Ember Moreno of Mesa, Ariz., grew up in Blue Canyon, near the Tuba City/Red Lake area of northern Arizona.

She remembers, as a child, “going to get water from a water pump at the covered uranium site right there east of Tuba City,” a site now known as Site 160, where toxic wastes were dumped. “We drank the water, we washed our clothes at the spigot near the side of the road in front of where the trailers are now.

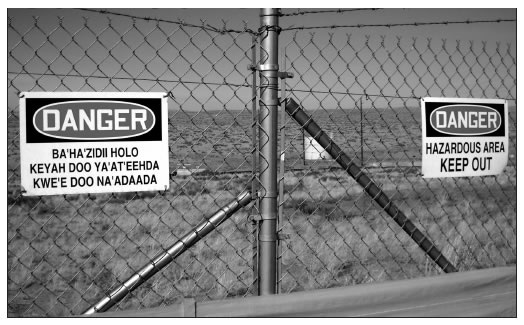

Site 160, where hazardous materials were deposited, sits on the north side of Highway 160 four miles east of Tuba City, Ariz., across the road from the site of the former Rare Metals Mill, which processed uranium ore from 1956 to 1966. Photo by Sonja Horoshko

“I was born in ’57, so this was in the early ’60s.”

She said there were always several vehicles lined up and everyone was getting water there.

“Nobody ever said, ‘Don’t drink it!’” recalled Moreno, now an insurance verification representative at the Banner Heart Hospital in Mesa.

Contaminated water

Fifty years later, the legacy of uranium- mining still hangs like a specter over the Navajo Nation.

Tourist maps call the country in the Western Agency of the Navajo Nation, the area near the Grand Canyon, a painted desert. Mineral-rich land in the yellows, salmons and reds of earth and sandstone unfolds under a cerulean sky north of Flagstaff, west of Kayenta and south of the Glen Canyon Dam.

The region spreads on both side of highways 89 and 160, dog-legging the Hopi-reservation mesas high above the Little Colorado River and other small drainages that meander past hamlets such as Black Falls, Gap-bythe Way, Coalmine, Cameron, Gray Mountain, Inscription House, Grand Falls, Black Mesa, Oljeto and Kayenta.

An Indian Country map circa 1960 hangs in a Kayenta café identifying these places with symbols. Four miles east of Tuba City, a black dot marks, “Rare Metals,” as if it were a town.

Instead, it is the site of Rare Metals Corporation, a uranium mill that processed yellow ore dug from hundreds of mines picked out of the desert to fuel atomic-energy projects during the Cold War.

From June 1956 to November 1966, the Tuba City Rare Metals Mill processed 796,489 tons of uranium ore. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, when the mill closed and control of the site reverted to the Navajo Nation, three connected milltailings piles containing some 800,000 tons of material and three evaporation ponds remained. The mill became a Superfund site.

All that is left of the Rare Metals Mill today is a fenced remediation site, some concrete building foundations overgrown with weeds near the highway, a few scattered mobile homes, used until recently as residences — and concern that the groundwater downhill from the mill contains elevated concentrations of contaminants related to milling operations.

In 1968, according to the U.S. EPA, the surface of the tailings piles was treated with a chemical binder to keep the material intact, but by 1974, the crust “was no longer effective.”

In 1972, a gamma-radiation survey of the Tuba City mill site and adjacent area found “anomalous gamma radioactivity” at 14 sites, seven of which contained uranium tailings. “The contamination was attributed to dispersal of tailings material by wind action,” states the EPA’s web site.

In June 1988 the DOE, assuming responsibility for remediation of the Rare Metals site, began construction of a disposal cell. When completed in 1990, it covered about 50 acres. Nearly 2.3 million tons of contaminated materials are entombed in the cell and, according to the DOE fact sheet, the cell contains “all of the residual radioactive materials at the mill site, the contaminated windblown materials from surrounding properties, and debris from the demolished buildings.”

Although the DOE has long-term responsibility for the site, the Navajo Nation retains title to the land.

A plume on the move?

But the hazardous materials in the area continue to defy containment. The DOE subsequently found a contaminated groundwater plume covering about 320 acres extending downhill to the the south and southwest from the former mill site.

Levels of molybdenum, nitrate, selenium, and uranium in the 3.8 millioncubic- yard contaminated groundwater plume exceed the U.S. EPA’s maximum safe limit.

The DOE’s groundwater-remediation strategy is designed to reduce concentrations of these five contaminants in the groundwater plume, which extends from the former mill site toward the Tuba City Open Dump site and beyond it to the Moenkopi Wash drainage. However, the precise source of the contamination is unclear.

Complicating the situation is the presence of the dump, which straddles the Navajo-Hopi border and operated from 1950 through 1997 with limited oversight by the BIA. During that time it was an uncontrolled dump that received solid waste from local communities in the Tuba City and Moenkopi areas. There are allegations that hazardous wastes from the mill were also buried there.

In 1995, the BIA began studies of soil and groundwater in the vicinity of the mill and dump. Those studies resulted in the shutdown of the dump in 1997. From 1999 to 2008, the BIA funded studies by the Hopi tribe to investigate the shallow groundwater near the open dump site; those studies found contaminants in excess of EPA standards.

Further studies at the dump site have concluded that most of the material in the dump is municipal solid waste. Although the assessments found arsenic, strontium, vanadium and copper at elevated concentrations compared to native soil and rock, they found that the contaminants were not due to hazardous waste present at the site.

The BIA continued doing groundwater monitoring, installing 38 monitoring wells. The results showed elevated levels of 13 chemicals in the shallow groundwater near the dump site. Uranium was one of them; it was detected immediately down-gradient of the site at up to eight times the EPA Maximum Contaminant Level, MCL, for drinking water. Outside the site, contaminant concentrations in wells ranged from non-detectable to 2 times the MCL. By 2007 the BIA had begun investigating possible additional sources of contamination. The agency collected testimony from multiple residents who said that Rare Metals Mill wastes and tailings were deposited at the dump.

Carl Warren, project manager for EPA’s Region 9, told the Free Press that the EPA has no record of this testimony, although there may be a record with the BIA. BIA officials did not return phone calls by press time.

“Even though actual EPA records do not exist of this testimony,” Warren said, “there are enough alleged reports that waste material may have been brought there from the former milling plant. Actual records do not exist at the open dump site because it was uncontrolled, unsecured and unmanned. However, there are reports that debris was brought there. We’re taking these reports seriously and will conduct more formal investigations into the stories.”

Marbles and bolts

Residents also tell of peoples cavenging for construction material from condemned buildings in the area around Rare Metals Mill and the open dump. Whole families would go to take apart the houses near Rare Metals before they were demolished, using materials found to repair existing homes.

The scavenging was a result of the Bennett Freeze, a moratorium on development in a 1.5-million-acre area imposed in 1966 by Commissioner of Indian Affairs Robert Bennett because of land disputes between the Navajos and Hopis in the Western Agency area.

“For more than 40 years, Navajo families residing in the Bennett Freeze area lived under an oppressive and unjust law that has essentially made poverty mandatory,” Roman Bitsuie, executive director of the Navajo-Hopi Land Commission Office, told reporter Kathy Helms of the Gallup Independent in March 2009.

Residents of the Bennett Freeze area were barred from making any improvements — even minor repairs to their homes and property, such as fixing a leaky roof. It was against federal regulations to do new construction or develop new businesses.

Thus, in desperate visits to the dump and mill site, people removed what they could use to save homes and buildings.

Children brought toys and odd items from the dump, while adults prized nuts and bolts, metal scraps and construction materials. People recall friends and family moving into abandoned houses and trailers near the Rare Metals Mill; some even moved the temporary homes off the site onto personal property.

The U.S. EPA agreed to work with the tribes and BIA to evaluate permanent closure options for the dump. Today, partners involved in the complex dump-remediation project include the Navajo Nation EPA; U.S. EPA; Hopi Water Resources Department; BIA; DOE and Indian Health Services, which is responsible for the permanent fence erected recently around the Tuba City Open Dump site.

Three years ago, the U.S. EPA bored an additional 250 monitoring wells, identifying MW-07 at the dump site as showing the highest concentration of uranium in the shallow groundwater.

At community meetings in Tuba City and in Moenkopi last October, EPA officials explained the Open Dump field work on MW-07. The project was completed this February. It included surface assessment, soil borings and pits, tests of soil and waste samples to determine chemical and radiological content, excavation of waste that may contribute to elevated uranium concentrates in the shallow groundwater, disposal of all hazardous wastes during excavation, installation of two shallow groundwater wells and restoration of the disturbed area.

Results of the investigation and the feasibility study evaluating long-term clean-up and closure options are expected to be done by mid-March.

A new site

The relationship between the Rare Metals Mill and the Tuba City Open Dump sites has been studied for more than 10 years. Remediation is taking place.

But, like radioactivity itself, the problems associated with the uranium mill seem to linger.

Several years ago, rumors surfaced of another waste site across Highway 160 from the former mill. Residents reported seeing trucks carrying 55-gallon drums of waste and burying them there. The Highway 160 Site is about four miles northeast and possibly upgradient of the dump.

It is listed in EPA updates as a potential source for the radioactive materials found in the groundwater at the dump.

Warren concurs, noting that Site 160 was “found about seven years ago. . . the Navajo Nation has received funding from the DOE to address the clean-up.”

In a Feb. 11, 2010, press release, Cassandra Bloedel, environmental-program supervisor with Navajo Nation EPA, stated, “In 2003, information was received by local families who knew of the contaminated site. They were witnesses to those uranium activities in the late 1950s and in the early 1960s. In February 2004, the site was reported to the USEPA, Emergency Response… investigation that followed in May that year showing radioactive waste located within the 7.6 acre site.”

According to the press release, the NNEPA hired a contractor in January 2006 to investigate. He “identified further mill-related waste, found the mill balls used in uranium processing, and showed the site had high areas of radioactivity,” added Bloedel.

Whose responsibility?

In July 1962, the Rare Metals Corp. merged into the El Paso Natural Gas Company. EPNG signed a new contract with the Atomic Energy Commission, which later was incorporated into the DOE.

Bloedel stated in the press release, “The company did their own investigation of the site and determined that Site 160 did possess waste from the Rare Metals Mill. The DOE then fenced in the site to protect humans and livestock, and a palliative cover that hardens like a crust was placed on top to prevent contamination leaving the site due to typical winds recorded as high as 50 miles per hour.”

The Omnibus Appropriations Bill passed in March 2009 provides $5 million for cleaning up Site 160.

On Feb. 11, the Resources Committee of the Navajo Nation Council passed legislation that also provides $4.5 million to clean the site.

“Responsibility at this site is a challenging question,” said the EPA’s Warren. “We may need forensic analysis to determine responsibility. With that, the EPA will evaluate all available information, ascertain responsibility and compel the responsible party to participate in the clean-up.”

Meanwhile, the people who lived in contaminated homes, drank contaminated water and breathed contaminated air are left to deal with the longterm consequences to their health.

“The DOE created a demand for uranium to feed the U.S. Cold War strategy,” said Ed Singer, president of the Cameron Chapter, one of the Navajo Nation’s Western Agency chapters.

“The Navajo people are to this very day paying for that with their health and lives. Large areas of Navajo land and scarce waters upon it as well as the lives and health of the Navajo people became the biggest sacrifice cost ever visited on a people.”