A decade after she became manager of Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, LouAnn Jacobson is finally getting a chance to enjoy the backcountry of the enormous, rugged landscape west of Cortez.

That’s because she retired Oct. 1.

LouAnn Jacobson has retired from her position as manager of Canyons of the Ancients National Monument. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

Until then, she had little time to explore what is one of the nation’s premier areas set aside to protect ancient cultural resources.

On her final day, she went for a hike, she said. “I wasn’t going to spend my last day in the office. I hiked to an archaeological site I had never been to before. It was a beautiful day.”

Ten years of hard work marked by periods of controversy and criticism have not changed Jacobson’s love of the 170,000- acre, BLM-managed monument, which was designated by President Bill Clinton in June 2000 over the stormy objections of many local citizens concerned about restrictions the new status would bring.

“One of the things that I want to do now that I have more time is explore a lot of backcountry, having that same sense of discovery that the public has. I have never lost that excitement of finding an archaeological site or seeing artifacts on the ground. I still have the little-kid approach.”

Many delays

Jacobson has been the monument’s first and only manager so far. (Heather Musclow is acting manager since her departure.) She served as interim manager for five months immediately following the designation, then was named to the permanent position.

“When they were getting ready to advertise the job, I decided – after months of saying I didn’t want to do this permanently – that I was emotionally and mentally invested in what was going to happen. So I sort of made the conversion that this was something very important to me and something I wanted to do.

“I started out with a certain level of trepidation of what I was getting into, but ultimately I’m really glad that I spent my last 10 working years doing this. It was an incredible experience.”

The experience had its ups and downs, of course. One of the most difficult tasks – and one of the main causes of criticism leveled at Jacobson – was the process of getting a management plan in place. That process took 10 years.

“Never did I think it would take so long to get the plan done,” she said. “Never in my wildest dreams and/or nightmares.” She said the BLM generally expects resource management plans to be completed in about three years. Because of bureaucratic delays, it took almost two years just to get the notice of intent to start the process published in the Federal Register, she said.

“That should have been a sign of what was going to happen.”

Part of the subsequent delay was the result of the high level of public interest in the plan, she said.

“The agency’s expectation, and it’s the proper one on some level, is that there be a lot of public involvement and public meetings,” she said.

“But the expectation of having all this public involvement and doing it in three years is pretty unrealistic.”

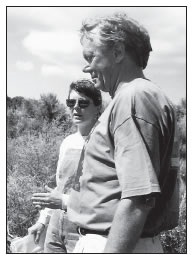

LouAnn Jacobson shows then-Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt around the Lowry Ruins in 2000, before Canyons of the Ancients was made a national monument. Photo by Gail Binkly

The BLM decided to form a monument advisory committee, and didn’t want to start the planning process until those individuals were chosen, so that further slowed the process. The openings had to be advertised in the Federal Register and the committee members had to be appointed by the secretary of the Interior after a selection process.

Then the contractors the BLM had hired to handle writing the plan turned out to be a disappointment, Jacobson said. “We ran into problems with unsatisfactory performance and escalating costs. My decision to terminate those contracts, which is pretty unusual, also led to delays.” New contractors had to be hired and brought up to speed, she said, but in the end the change “certainly saved the government money – potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

The plan was finally approved in June of this year, despite appeals filed against it by about a dozen parties, including Montezuma County. The current commissioners have been vocal critics of the monument, saying it imposes too many restrictions on livestock-grazing and oil and gas extraction.

Jacobson said the level of scrutiny and controversy, however, has not always been so high. “For awhile the local scrutiny actually diminished, and I would credit the monument advisory committee. They were meeting almost every three weeks and identifying the issues that were of concern to them. This provided an opportunity for the public to express their concerns, to talk to the advisory committee and BLM in an open forum. Those meetings and discussions helped to bring the level of concern down a bit.

“Along the way, [then]Secretary [Gale] Norton sent a letter to local governments and asked if they wanted to do something about the Clinton monuments, and the Montezuma County commissioners at that time sent a pretty complimentary letter back, talking about the committee.

“It’s only been in the past three or four years that some of the controversy has risen to the top again, particularly around some of the issues about oil and gas, and grazing.”

Now that the plan is in place and a logjam over a proposal to drill carbon-dioxide wells in an area with high cultural-site density has been broken, Jacobson hopes the controversy will subside again.

“I think we’ve demonstrated on the oil and gas side that we’ve set the tone to move forward with some pretty complicated projects,” she said. “Kinder Morgan [the CO2 company] hung in there for the time it took to work it out. They addressed our concerns and we learned how not to do things. Mistakes were made on both sides and we figured out how to resolve those. But along the way the commissioners were expressing concern about what we were doing and how long it was taking.”

Jacobson said she now gives a presentation to land managers about the Kinder Morgan project and how the issues were worked out.

Managing Canyons of the Ancients has always been tricky, Jacobson said, because of “the juxtaposition of really high cultural resources site density and fluid mineral leasing.”

The monument is part of the BLM’s decade- old National Landscape Conservation System, a collection of some of the country’s most spectacular public lands.

“Every area in the system has unique qualities,” she said. And each landscape has different issues. “The ones in Arizona are seeing horrific problems with illegal immigration, people tramping through the desert,” she said. “Other areas have more conflicts with grazing than we do. I’m thankful for many of the things I don’t have to think about.”

Canyons’ special concern, of course, is pot-hunting – the illegal looting of ancient artifacts. “It comes and goes, but right now it seems like pot-hunting and vandalism is on the upswing,” she said. “Our law-enforcement officers have their hands full. We’re lucky that we have two full-time law officers and a third to help, but with 170,000 acres, [catching offenders] still means being in the right place at the right time.”

There have been successes in recent years in nabbing pot-hunters, she said, but getting the cases through the court system remains a challenge. “There have been some disappointing sentences coming from the 2009 Blanding actions [that resulted in the arrests of 24 people for pot-hunting-related charges],” she said. “It’s still difficult getting people in the courts to understand that there is harm in these crimes, that they’re harming the Pueblo people and the Native Americans living today. It’s very emotional for them. And looting means the loss of opportunities for research and science and future generations.”

More people, more rules

Jacobson said she believes conflicts over public-lands management will intensify in coming years.

“More and more people are seeing public lands as a place to recreate, so it’s the lovingto- death syndrome. Unfortunately, some of the impacts that come with the increased interest result in more regulation. You see all the issues arising with travel management with the Forest Service – it’s occurring on the BLM side too. There are so many usercreated roads that are duplicative and are impacting resources.

“The interest in public lands is going to increase as people seek respite in the backcountry from urban intensity and busy lives.”

Another huge issue facing public lands, she believes, is the spread of invasive species and their impacts on native species and natural resources.

“I think those were the two top priorities we were looking at in implementation of the RMP for Canyons.”

Jacobson’s philosophy as manager was to keep most of the monument fairly rugged and undeveloped. “I think the outdoor-museum concept is working pretty well for us.

“The day after the monument was established we sat down and thought about, where are we going to send people that want to come here? We picked places the BLM had already been sending people to – Painted Hand, Lowry Ruin, Sand Canyon Trail, Sand Canyon Pueblo – and the next 10 years we stuck with that really, really close.”

Volunteers and staff at the Anasazi Heritage Center, which is the administrative center for the monument, have become good at matching visitors with appropriate destinations, depending on the vehicle they drive, how fit they are and how much time they have. Visitors are urged to stop at the Heritage Center first to get information about trails and sites, as well as the “Leave No Trace” ethic.

Changing the name of the Heritage Center (“Anasazi” is considered an outdated and somewhat offensive term) was something Jacobson never had time to do. “We had other things to deal with first,” she said. But some day a new name will be chosen.

In addition to finally getting a plan in place, Jacobson is proud of having helped to establish solid relationships between the monument and Native American tribes to enhance the center’s interpretation and education programs. Twenty-five tribes have affiliation with the monument, and there are close personal relationships with individuals from 10 or 12 of those tribes, she said. “Every time we get together with tribal elders I learn something new,” she said. “It’s a different way of thinking about things, and I think a better way.”

Another accomplishment during her term, she said, is the acquisition of approximately 7,000 acres of private land in parcels within or adjoining the monument. “As controversial as the acquisitions are on some level, we have worked only with willing sellers and have acquired some incredible archaeological sites – some of the most important sites in the history of Southwest archaeology. Those resources are now protected by federal laws and I think that’s very important.” Some key riparian areas have also been purchased, she said.

The volunteer program has been another success, she said. “We went from no volunteers on the ground to almost 250 people now, both with the Heritage Center and the monument. A lot of people deserve credit for that – the San Juan Mountains Association, the Elderhostel, the colleges.”

In the future Jacobson plans to be a volunteer herself, working mainly on projects outdoors.

“The volunteers set a great example for how to be retired,” she said, “and I intend to follow their lead.”