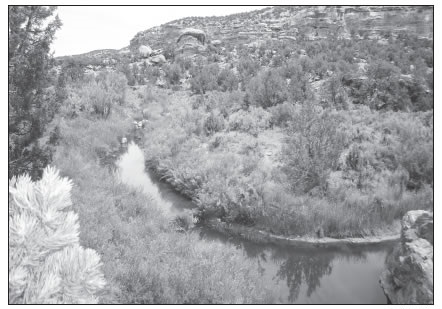

Recapture Canyon in Southeast Utah is a placid place in late July. Today, under a soft cloud cover that prevents the heat from becoming brutal, the only things moving are four hikers, birds flitting through the brush, and the ever-present flies and gnats.

A trail, part of a longer network that goes along the canyon rim, winds from one end of the canyon near the Recapture Dam, which sits just off Highway 191 between Monticello and Blanding, to the rim five or six miles to the south.

The BLM’s Monticello (Utah) Field Office is doing an environmental assessment of a proposal to allow motorized recreation on a trail through scenic Recapture Canyon near Blanding. The trail was built without authorization in 2005. The canyon includes riparian areas and numerous archaeological sites. Photo by Gail Binkly

The scenic route follows the meanderings of Recapture Creek through a more riparian environment than the typical landscape of Southeast Utah. There are willows, cottonwoods, even beaver ponds.

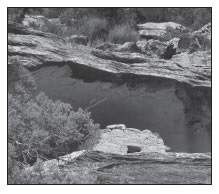

But what makes the trail spectacular is its archaeology. The canyon harbors numerous Ancestral Puebloan sites ranging from cliff dwellings in high alcoves to room blocks, scattered potsherds and middens nearer the creek.

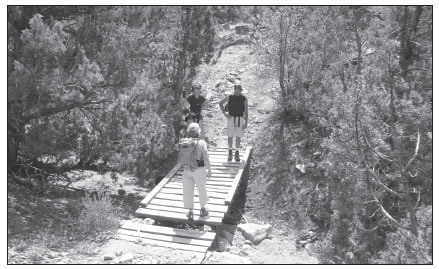

Late in 2005, someone constructed an off-highway-vehicle route through the canyon. These people — it likely took more than one individual — shored up curves, installed culverts, even built a wooden bridge over a creek crossing.

The result was a series of trails drivable by all-terrain vehicles and dirt bikes. Problem is, the route, which lies on BLM lands, was not authorized.

Today it is closed to motorized use while the BLM decides what should become of it. Meanwhile, an investigation into the culprits who built it is ongoing.

The case is a classic example of the intense struggle taking place between motorized and non-motorized users on public lands across the West and particularly in the Southwest, where ancient cultural sites are an added factor to be considered in deciding what uses are appropriate in which places.

Illegal acts

The illegal trail network crosses at least nine archaeological sites bigger than an acre each, according to material from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and its construction damaged at least a dozen sites.

Yet it wasn’t until September 2007 that the trail was closed to motorized use, and a proposal to grant San Juan County a rightof- way for the system of trails is still under consideration by the BLM.

None of this sits well with Ronni Egan, executive director of the Durango, Colo.- based Great Old Broads for Wilderness, an environmental group that monitors and documents damage to public lands.

“How can you consider issuing a rightof- way for the trail when there are still two criminal investigations going on related to it?” she asked as she led this reporter and two Blanding residents along the trail.

The first investigation, into the trail’s construction, won’t continue much longer, as the statute of limitations for the offense will run out late this fall, according to Tom Heinlein, manager of the BLM’s Monticello Field Office.

Heinlein declined to say whether charges are forthcoming. However, he said the construction of the trail was definitely illegal, although at the time the area in question was designated as open to crosscountry motorized travel.

“The actual surface disturbance was unauthorized and illegal,” he said. “It involved destruction of public property. There are also violations of cultural resource laws.”

Felony charges can be filed for damage to archaeological sites that exceeds $500 and was done knowingly.

The second investigation involves looting that took place in mid-2007 at a large archaeological site accessible from the illegal trail. Known as the Recapture Great House, the site includes a multi-story pueblo from the Pueblo II period of the Ancestral Puebloans, according to the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Egan said she spoke to a former BLM employee who saw the damage. “ATV tracks were all over, and pot-hunting holes had been dug,” Egan said. “The looters had even left their tools.” The BLM subsequently issued an emergency closure for 1,871 acres in the Recapture Canyon area in September 2007.

Environmental groups have charged that the BLM dragged its heels in responding to the illegal trail, both by leaving it open too long and by initially conducting a cursory investigation. Egan said the BLM officials first said the trail had not been mechanically constructed, then — after being presented with evidence such as the wooden bridge — did only a brief investigation and closed it. Heinlein, who was not the field manager at the time and came to his position in 2008, said as far as he can tell, the investigation was never closed.

“Several people have told me adamantly that it was, but I have no evidence in my office that it was,” he said. However, he said it was put on the back burner because of a mammoth investigation into the excavating and selling of stolen cultural artifacts that resulted in the arrests of 24 people in 2009.

“The [Recapture] investigation was delayed, and it continues,” he said.

Mitigating the damage

Heinlein said the BLM is preparing an environmental assessment of the county’s proposal for a right-of-way for the trail. Three other alternatives are being considered as well. “The county’s is the most extensive alternative,” he said. Two options would open smaller portions of the trail to motorized use, and the last, the no-action alternative, would maintain the emergency closure, meaning motorized use would not be allowed.

Even if the BLM chooses to let motorized use resume on all or part of the trail, that cannot happen until the damage already done has been mitigated, Heinlein said.

The emergency-closure order states, “The emergency closure area shall remain closed to OHV use until the considerable adverse effects leading to the closure have been eliminated and measures have been implemented to prevent recurrence.”

“That’s a very high standard to meet,” Heinlein said. “Basically that means, regardless of the alternative we ultimately accept in the EA, we cannot lift the closure till the adverse effects have been eliminated. We could not implement the decision till the damage has been eliminated.”

That would entail stabilizing or covering sites that have been eroding or have been opened, relocating trails around sites, and similar measures, he said.

The Monticello Field Office approved a revised resource management plan in 2008 in which the Recapture area is classified as allowing motorized travel on designated routes only, Heinlein said. The Recapture Trail itself was not designated in that plan, but it will be if the BLM chooses one of the alternatives to grant the right-of-way.

Heinlein said re-routing the existing trail to avoid cultural sites would be difficult. “It’s a tough one given the resources that exist and the fact that the trail was already roughed in,” he said. “Even if we chose an alternative that had re-routes, there are not a lot of alternative places to go.”

The people who created the trail “did not put it in the most advantageous places, both in terms of cultural resources and trail maintenance,” he said. “They didn’t really understand grades and switchbacks and erosion and things.”

However, he said, the builders certainly did a great deal of work. “A lot of time was spent on that trail,” Heinlein said. “I would like to be able to harness that energy for other purposes.”

Access for all

Many of the studies necessary for the EA, such as wildlife surveys, have been completed, but a cultural-resource study known as a Section 106 process (after the relevant section of the National Historic Preservation Act) is far from finished. In this case, the process involves monthly meetings with interested stakeholders to decide the best way to protect and preserve the archaeological sites that would be affected by the trail. “The most complex part of the EA process by far is the cultural part,” Heinlein said.

The unknown persons who built an OHV trail through Recapture Canyon even constructed this wooden bridge over the stream. Photo by Gail Binkly

The lengthy process is frustrating to San Juan County officials, including Commissioner Lynn Stevens, one of the county’s leading advocates of motorized use. He said when the trail was first closed, the state director of the BLM indicated it would be only through that winter while a mitigation plan was worked on. “That was three years ago, and we’re probably a year or more away from even getting an agreement in the 106 process.”

Stevens believes motorized users, particularly in his county, are being unfairly painted as renegades and villains. “It’s an unfair label to say San Juan County is hostile to the environment,” he said.

“The motorized-recreation people in San Juan County are probably every bit as environmentally conscious and interested in preserving the values as any other population.”

He believes motorized trails are important for “people that are a little older or less ambulatory, or younger ones who want to see more in less time.”

“We spend millions of dollars to accommodate Americans with disabilities so they won’t have difficulty moving around our cities, yet that seems to be totally inapplicable to some of our recreational areas.”

Stevens maintains the trail was not built illegally because the BLM management plan in effect at the time listed the area as open to cross-country motorized travel. “There aren’t restrictions on how you can hike or bike in the open area,” he said. “The allegation that it was done illegally has yet to be substantiated.”

He said portions of the Recapture Trail has been informally in use for many years, and much of it came about simply through repeated use, though some mechanical work was clearly done. “There were some tree stumps and limbs removed, some rocks moved,” Stevens said. “There is one crossing of a stream where a wooden bridge was constructed, which probably saves the environment rather than harms it.”

But however it came about, county officials strongly believe the trail should be reopened to OHVs.

“Recapture Trail is very important to the people of Blanding,” Stevens said. “First, it’s a great exposure to the archaeology of the entire county, a great recreational and educational experience.

“Also, you can leave your house anywhere in Blanding and be at the trailhead in 15 minutes or less. Even with a very slow-moving vehicle, stopping and pointing out the archaeology and other beauties of the canyon, you can be back off the trail in an hour and a half.”

But Egan says not all motorized users are driving the trail gently and eying their surroundings. She says parts of the illegal route have clearly been banked for speed and were driven that way when it was open. “As vehicles go around the hills fast they throw up dirt on the uphill side of their tires, and they make deep tracks,” she said. “You know how a race course is banked on the turns? The trail is banked like that.”

Sacred potsherds

Partly because of the county’s strong advocacy for motorized use, allegations linger that county officials were complicit in creating the road. Stevens said those are false. “There have been allegations that the county road department got involved with county equipment or county people. There’s no record of that, and our road department keeps very meticulous records.”

According to Stevens, the county did make two stiles (locals call them cattle-guards) that are used in the Recapture network to allow ATVs to climb a fence without going through a gate, but those are on the rim. “The county did construct several of those. They’re made in three pieces,” he said. “To my knowledge there’s only two cattle-guards made by the county on part of the trail and it’s the part of the trail that’s still open. So the claim that the county went in and constructed part of the trail illegally is false.”

Stevens, like many other locals, sometimes grows impatient with the idea that every archaeological site and artifact needs to be protected.

“I’ve been through most of these 106 sessions where the arguments are so ethereal — so ridiculously speculative on what damage could be done to a site 150 feet up a cliff, 200 yards from a road — that it just becomes annoying.

“Almost every potsherd that gets run over, you’re violating something sacred, yet there are more than 30,000 archaeological sites known in San Juan County, Utah. They can’t all be significant.”

But he does not condone the sort of willful looting that was alleged in the 2009 artifacts cases, the vast majority of which involved people from San Juan County. “San Juan County and the sheriff have gone on record vocally that looting of sites is illegal and we don’t support that at all.”

But the proximity of a road to cultural sites is not reason enough to close the route to ATVs and dirt bikes, Stevens believes. He said there are very few places where motorized use is not appropriate.

“There may be areas where it’s inappropriate from a safety point of view, but from an environmental-damage point of view, that has to be looked at pretty closely.”

Advocating education

Bob Turri of Monticello likewise believes in widespread access for motor vehicles on public lands. Turri is a member of the board of SPEAR (for San Juan Public Entry and Access Rights), a San Juan County-based off-road advocacy group. He echoes Stevens’ concern about access. “We have so many people in our organization that are old, and some handicapped. They were accustomed to going out and enjoying this wonderful land here and they can’t do it any more but they found by using ATVs or Jeeps that they are able to continue doing that.”

Like Stevens, he said the Recapture Trail is important because of the opportunity to view Ancestral Puebloan ruins.

“I strongly believe the archaeology belongs to the people, not archaeologists or agencies, and they have a right to view it.”

SPEAR is often fingered as a suspect in the construction of the Recapture Trail, but Turri said neither the organization nor the county had anything to do with it. He said he does have an idea who built the trail, but they were “two common guys” acting without SPEAR’s approval. He isn’t sure whether they knew they were violating the law.

“We do advocate responsible use, although I believe every user group has its renegades — people you can’t control,” Turri said.

“I know the trail was built illegally. There’s no question about that.

“They did a lot of work and some of it was nice, but it’s really unfortunate that happened because it really set us all back. I would certainly have developed the trail differently in certain places. We’re not interested in damaging those sites.”

Turri said a BLM law-enforcement agent investigating the incident asked him what he thought should happen to the people who built it. “I said, ‘Those people are not criminals, they’re some guys that made a real mistake.’

“A fine and probation — that sounds reasonable to me. You can’t let them go unpunished, I understand that, but I hope they aren’t too harsh on them.”

But Turri believes whoever looted the Recapture Great House deserves sterner penalties. “Archaeological vandalism is a different story. Those people deserve some pretty harsh treatment.”

He said a distinction must be made between responsible ATV riders and rogues. “We’re not all bad people because we ride an ATV, but the response I get is, ‘You’re exactly the same, you want to tear up the land’.”

Hikers and cyclists do damage, too, he said, and he witnessed that during his 25- year career with the BLM. “The Sierra Club came in once and did a hike in Grand Gulch and we had to hire a crew to clean up the trash they left. All user groups have a rebel or two.”

However, Turri conceded there seem to be more “rebels” in the ranks of motorized users than hikers, a fact that pains him.

He was with some other riders in the La Sal Mountains once, putting up signs marking numbered ATV trails, when they encountered four men on ATVs who accused them of putting up closure signs. “They were the true rebels. They were all carrying guns and drinking too. They said, ‘We’re going to follow behind you and shoot down your signs, and we have plenty of ammo’.”

Such renegades cast a pall on the image of all riders, he said. “It’s embarrassing to me if I see that somebody has misused a trail or been off the trail.”

But Turri believes that in the seven or eight years he has been active in SPEAR, he has seen a change in attitude. “The same guy that said, ‘Nobody is going to tell me where to ride!’ now is saying, ‘Stay on the trail.’ So education is really the answer, but it’s slow.”

‘A special place’

But Egan and other environmentalists maintain that some places just aren’t suited to motorized travel, and Recapture is one of them. Asked if re-routing would solve the problems with the trail, Egan said, “We believe that motorized use invites vandalism.”

The Ancestral Puebloan ruins in Recapture Canyon include many cliff dwellings. Photo by Gail Binkly

Stevens said the county is willing to consider modifications to the existing route. He has traveled the trail numerous times, and agrees there are at least two places where it goes over a site — one a “cyst box,” or storage hole, the other a potential burial site. “I’ve told the BLM and the 106 parties that [having motorized use on] the entire 19 miles of the trail is not mandatory. They can rule some of it is inappropriate and if they have scientific facts to back it up, the county won’t argue, but they need to have something more than emotion.”

But Egan believes permitting OHV use on the trail after motorized users created it through a criminal act is “like giving the keys to the safe to the burglars and saying, ‘Help yourselves’.”

She wants to see the route dedicated to hikers, cyclists, horseback riders. “It could be a great asset to Monticello and Blanding.”

In the silence of the canyon this July morning, bird songs can be heard clearly. A fellow hiker, Mary Costello of Blanding, identifies them: scrub jays, rock wrens, chats. High in the red-rock cliffs, Ancestral Puebloan dwelling sites seem to look down on the trail. There is a sense of peace that belies the controversy that swirls over these few miles of desert.

“We think this is a special place,” Egan says.

That seems to be one of the few things people can agree on.