Rosa Sabido, who has been living in sanctuary in the Mancos United Methodist Church since 2017, shows where she kisses the hands of a statue of the Virgen Guadalupe that belonged to her mother. Photo by Janneli F. Miller

In mid-February, Rosa Sabido will mark her 600th day of living in sanctuary in the Mancos United Methodist Church.

What does it mean to live in sanctuary? And why would someone make a choice to do such a thing?

The church accepted Sabido on Friday, June 2, 2017. She is there because she does not want to be deported, something which is happening to people who check in for routine appointments with ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement).

Sabido, who speaks perfect English, was born in Mexico, but has spent most of her life in the United States, arriving in 1987 at age 23 for the first time, to visit her parents. She obtained a visitor visa.

Her mother, Blanca, who had divorced Sabido’s biological father when Sabido was ten, came to the United States in the early 1980s, and married Roberto Obispo, an agricultural worker living in the U.S. as a lawful permanent resident in Cortez. Obispo became a U.S. citizen in 1999, and filed papers that allowed Blanca to become a citizen in 2001. However, at that time, immigration law did not allow Sabido to be included as a family member.

When people hear about Mexicans living in the U.S. or seeking sanctuary to avoid deportation, many ask, “Why don’t they follow the laws and become a legal citizen?” But the pathway is often arduous, even impossible.

Sabido, now 53, wants people to know she is not a criminal. She has been trying to follow the complex immigration laws and become a legal U.S. citizen for more than 20 years. During that time the laws and regulations have changed, with each change bringing a new set of procedures to comply with.

Joanie Trussel, a supporter and media contact for Sabido, explained, “She did do it legally! She has been spending $5,000 a year on lawyers for at least four or five years. She did do what she was told to do, but she still is unsafe.”

Trussel said Sabido sought sanctuary because her lawyer told her, “If you show up to your stay-of-deportation interview, you’ll probably be deported.”

“ICE has been deporting people in Durango,” Trussel said. “They have no mercy. They show up, find people and deport them. It’s such a contrast to the idea that this is the land of the free and home of the brave.”

Craig Paschal, pastor of the Mancos United Methodist Church, said that Sabido’s case “points to a broken immigration system.”

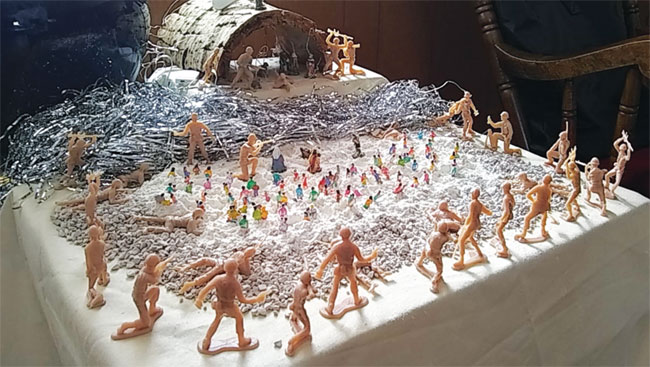

Rosa Sabido created this work depicting an image of the U.S.-Mexico border in which the people (immigrants) are surrounded by police/ICE while there is a Nativity scene in the background. Courtesy photo

He said his congregation of around 100 decided to become a sanctuary before they knew of Sabido’s situation because sanctuary fit within the tenets of their beliefs, starting with the idea of loving your neighbor.

“All human life has value and dignity and worth,” said Paschal. Other values include the idea of common humanity, and the notion of building a “beloved community.”

Paschal cited the Pledge of Allegiance, which ends with the words “with liberty and justice for all.” He noted that it doesn’t say liberty and justice for some.

The congregation was well aware of the increasing tension around immigration and had identified perhaps 12 to 15 families – all long-term members of the community – who could perhaps be at risk of deportation due to the changing regulations and shift in cultural attitudes. Paschal said becoming a sanctuary was a result of the congregation’s commitment to their beliefs. “It’s living out our values,” he says.’

Pink hands

Sabido spends her days in the Fellowship Hall of the church. Every day she kisses the hands of a statue of the Virgen Guadalupe. Now, she points to show how her lipstick has tinged the praying hands pink. The statue belonged to her mother, who died in June 2018 at age 71 from complications of cancer surgery.

Before becoming ill, Sabido’s mother visited daily, offering her daughter support and companionship. When she was diagnosed with cancer, Blanca travelled to Mexico for her medical care, which for her was easier to obtain and more affordable than in the U.S. However, this meant that Sabido could not be with her mother during her medical treatment, nor could she attend the services when she died.

“I asked if they could bring me the statue of the Virgen,” Sabido said. “I always go to it every day. I kiss her hands and I kiss her lips.”

Leading by Example

Sabido, a devout Catholic, feels that God has placed her in her current situation in order to help others in a similar plight. She is not married, and this gives her the freedom to devote her energies to other things.

Rosa Sabido keeps these dried flowers from her mother’s funeral in her room in sanctuary because she wasn’t able to attend the funeral in person. Photo by Janneli F. Miller

“I believe that destiny put me in this place so that people can learn better who we are. I know that many Mexicans don’t have the fuerzas [strength] to teach more about Mexican culture – they don’t want to. But I can teach them or lead by example,” she explained.

Sabido has helped organize vigils to mark every 100 days of her time in sanctuary. Most recently she helped plan a posada, a Mexican tradition reenacting the Biblical story of Joseph and Mary’s journey to Bethlehem and search for shelter there. The word posada translates as “inn” and in Mexico is usually celebrated for the nine nights before Christmas with processions, songs, and candles.

In Mancos the recent posada, held on Dec. 21, consisted of a procession leading from St. Rita’s Catholic Church to the United Methodist Church, where participants shared a meal. “Lots of people came, and they didn’t know what a posada was,” Sabido said.

“Joseph and Mary were refugees, looking for housing. It’s up to me to put forward this perspective of what happened then and what we living now. It is exactly the same.”

Sabido becomes animated when she describes how the events she helps to organize help local residents understand more about Mexican culture.

Last November, she reached 500 days in sanctuary.

“We did a Day of the Dead altar, so that the people know why we did it. The meaning of the Day of the Dead is a lot deeper than what you see on the tele. We showed the milagros that are miracles, so that they can learn, and valorize our traditions.”

She said she understands that there are American traditions such as Thanksgiving, “but they don’t know our customs. I want to provide a deeper meaning. Christmas is not only about the presents – Joseph and Mary were looking for lodging, refugees just like us.”

Her sentiments and activities are a fundamental part of what it means to live in sanctuary, and Sabido’s faith gives her the strength to continue. She said that, yes, every day she could become depressed, but she is committed

to helping others. It’s not just about her. She believes it is her mission to educate others about her country, her culture, and her plight.

Beadwork

The contemporary sanctuary movement consists of more than 800 faith communities organizing in order to protect and stand with immigrants facing deportation. Locally, community members are offering support, helping Sabido by going shopping for her, or coming by the church to give her acupuncture, massage, chiropractic treatments, or even a yoga session.

Every week women from Lewis and Mancos come by to sit and do beadwork with Sabido. One of these women, Betty Schneider, explained, “We moved our beading group here so we could be with Sabido. She is good company and we enjoy her.”

The beaders emphasize that they don’t ask Sabido about her plight because their intent is to provide friendship. They don’t feel a need to discuss her situation, but instead pass the time in creative expression, laughing as they make earrings, necklaces, and ornaments.

The decision to enter sanctuary was voluntary. Sabido wants people to know that she is not being detained. But she added, “I don’t have freedom – this does not exist. Not here, not outside.“ She is also not hiding. In addition to articles in local papers including The Journal and Durango Herald, she has received national press coverage in the Washington Post, L.A. Times, Boulder Weekly and on digital news sources including aol.com and CNN.

‘I’m a target’

As long as she stays on the church grounds she is protected by the 4th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which limits government searches and seizures on private property. ICE agents cannot enter the Mancos United Methodist Fellowship Hall without a warrant.

However, if she steps outside of church grounds she fears she could be picked up and deported. She has no idea if ICE agents are watching her.

One result of this is that she does not receive visits from any of her Mexican friends.

“One time they came here, but now I think perhaps they are afraid,” she said. “They know that I’m a target, and they’re afraid. But I know that they support me, from the Catholic church.” Sabido spent eight years as a secretary for the Catholic church in Cortez before coming to sanctuary.

“I want people to know I’m still here. I will not give up. It is important that people know I am here, 18 months now. I continue.”

“She is in this limbo,” said Trussel. “And this limbo is really difficult, after a year and a half.”

Sabido, wearing clothes that Trussel bought for her, and cooking food in the church kitchen for herself and for community events, is a bright and energetic woman. She has dedicated herself to transforming personal trials into educational efforts. She hopes that raising awareness about the cumbersome and dysfunctional immigration system will lead to better circumstances for others.

“I am here. I will not give up. My work can help others,” she said.