Native American tribes in the Four Corners region are gearing up for a battle over plans to haul uranium across their lands to the White Mesa Mill near Blanding, Utah.

White Mesa is the only fully-licensed, conventional uranium mill in the United States. It is also the only mill capable of processing vanadium, a mineral used in steel production and large-scale battery storage for community solar, wind and geo-thermal energy projects.

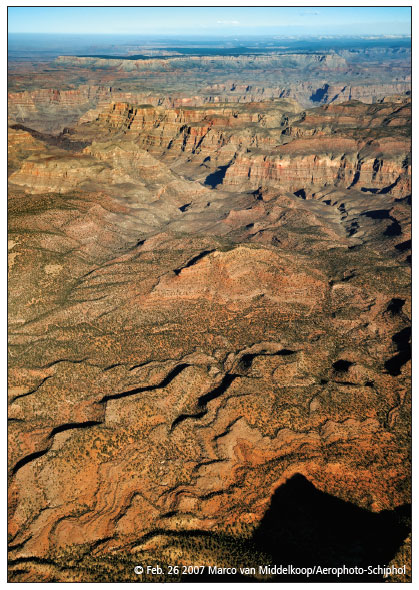

An aerial view over the Grand Canyon from the southwest above Hualapai and Havasupai reservations.

The mill, owned by Energy Fuels Resources, Inc., a Canadian company, accepts uranium ore and alternative uranium feed sources and is permitted to store uranium wastes in containment cells at the site.

According to the company’s website, of the seven uranium mines in the Four Corners states, two are near the Grand Canyon, and two near the newly designated Bear Ears National Monument.

The Canyon Mine, six miles from the Grand Canyon, is within Havasupai reservation land in Arizona in the Kaibab National Forest. Originally owned by Energy Fuels Nuclear, the mine was purchased by Denison Mines in 1997 and by Energy Fuels Resources Inc., in 2012.

After a series of public hearings in 2016, the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality issued an air-quality permit to Energy Fuels Resources to operate Canyon Mine near Red Butte, a mountain held sacred by the Havasupai Nation. According to documentary film producer and Indigenous Media founder Klee Benally, the Red Butte- Canyon Mine location was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places as a traditional cultural property in 2009. At the hearings, ADEQ affirmed that Arizona state law does not allow the department to include non-air quality requirements in the processing of these permits.

No laws currently ensure protection for sacred sites on federally held lands, said Benally.

According to information released in a statement by the Grand Canyon Trust, a 2010 U.S. Geological Survey report noted that past samples of groundwater beneath the mine exhibited dissolved uranium concentrations in excess of EPA drinking-water standards. Groundwater threatened by the mine feeds municipal wells, seeps and springs in Grand Canyon, including Havasu Springs and Havasu Creek.

Aquifer protection permits issued for the mine by Arizona Department of Environmental Quality do not require monitoring of deep aquifers and do not include remediation plans or bonding to correct deep aquifer contamination.

According to HaulNo!.org, the website for a group organizing an awareness campaign about the route, the public expressed additional concerns about the proposed route Energy Fuels may use to haul radioactive ore 300 miles to the White Mesa Mill. The trucks are to be covered in tarps. ADEQ responded by making the requirements more stringent, requiring the tarps to lap over the edge of the truck beds by 6 inches, secured every 4 feet with a tie-down rope.

But critics say the uranium poses a serious threat to the watershed and the people on the haul route. “It should stay in the ground,” testified Benally at the August ADEQ hearing, “or you’re going to have a serious battle.”

Examining alternatives

Arizona State Route 64 provides the eastern access to the Grand Canyon, and the most direct egress to White Mesa Mill in Utah from Canyon Mine. The road is winding and crowded with slow-moving, heavy tourist traffic.

However, up at park headquarters the highway turns south toward Tusayan, through Havasupai tribal land. Although the southern access – Route 64 connecting to U.S.180 and I-40 – will add mileage to the haul, it is a less congested route, taking the ore through Flagstaff. There the trucks turn north on Highway 89 to access a nearly nonstop course through the Navajo Nation beginning at Gray Mountain, the edge of the reservation.

Haul No! is planning an “action tour” along the proposed route, where 25 trucks could be hauling up to 30 tons of ore per day when the mine is fully operating. The production of high-grade uranium ore could be as high as 109,500 tons annually.

Energy Fuels is permitted to stockpile up to 13,100 tons of uranium ore at Canyon Mine.

Curtis Moore, marketing vice presi dent for Energy Fuels, told the Free Press that the company is still looking at alternate haul routes. “We’re still considering our options. We’re looking at a few different routes, and times of day, like night schedules to avoid tourism. The mine may or may not be in production in the future.”

But the route on the map today, shown on the Indigenous Actions website, crosses through a dozen Navajo Nation chapters including Cameron, Tuba City, Kayenta, near Monument Valley, Red Mesa and Montezuma Creek, where it turns north through Ute Mountain Ute tribal land at White Mesa, the native community three miles south of the mine.

Unhappy history

Today, more than a thousand abandoned uranium mines and surface sites still await remediation from extraction during the Cold War. Health problems from exposure to soil and water contamination continue to plague the Navajo people. Many of those sites are on the current haul route.

In 2005, the Navajo Nation Council passed the Diné Natural Resources Protection Act, prohibiting uranium-mining and processing on any Navajo sites or land.

A reinforcement measure, the Radioactive Materials Transportation Act of 2012, prohibits the transport of equipment, vehicles, persons or materials for the purposes of exploring, mining, producing, processing or milling any uranium ore, yellowcake, radioactive waste or other radioactive products across the Navajo reservation.

The act gives the nation the right to regulate transportation of uranium materials, charge a fee, restrict routes and time of day for transport, or completely disallow it.

In 2013, Eric Jantz, staff attorney at the non-profit New Mexico Law Center in Santa Fe, told the Free Press then that the fundamental definition of “sovereign nation” gives tribes the right to exclude people from their land.

At that time, Wate Mining was faced with a similar uranium-transportation challenge in Arizona. The mine site was located on a parcel of state land in Big Boquilllas Ranch sandwiched between the Hualapai and Havasupai reservations and surrounded by Navajo Nation checkerboard fee land. There was no access to transport options from any direction without permission from the Navajo government. The mining company applied to the Navajo Nation Department of Justice asking to transport the ore out of the site to the Blanding Mill. The request was denied.

Resolutions of Opposition

In December, the Oljeto Chapter, in Monument Valley, unanimously passed a resolution asking the Navajo administration and council to ban the transportation of the ore through the Diné communities. A week later, a similar resolution was passed at the quarterly meeting of the Western Navajo Agency Council, the group of chapters directly impacted by the haul route.

“Oljeto and the surrounding communities have been plagued by decades of toxic uranium-mining activities, causing serious health problems for Diné miners and families,” wrote James Adakai, president of Oljeto Chapter, sponsor of the agency resolution. “We support Havasupai tribal council opposing the mining permits because it will desecrate their sacred lands and damage their water supply. Now it goes to the capital of the Navajo Nation for final approval.”

Martin explained that he is “not sure” concerns about the sovereign right to ban transportation over reservation land are accurate, that “state and federal” regulations possibly supersede tribal regulations.

But Walter Phelps, Cameron Chapter council delegate, told the Free Press that the resolutions will come before the Navajo Resources and Development Committee first. “We are able to enforce it through the Navajo Department of Transportation,” he said, and the NDOT rangers will police the highways in order to protect public safety.

Changing state transportation laws takes time, explained Roger Clark of the Grand Canyon Trust. “If the Navajo legislation plays out, it will be interesting to follow. Hopefully there will be an opportunity to debate [the interstate commerce laws] and stop the haul route.”

Energy Fuels remains somewhat vague about the hauling details. “They hold all the cards,” Clark told the Free Press, “but that doesn’t mean the affected people should sit on their hands and wait.”