To Montezuma County writer David Feela, poetry bursts with emotion — the kind that explodes from the heart and imagination.

“Prose is beer. Poetry is whiskey,” he says. Feela has just brought out his first full-length book of poetry, ‘The Home Atlas,” a print-on-demand volume published by Word Tech Editions.

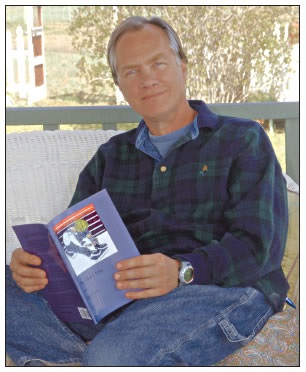

David Feela, a prolific poet and freelance writer living in Lewis, Colo., has just published his first full-length book of poetry, “The Home Atlas.” Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

“It’s 72 pages long and took 35 years to write,” he explains. “I mean, there are poems in there from when I was still in college, all the way to recent times. It’s truly an atlas of where I’ve been.”

He’s been all over. “The Home Atlas” explores compass points from the esoteric to the humorous.

Asked to select a poem to discuss, he chooses “A Marriage Counselor Discusses Adam & Eve,” calling it a genesis for the book, and a modern understanding of the Bible.

Her initial complaint

was based on a lack of choice,

a resentment she harbored

until the day she died.

Adam, after all, was

the only available man.

She took him for better

but felt she got all the worse.

He didn’t share her grievance.

In fact, he couldn’t believe his luck.

He awoke from a nap

to find his first woman

naked and toting lunch.

Naturally, Adam wasn’t perfect

but he went on and on

about the snake,

as if Eve was the cold-blooded one.

And truth be told,

Eve liked the snake,

maybe even better than Adam.

Thought it at least understood

how to have a conversation.

In the end, of course, it was

a beginning.

The two reconciled, had kids,

went into business together:

Paradise Tours.

All their customers wanted to buy

a few acres and build

but in Eden the covenants were explicit:

no people.

Unusual points of view and quirky images fill many of the other poems in ‘The Home Atlas.” Take “Lifeboats” on pages 45 and 46.

I’ve been thinking about being rescued

from my life, relying on someone else

to figure out what I need.

I’d be willing to wait a while longer – if I have to –

for the right kind of person

but he or she had better be

quicker than the last fifteen years.

I’ve also been thinking about staying put

so someone can find me,

like the survival books recommend,

not wandering in circles

only to find myself back where I started.

I’d build a fire

if I had some matches,

maybe do some light reading

until the night grew too dark to see.

By the time the stars made an appearance

I’d hope the one I’ve been counting on

will have noticed the smoke,

wrapped me in a blanket

and helped me to a clearing

where my future will be anchored

like a cruise ship

with a buffet that’s always open

and a horizon full of ocean

to suggest a backdrop of adversity.

“There is that sense of sometimes you have so much going on in your life that you wish someone else would take care of it,” he muses.

Not only that. Who would thing of a lifeboat as rescuing a person from life?

Feela thinks his word connections arrive from his perceptions of situations as well as from their reality. “There has to be something of truth . . . so people can shake their head and say, ‘Yeah, that’s exactly what it is.’”

Geography helps define that truth: The Minnesota farm where he grew up, St. Cloud State University where he got his education, and Southwest Colorado, where he spent the last 27 years teaching at Montezuma-Cortez High School.

In the verse “1965,” he recalls how he felt as a child sitting at Sunday dinner. The adults talked. He listened — and thought.

On racial tension my father said,

“You don’t put a cow

in the same stall with a horse “

The table smiled and nodded,

took a warm-up in its coffee cup,

dug into a deep bowl of ice cream

and said, “Yup,

sure is going to be

a hot one this summer.”

I sat listening—maybe twelve—

at the edge of myself,

staring at their hands

like they were scoops of trouble:

one with liver spots

the size of sugar babies,

one with chewed nails,

fingers of ringed gold;

another with knuckles cobbled

like a handful of dice,

white as ivory.

Silver spoons clattered

against china bowls

and I was afraid to move

for fear they would notice

the unwashed part of me

out of the shallow part

of those deep bifocals, turn on me,

and pull me from my chair.

I glanced at my hands hanging limp

as evening primrose blossoms

before the cool night comes on,

and I knew these hands didn’t belong,

not here. I saw how the raspberries

left a streak of blood in every bowl,

how nothing that was white

would stay just white anymore

Feela does his best writing in the morning, before the day’s distractions start. He does not set out to develop a poem, an image, or a connection, but jots down ideas, then plays with what he’s written, as if he were doing a puzzle. “Suddenly when you see a solution, you see your mind lean toward what the answer is.”

He admits that many failed poems inhabit a box in his barn. “You’ve got to go through the stupid ones to get to the good ones.”

Instinct tells him when he’s written something good. So does his wife, Pam Smith. She’s his “front line” editor, whose judgment he trusts completely.