“If you’re a retiree and want to learn something wonderful, come learn to paint,” advises Blanding, Utah, painter and art teacher Gary Guymon. He speaks slowly in a phone conversation from his home, but joy fills his voice.

A public-school mathematics and art teacher in California, Moab, and Blanding for 30 years, he followed his own advice in 1995 when he left the classroom for good.

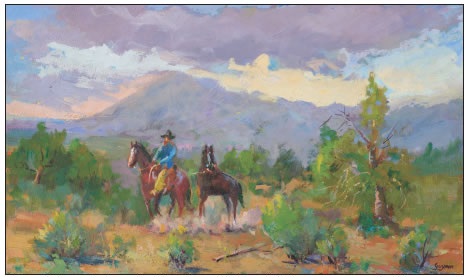

One of the paintings by Blanding, Utah artist Gary Guyman, that is currently on display at Edge of the Cedars State Park Museum.

Now through June, his oil paintings will hang at Edge of Cedars State Park Museum in Blanding. Most feature the landscape of southeastern Utah, which he describes as “one of the prettiest in the world.”

He paints on location en plein aire, an umbrella keeping him in the shade. If glare from the brilliant sun bounces off his palette or canvas, he can’t work. “Your eyes tend to restrict and you paint too dark.”

Drawn by the beauty of southeastern Utah’s seasons and skies, he works in all weather except downpours — oil and water don’t mix. When he returns home from painting, he cheerfully eliminates bugs and sand from his images by scraping upward with a palette knife to keep the grit from grinding deeper into the paint.

“Some people might call me kind of crazy. They see me off by the side of the road in all kinds of weather painting.” A tiny laugh wobbles his voice. “You’re out there in the wind. You tie things down and go for it. If it’s a wintry day, as long as the sun’s shining and you’re dressed for it, you can paint out in the snow on the mountain.”

If the weather’s really nasty, though, he will start a painting outside and return to his studio to finish it. At age 70, though he’s “still just a kid,” he finds bitter days harder to withstand than when he was younger.

Guymon chooses his subjects spontaneously as he drives along back roads, keeping away from tourist spots such as Rainbow Bridge, where people talk to him and interrupt his painting process. ”They tell you their grandma was an artist,” he chuckles.

As he meanders, something he can’t quite describe attracts him to a spot. “Maybe it’s . . . the color or the light or how things are coming together,” he muses. “I suppose that’s quite an individual thing.” He adds that he can find interesting compositions in his own or his neighbors’ yards.

He tries to finish a painting in 2 1/2 to three hours, relying on quick brush technique as the sun moves across the sky. If he can’t complete an image, he puts it aside and until the next day presents proper lighting conditions.

Brush strokes must become as spontaneous as fingering a flute or bowing a violin. “So you’re more into what you’re trying to get the subject to look like.”

An impressionist painter, he spent years learning his style. He begins a work by drawing no more than five basic shapes and filling them in with turpentine-thinned paint. That process allows him to determine which colors work together.

Next, he thickens the pigment to define lights, darks, and shadows. He fills in details to finish the painting. “That’s the big secret of making a painting work.”

He believes a strong relationship exists between art and mathematics. “In math you’re making comparisons. In art you’re doing the same kind of thing. You have to figure ratios.”

However, while math offers one right way to solve a problem, painting offers many acceptable solutions to a puzzle. Some answers just work better than others.

Besides landscapes, he paints historical subjects. He loves the history of southeastern Utah, particularly the period when the Utes, Navajos, and Mormons came together. “Those are interesting stories. I was lucky to know some of the folks who came into the area, and as a kid I used to talk to them.”

They told him that Four Corners was “kind of a blank map” in the 18th and early 19th centuries. American surveyors arrived in the 1870s, though records show that the Spanish wandered in as early as 1772.

In the early 20th Century, the LDS Church sent “a guy named Francis Hammond” from New York to develop southeastern Utah. Hammond selected the town site for Monticello, and recommended the land around White Mesa for ranching.

Guymon’s grandfather and grandmother helped settle Blanding. Guymon kept journals and made tapes of the tales he collected from them and other pioneers.

He admits that true impressionist paintings don’t tell stories. But he can use some impressionistic techniques in historical paintings by incorporating people’s interactions, as well as old barns, grazing horses, and a cowboy or two into his landscapes.

His show at the Edge of Cedars contains 45 paintings and hangs through June 30. “People have enjoyed coming to see it,” he says.

During April and May, he’ll teach oilpainting techniques to four or five people at a time so he can accommodate different skill levels. People interested in taking a class should call the Edge of Cedars State Park Museum.

He believes schools should include art classes, and loves teaching kids. “If we’re going to have children that are going to make great contributions, we need to allow them to have creative experiences.”