Philip Kerr died young – too young – in March of 2018. He was the author of more than 40 books, works of both fiction and nonfiction that include his Children of the Lamp middle-grade novels (as P. B. Kerr) and his popular Scott Mason thrillers. But it will be for his Bernie Gunther series of historical detective novels that Kerr, a Scotsman by birth, will forever be remembered, and lionized, as one of the greats of the crime fiction genre.

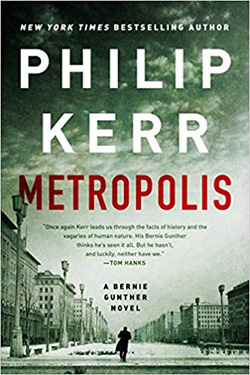

I first encountered Bernie Gunther while reading Jane Kramer’s 2017 profile of Kerr in The New Yorker (“The Third Reich’s Good Cop”) and promptly purchased the first three books in the series (March Violets, The Pale Criminal, and A German Requiem), all published between 1989 and 1991 but reissued by Penguin in 1993 in a single volume titled Berlin Noir. After writing that trilogy, Kerr pursued other subjects until resurrecting Bernie in 2006 with One From the Other. Ten more Bernie novels ensued in rapid succession, a stunning oeuvre that includes such personal favorites as If the Dead Rise Not (2009), A Man Without Breath (2013) and The Lady From Zagreb (2015). And then, at the height of his growing renown, Philip Kerr unexpectedly succumbed to bladder cancer at age 62. But not before penning Metropolis, Bernie Gunther’s 14th and final jaunt through the seedy underbelly of Nazi-era Berlin.

I first encountered Bernie Gunther while reading Jane Kramer’s 2017 profile of Kerr in The New Yorker (“The Third Reich’s Good Cop”) and promptly purchased the first three books in the series (March Violets, The Pale Criminal, and A German Requiem), all published between 1989 and 1991 but reissued by Penguin in 1993 in a single volume titled Berlin Noir. After writing that trilogy, Kerr pursued other subjects until resurrecting Bernie in 2006 with One From the Other. Ten more Bernie novels ensued in rapid succession, a stunning oeuvre that includes such personal favorites as If the Dead Rise Not (2009), A Man Without Breath (2013) and The Lady From Zagreb (2015). And then, at the height of his growing renown, Philip Kerr unexpectedly succumbed to bladder cancer at age 62. But not before penning Metropolis, Bernie Gunther’s 14th and final jaunt through the seedy underbelly of Nazi-era Berlin.

Before getting to Metropolis, a word or two about Bernie. He’s a homicide detective in mid-century Germany, which places him in the awkward position of investigating murders under the auspices of a government itself run by genocidal murderers. The irony of that situation, and its attendant moral ambiguities, are not lost on Bernie, who’s every bit as smart and sardonic and world-weary as his more familiar American counterparts, Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe. While not himself a Nazi, he takes his orders from various Reich ministers, which he follows or not as his conscience dictates – a state of affairs that frequently leads both to professional jeopardy and personal redemption.

The Bernie Gunther novels are nonsequential, meaning one might find Bernie as a wartime SA officer working for the Gestapo and the next as a postwar private detective hunting the very criminals whose dictates he’d followed, or thwarted, as circumstance had required. And like those of Hammett or Chandler, Kerr’s stories can be densely complex, with a dizzying array of colorful characters. What they all share, however, is scrupulous historical accuracy – the books are chockablock with real people and true events – and the kind of immersive atmospherics that, after reading a few, will leave you feeling like a Berlin native.

Metropolis, then, is both a valedictory and an origin story. The novel opens in 1928, in the waning days of the Weimar Republic, when Berlin is a virtual Babylon of artistic and sexual freedoms. Bernhard Weiss, a Prussian Jew who heads the city’s Police Praesidium, recruits vice detective Bernie Gunther to join Berlin’s elite Murder Commission even as a rash of sadistic killings is terrorizing the city’s prostitutes. Worse, the killer is baiting the Murder Commission by leaving clues at his crime scenes and sending taunting letters to the press.

Bernie’s efforts to succeed in his new assignment will include posing as a legless war veteran, frequenting several of Berlin’s more notorious hotspots, and teaming with one of the city’s most infamous gangsters. But with anti-Semitism already rampant and Nazism close on the horizon, he’ll soon conclude that the murderer’s true agenda is more complex than meets the eye.

Like its predecessors, Metropolis ($28, from Marian Wood/Putnam) contains scenes of violence and sexuality that make it inappropriate for young readers. For the rest of us, it’s a fitting introduction – or farewell – to one of the greatest protagonists in all crime fiction.

Chuck Greaves is a member of the National Book Critics Circle whose sixth novel, Church of the Graveyard Saints (Torrey House), will be in bookstores in September. You can visit him at www.chuckgreaves.com.