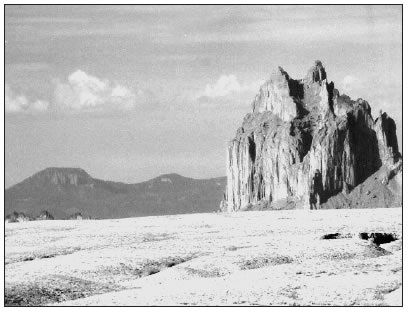

Ship Rock, a legend of Navajo culture and a classic local landmark, has become shrouded in a veil of industrial smog.

The 1,700-foot sentinel rising from the northern New Mexico desert has for generations been a part of the breathtaking view from surrounding areas. Its craggy shape is a symbol of clear skies, clean air and good health. But in recent years, pollution from New Mexico power plants, increased traffic, and the booming oil and gas industry have obscured the view of Ship Rock, or wiped it out completely. As the smog accumulates, prevailing winds push the foul air northward into Southwest Colorado and beyond, prompting a health controversy that crosses political lines and geographic boundaries.

Ship Rock, the craggy sentinel that gave Shiprock, N.M., its name, and is the most identifiable landmark for miles around, is increasingly obscured by regional haze. Colorado State Rep. Scott Tipton has called for New Mexico to force the Four Corners Power Plant to reduce emissions that drift into Colorado. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

“Just as New Mexico would not accept toxic pollutants to be dumped by Colorado into the Rio Grande river, neither should Colorado allow avoidable pollutants to flow into our state from New Mexico,” wrote Scott Tipton, a Republican Colorado state legislator, in a March 17 letter to Interior Secretary Ken Salazar.

In the letter, Tipton, along with Colorado Attorney General John Suthers, urged Salazar to clean up the Four Corners Power Plant, located on the Navajo Nation, whose “excessive emissions have traveled across state and sovereign lines, clogging the air and damaging the health of Southwestern Colorado residents.”

Tipton pointed out that the plant’s emissions are the largest single source of nitrogen oxide, a major component of smog, in the United States. Furthermore, it “has been expelling pollutants in significant excess of comparable coal-fired power plants for the past several decades. For example, the FCPP produces over three times the nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions as the Coronado power plant in Arizona,” he wrote in the letter.

Ozone, a colorless gas, is a secondary pollutant created by a chemical reaction in the atmosphere where the sun heats up volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides, a byproduct of burned fossil fuels. Ozone is a known health hazard that can cause asthma, damage lung tissue, increase risk of the heart attacks and lead to premature death.

‘Something strange’

Air-quality monitors are sited throughout the Southwest to detect levels of ozone in violation of the federal Clean Air Act. Once a monitor detects ozone levels above 0.075 parts per million, the area is given nonattainment status, which triggers a flurry of often-expensive corrective pollution measures.

But when non-attainment levels occurred at a monitor at Navajo Lake last October, “something very strange happened,” said Mike Eisenfeld, New Mexico energy coordinator for the San Juan Citizens Alliance, an environmental watchdog organization based in Durango.

Shortly after ruling the area was in violation of the Clean Air Act, the New Mexico Environmental Department reversed its decision, claiming the monitor had malfunctioned. The Navajo Lake data, which averaged at .077 ppm for an 8-hour period, was thrown out and fresh readings with a newly installed monitor showed the area was barely in attainment at .075 ppm.

“They said that a solenoid was malfunctioning, but can’t that be an argument that anyone could use at any time?” Eisenfeld argued. “How does a community address that . . . where perhaps industry influence played a role.”

Lack of good-faith cooperation among the energy industry, regulatory agencies and public-health advocates regarding air quality is a concern and fuels suspicion, he said. When the monitor’s data was determined to be invalid, “a new one was installed with a couple of industry guys out there doing the analysis, and when we protested that we weren’t invited they said it was an inadvertent oversight. That’s unacceptable.”

On March 12, Mary Uhl of the New Mexico Department of Environment informed the Four Corners Air Quality Group of the change in ozone status. In an e-mail, she wrote:

“The NMED and the EPA are currently conducting a joint investigation into the validity of the data; however, at this time, there is substantial doubt that the data is valid, particularly data collected in October 2008 that would indicate that the area would not attain the federal ozone standard. Due to this recent development, the state of New Mexico will not recommend ozone non-attainment status for San Juan County and part of Rio Arriba County, as was previously posted on our website.”

Uhl explained that an extensive audit of the monitors at the Navajo Lake site, conducted on March 4, showed the site “recorded levels of ozone that did not appear to correlate with levels of ozone recorded at other monitors in the region.” She added the suspected faulty monitor and an additional monitor installed at the site passed an initial performance test, “however, shortly after the audit a problem was identified with the subsequent monitoring data collected.”

Eisenfeld says proper oversight of the monitors needs improvement; otherwise it threatens the validity of certified ozone data in court.

“In our neck of the woods, the energy industry has a lot of influence, and you’ve got to predict that somebody will want to challenge that the data is verifiable,” he said, adding that it is not uncommon for ozone monitors to spike like the one at Navajo Lake. In Pinedale, Wyo., for example, a monitors had spikes of 0.120 ppm.

“But whether the ozone level is 0.077 or 0.075, it is still a huge problem,” Eisenfeld said. “Our area ozone levels are comparable to major urban centers like Denver, Dallas, Houston and Phoenix. There is a very high probability that (non-attainment) will happen again in our area within the next two years.”

Studied to death

For Tipton, now is the time to act on cleaning up regional pollution.

“We have a problem, and I don’t need another study to tell me that I can no longer see Ship Rock because of all the haze,” he said in a phone interview. “Those power plants are producing energy for New Mexico, Arizona, California and Nevada. So they get the juice, and we get the junk.”

He suggests more investment in technology to improve air quality, such as installing scrubbers on power plants, and advancing alternative energy such as solar and wind.

“But with (alternative energy) we don’t have the technology available yet to maintain our energy needs,” Tipton said. “This country has a huge abundance of coal reserves, so I think the incentive is to use it, but do so more cleanly. With the stimulus package, maybe we can create a costshare program to improve power- p l a n t emissions. That would be a win-win situation to help clean up the environment and provide energy.”

Tipton contends that the EPA has been arbitrary in the way it evaluates and enforces air-quality standards in the country.

“I get weary of the attitude that rural America isn’t worth as much as urban American, that somehow we can afford to pollute more here,” he said. “Our people, our quality of life, our water and air are every bit as important as in New York or anywhere else. It is time to push this agenda aggressively.”

Killer ozone

A study of ozone published in the March edition of the New England Journal of Medicine shows long-term exposure to the gas is more lethal than previously thought.

The study, which spanned 18 years and involved half a million people, showed that even low-level exposure to ozone can be fatal. The EPA has reported it is reviewing ozone standards, and may impose stricter regulations in light of the new medical evidence, reported the Los Angeles Times.

The newspaper noted that 345 counties nationwide are in violation of ozone standards, potentially affecting more than 100 million people. Michael Jerrett of the University of California at Berkeley, coauthor of the study, concluded that ozone exacerbates respiratory conditions already responsible for some 240,000 U.S. deaths per year. People with conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema and pneumonia are most affected, according to the study.

“Clean coal” is aggressively being promoted under a $45 million ad campaign, but there is no such thing, according to Larry J. Schweiger, president of the National Wildlife Federation.

In an excerpt from his upcoming book, published in the organization’s magazine, Schweiger warns of the health dangers of burning coal. Mercury is a particularly dangerous emission from coal-burning, especially for children.

Schweiger cited a study by the University of Texas Health Science Center that links mercury exposure to higher rates of autism in children. The study found that for every 1,000 pounds of mercury released by power plants in Texas, there was a corresponding 3.7 percent increase in autism rates at local school districts.

“With increases in coal-burning and mercury in the human environment, there should be little wonder why autism is the fastest-growing developmental disability, increasing annually by 10 to 17 percent,” wrote Schweiger.

Another danger of coal pollutants is increased radiation exposure. In a study published in Science, neighbors of coal-fired power plants were found to be at a higher risk of radiation exposure than neighbors of nuclear power plants.

In the end, public awareness, stricter pollution controls and political pressure to protect human health are the keys to improving local air quality, said Eisenfeld of the San Juan Citizens Alliance. There is a definite down side to violating the Clean Air Act standards, he said, not just for public pride and scenic views, but for industry as well, which would be forced to cough up millions of dollars for technological improvements under the law.

“The people of the Four Corners should be irate,” said Eisenfeld. “Why should one of the most remote and beautiful parts of our country be sacrificed for cheap power and revenue? Everyone wants to pretend that the air quality here is fine, but it is not.”