation systems, could experience serious shortfalls. Unless there is a miraculous change in the weather pattern and it rains whenever needed, reduced irrigation means reduced agricultural production.

Nina Williams, owner and operator of Haycamp Farm and Fruit, relies on irrigation water from the Summit system. She is expecting about 30 days of irrigation water this year.

Because she uses drip irrigation for her vegetable farm and fruit trees, she is not planning to reduce her market farm production. But she faces hard decisions in managing her herd of heritage beef cattle.

“I am more concerned this year about pasture and hay,” Williams said. “I will have reduced pasture and therefore have to lease additional pasture and incur additional livestock transport and management costs to keep the animals rotated on what could be sparse pasture. And local irrigated hay will also be in short supply and high demand. In the end, I will have to travel further to get hay and the cost of hay could very well be higher this year.”

This year, the most vulnerable water users could be those that rely on the river itself, such as wildlife, particularly trout below McPhee Dam. The drought plan includes an example of the impact of the 2013 year. Because the water allocated for fish is also shorted during drought years, in 2013, low flows in the river below the dam reduced the density of trout in the river by two-thirds, to 5 pounds per acre – well below the 60 pounds per acre required for Gold Medal status. The Dolores River reach between the dam and Bradfield Bridge held this coveted status for the first decade after the gates on the dam were closed.

Thriving during drought

There are a variety of strategies that agricultural water users and backyard gardeners can use to reduce water demand and keep growing during a drought. The drought plan, while not being implemented this year, is designed “to describe ways to increase carryover storage in McPhee.”

Preston noted that measures in the plan are already being implemented. “Dolores Project farmers have made substantial gains in on-farm efficiency with more efficient center-pivot sprinklers being installed with the help of High Desert Conservation and NRCS,” he said. “There are also specific experiments under way with alternative sprinkler-nozzle packages. MVIC is also making on-farm efficiency gains via center pivot installations and has made substantial delivery system efficiency improvements in recent years.”

Bob Bragg, a specialist in local agriculture, has advice for farmers considering fallowing a field because of irrigation shortages. “The best strategy is to plant a cover crop such as annual rye grass that will protect the soil and combat weeds.” Bragg said annual rye grass, Lolium multiflorum, is a cool-season grass that can be planted early in the spring, harrowed in, and with a couple of light irrigations, will usually produce a dense cover that can even provide some forage if it gets a little rain.

“If it starts to grow, then dies because of lack of water, it will still prevent wind and water erosion,” he said.

For backyard gardeners, Bragg recommends focusing on getting water to a plant’s root zone rather than sprinkling it on the surface. “The depth of the water infiltration can be measured with a simple soil probe. Soil probes have a round tip that make them difficult to push into dry soil, but easy to push into wet soil. For example, when the probe is pushed into the soil of a lawn, or grass pasture, and it goes in about 8 inches before running into harder, drier soil, the soil profile of the grass root zone is saturated, but water has not been wasted by going below where the roots can uptake the water.”

Without any realistic prospects for a boating release from McPhee this year (unlike the 60-day boating season enjoyed last year), Amber Clark, executive director of the nonprofit Dolores River Boating Advocates, reports that they are focusing “on the ground” this year.

“DRBA is formalizing relationships with federal government agencies including the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management to partner on management efforts in the Dolores River corridor such as campground cleanup,” she said.

Despite the lack of boating releases, the group plans to fulfill its commitments to its youth programs by floating on the Dolores River above the dam, although scheduling these trips as well as the popular raft-rides at the annual Dolores River Festival in early June will be difficult this year. Predicting when Dolores River flow rates will be high enough to flow a raft is a whole other game.