The search is on for a permanent superintendent at Grand Canyon National Park following the retirement last month of Steve Martin, who took over in February 2007.

Steve Martin retired recently after four years as superintendent of Grand Canyon. Photo by Cyd Martin.

Martin’s career began and ended at Grand Canyon, with positions there bookending a total of 35 years with the National Park Service. His efforts as superintendent were the capstone for his career – and the issues that commanded his focus are the most urgent and important challenges facing the world’s most famous natural wonder. As such, a look at Martin’s nearly four years at Grand Canyon serves as a “state of the park” address.

Stakes are high at the Grand Canyon. The superintendent and staff – currently 500 employees – must aim to appease the park’s myriad users, including hikers, campers, boaters, airplane pilots and the industries that capitalize on the park’s assets, like hydropower out of Glen Canyon Dam.

At the same time, they are under constant pressure from environmentalists, along with their own mission statement, to carefully safeguard the park’s natural resources. Their decisions are under constant scrutiny from more than 4 million visitors a year who hail from all over the globe.

With agency connections that stemmed from a two-year stint in the NPS’s Washington office, Martin was able to push forward several major initiatives that had been in the pipeline for years before his arrival, including resource management on the Colorado River itself and a new transportation plan that has already begun to alleviate crowding at the South Rim entrance station and ever-popular Mather Point. More will be revealed about Martin’s influence on other issues, including a backcountry management plan and new rules regulating air travel over the park. Both of those plans are expected to emerge this year.

Teamwork and elbow grease

Martin’s not shy about saying newfound energy came around on his watch, on thorny issues like overflights and Colorado River management.

Previously, “on many of these issues, there was almost no movement,” he said, adding that he brought experience both from his time in the NPS’s Washington offices and 32 years in the field, at parks including Yellowstone, Grand Teton, and Denali and Gates of the Arctic in Alaska.

But he also credits teamwork. The aspect of his time at the park he’s most enjoyed, he said, has been “developing and then getting to work with an incredible team of people – conservation groups, federal and state agencies, and employees in park believing they can get things done.”

In an interview just before he retired, Martin was most animated when he reflected on upgrades to the “horrendous” employee living and working conditions he found when he arrived post four years ago.

“Literally, there were trailers that were 30 years old that we would have employees in,” he said. “If you wanted to come here even as a permanent employee, you couldn’t bring your kids or your spouse or your dog.” He said new employees would sometimes live in shared housing for a year before they could move into a place with more privacy. And for some workers, office conditions weren’t much better.

“Our entire science division was working out of a garage that had been abandoned by our maintenance division seven years ago,” he said, adding that they suffered a leaky roof, mice and oil-stained floors with no carpeting. “To the credit of our employees, they stuck it out. But just because they’re willing to do it doesn’t mean you don’t take care of them.”

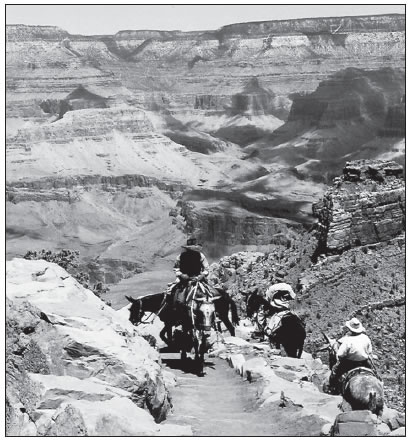

Mules carry visitors down the Kaibab Trail at Grand Canyon. Juggling the needs of the park’s millions of diverse visitors will fall to a new superintendent, as Steve Martin retired recently after four years at the helm. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga.

As such, one of Martin’s proudest accomplishments is remedying those conditions with measures including 64 LEED-certified green housing units under construction now.

And on Dec. 15, the park announced that its environmental assessment gave the green light to build a new science and resource management workspace in Grand Canyon Village. That new building is also being designed according to LEED certification standards and may include a rainwater catchment to irrigate vegetation, solar collectors to provide hot water for an in-floor heating system, passive solar to aid in building heating and cooling, and other energysaving features. The new construction is among the first at the park that’s incorporating cutting-edge energy-efficient design, including solar.

Challenges abound

Martin said he was surprised that he had to go to bat for the park on several fronts, fighting for recognition of the park’s worthiness for both funding and resource protection.

“Coming here I was … surprised that in some ways we were continually having to advocate for the Grand Canyon on a variety of fronts, when you would think people would understand protecting the canyon,” he said. Specifically, he thought it strange that some camps needed to be convinced of the value of flows out of Glen Canyon Dam to enhance the resources in the Colorado River.

“Here you have a law that says we’ll improve the resources of Grand Canyon by changing the way Glen Canyon dam is operated, without changing power production. It’s still difficult to get that done,” he said.

But he said it’s been fun to encourage every park employee to promote the park’s greatness, especially when he’s seen that it’s recognized around the world.

The canyon’s status as a world wonder is deserved not just because of its physical magnitude, he said, “but also because it’s so intimate. It’s truly a magnificent landscape, with worldwide constituencies. It’s humbling.”

And if that fails to impress would-be supporters or funders, he usually points out the park’s economic value.

“The park generates $750 million annually for the regional budget,” he says. “If you can’t buy into the fact that it’s a spiritual, biological and geological wonder, it’s good business too.”

‘Political risk’

Four years isn’t long, but Martin managed to build strong friendships and allegiances; it’s not hard to find people who will miss him.

“I’m just sad that Steve is leaving, just because he was the first super in a long time who had any idea of what the canyon is all about, and all the various communities within the canyon,” said Christa Sadler, a geologist and frequent Grand Canyon river and trail guide.

“The river community is usually the redheaded stepchild, and the river is often placed at a lower priority because it’s so far away from the rim. But his experience with the river allowed him to realize that it is the heart of the park, despite the fact that it’s not millions of people per year that see it. Who knows who we’ll get in replacement?”

Nikolai Lash worked with Martin as an activist on the ever-contentious issue of how to manage flows out of Glen Canyon Dam. As water-program director for the Flagstaff-based conservation group the Grand Canyon Trust, Lash represents conservation interests on the Adaptive Management Working Group, established in 1997 to guide the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in managing dam operations for both natural resources and power generation. It’s been an effort rife with conflict and even legal actions over the years. Martin stepped into the fray with courage, Lash said.

“All the main resources in Grand Canyon are in one way or another tied to sediment conservation,” he said. Science has long shown that high flows timed with sediment inputs create backwater channels where native fish thrive, build beaches and increase protection for cultural and archaeological sites. Subsequent steady flows out of the dam help to maintain those conditions.

“Steve recognized that dam operations needed to change, and expressed his beliefs when it wasn’t easy to do,” Lash said.

That’s because high and steady flows, while best for natural resources, diminish power production and hence revenue generated from Glen Canyon Dam, although not by as much as it was once believed. As such, “the politics of water and power dominated and continue to dominate at Grand Canyon,” Lash said. “He stuck his neck out when it wasn’t easy to do and said we need to accept diminishment of hydropower at Glen Canyon Dam.”

Martin’ efforts resulted in a high-flow experiment in 2008, with the backing of the Interior Department. And a new high-flow experimental protocol has been drafted for the future, with commitment by Interior Secretary Ken Salazar.

“It’s a change of operations at Glen Canyon Dam that happened in part because of Steve’s advocacy,” Lash said. “It’s not just words. And he did it with political risk, in a politically contentious environment.”

Moving on

Martin says his family won’t be jumping with both feet into retirement right away. His wife, Cid Martin, will keep her multiposition appointment as director of Indian affairs for the NPS’s Intermountain Region, superintendent of Canyon de Chelly and Navajo national monuments and the Hubble Trading Post.

He and Cid have ambitions to work with the international conservation community in Chile, Australia and Mexico.

“As you might expect, we’re outdoors people,” he said.

He said getting the overflights plan into a final draft will require work and public involvement.

“We really need to continue to be advocates for the restoration of the Colorado River,” he added. “It’s not a water issue. It’s a timing and flow issue.”

And taking care of the employees is something that is a constant, he said, along with continuing to adapt outreach efforts to changing times. That means adapting earth science lessons for the new, computer-savvy generation, he said, but being ready to educate them on how to survive outdoors once they arrive at the canyon.

“The work is never done,” he said. “You just sort of jump from the speeding train and hope someone else takes the wheel.”

In the short term, Jane Lyder, deputy assistant secretary for Fish and Wildlife and Parks for the Interior Department, has been named acting superintendent of Grand Canyon. She’ll assume her new duties this month.

Grand Canyon Roundup

Here’s a list of key developments at Grand Canyon that have marked the last four years of outgoing Superintendent Steve Martin’s career. Martin, who spent 35 years with the National Park Service, retired as of Jan. 1.

Employee housing: One of Martin’s proudest accomplishments is an $8.1 million project to build 64 employee apartments on the South Rim. The set of 8-plex buildings is expected to be finished next summer, and the park hopes they’ll be certifiable through the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification with a Gold or Platinum rating. The project will include construction of one and two-bedroom apartments, 96 parking spaces, utility connections, sidewalks and landscaping, construction of an access road, and the demolition and removal of several obsolete trailers that currently occupy the site.

Regulation of flows from Glen Canyon Dam:Martin has advocated for sometimescontroversial resource flows out of Glen Canyon Dam, high flows that mimic the river in its wilder, undammed days. The U.S. Geological Survey, in a press release issued last year, said experimental high flows in 2008 increased the area and volume of sandbars, expanded camping areas and boosted the number and size of backwater habitats where native fish rear their young. The flows are also credited with reducing non-native seedling germination, indirectly protecting archaeological sites from wind erosion, and cutting back the New Zealand mud snail population in Lees Ferry by about 80 percent while benefitting young rainbow trout.

“Insights gained about the effects of the 2008 experiment will be invaluable in helping determine the best frequency, timing, duration, and magnitude for future high flows to benefit resources in Glen Canyon National Recreational Area and Grand Canyon National Park,” said John Hamill, chief of the USGS Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center.

Colorado River Management Plan: The plan to allocate recreational river trips through the Grand Canyon was actually finalized in 2005, and park officials began implementing it in 2006, just before Martin took the helm. He’s overseen details for the plan – still controversial with some user groups – as they’ve continued to unfold.

Overflights: The issue of aircraft over Grand Canyon came to a head in the mid-1980s, after a mid-air collision between two aircraft killed 25. The National Parks Overflights Act of 1987 requires the Federal Aviation Administration and the National Park Service to work together to restore the natural quiet of Grand Canyon National Park through the development of overflight plans. Final rules were first proposed by the agencies in the mid-1990s, and have been hotly contested ever since, with pilots and air tour operators arguing for more freedom in the skies over the canyon, and many other park users – including boaters – begging for quiet. A new plan is due out any day (it was expected in December), and is projected to be just as controversial as past rules.

South Rim transportation plan: The park’s plan, issued in 2009, re-routed parking at Mather Point, one of the most crowded viewpoints on the South Rim. It also added stations at the main entrance, just north of Tusayan, to cut wait times. Enhancements to shuttle services have reduced overall traffic through Grand Canyon Village by up to 25 percent at peak times.

Martin says park visitors will notice significant improvements as soon as they approach the entrance station at the South Rim. “We had as much as two-hour waits at the entrance station, just chaos at Mather Point,” he said, referring to one of the most commonly visited viewpoints. “We moved the road, we fixed the entrance station so the longest waits are 10 or 15 minutes, created a beautiful walking esplanade all the way out to Mather Point. We replaced the shuttlebus fleet with green vehicles, and have linked that transportation system to Tusayan.”