From 1862 to 1868, more than 8,000 Navajo women, children, babies, warriors, cooks, blacksmiths, herders, farmers, teachers, weavers, warriors, mothers, fathers, elders, chiefs and medicine men were forced out over the thresholds of their hogans and herded to an Army reserve at Ft. Sumner and the Bosque Redondo, in New Mexico.

Many walked 22 days to the destination they call in Navajo Hwéeldi (The Fort), 400 miles away. An estimated 2,500 people died from exhaustion, hunger, illness, disease and exposure on the walk, drowned in the Rio Grande and Pecos rivers on the way, or died while incarcerated at Hwéeldi.

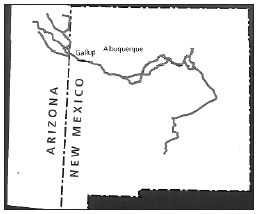

The routes proposed for a Long Walk National Historic Trail wind from Canyon de Chelly, Ariz., to Bosque Redondo, N.M. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service

Orders to remove the small, nomadic Mescalero Apache tribe preceded the campaign against the Navajos. By the time success was assured just over 500 men, women and children — the whole tribe—had surrendered to banishment at Bosque Redondo.

The event is a black mark on the U.S. government, bruising even more deeply because of the self-imposed Navajo and Mescalero Apache silence about the walk, and U.S. government denial and revisionist storytelling around the four-year incarceration.

Some historians place the Long Walk under the umbrella of Manifest Destiny, “implying that Navajos deserved the violence and brutality visited upon them,” said Jennifer Nez Denetdale, associate professor of history at Northern Arizona Univ ersity, and author of “Reclaiming Diné History: The Legacies of Navajo Chief Manuelito and Juanita.” “Forced removal of the Diné was part of the cycle of invasion, conquest, removal and colonization that facilitated white settlement of America.”

But today, especially in the Southwest, the hush around the topic is ending. Many current projects are broaching the tragic event.

The most public is the National Park Service’s proposal to create a Long Walk National Historic Trail. A feasibility study / environmental impact statement has been released that proposes four alternatives regarding a trail that could stretch as far as 1,350 miles along routes recognizing the forced removal of the Mescalero Apache and Navajo people.

Harry Myers, retired project leader for the NPS National Trail System, was the lead planner when the project was launched in 2002. Then-U.S. Rep. Tom Udall of New Mexico introduced legislation in Congress to establish the Long Walk Trail feasibility study.

Myers told the Free Press that Udall had a real commitment, “a belief in the need for this project that really showed.” When he received the order to proceed, Myers said, he brought in Robert Begay, now director of the Navajo Nation Archaeology Depart ment, and Holly Houghten, tribal historic preservation officer for the Mescalero Apaches. Together they developed a plan that would enable the Park Service to work with the tribes to do what all agreed was essential: Do justice to the story.

Begay said the Park Service “did a pretty good job of listening when we made suggestions that they needed public input from the five Navajo regions. They hired the interpreters and held the ethnographic intake meetings, which we facilitated for our people. When we wanted them to present a resolution in support of the trail designation before the Navajo Nation Council they did an excellent job.”

But despite positive public comment before the council in 2006, the resolution to support the trail lost by 10 votes.

“It’s a very, very sensitive issue, especially among the elders,” Begay said. “Basically it’s viewed as a bad, really awful part of Navajo history that must not be spoken of.”

Intake meetings in the Navajo and Apache communities showed the divisiveness of the issue. Myers said the Park Service laid out the essential purposes of a historic trail — how it is not for recreation but for interpretation and education. “But people were really commenting on whether it should be talked about at all. We heard that they were not supposed to talk about it. ‘It’s, yii yah, scary! Something bad will come back and hurt us,’ they said.”

At the same meetings, though, many young people said they wanted to talk about the Long Walk because their collective heritage will be lost if they don’t.

“I went to the meetings,” said NAU’s Denetdale. “Out of that came the motivation to write my books. It was so powerful, some people waited all day to tell their story. Navajos are very forthcoming about the dehumanization that took place. They were treated lower than animals by the American people.”

She said the Navajo oral tradition accurately “bears witness to the U.S. government’s unwillingness to recognize its responsibility to Navajos and other Native people.”

“The Mescalero Apache people did not talk about it and now they have very little memory of it,” added Myers. “Loss and lack of knowledge about the Long Walk experience is still going on today.”

The silence on the subject spreads across the borders around the tribes. What young Navajos and Mescalero Apaches do not know, most people of the dominant cultures surrounding the reserves also do not know.

Irene Nakai Hamilton teaches language arts in Kirtland Central High School, N.M. This summer she attended, “The Middle Ground: Government Reports Documenting U.S. Relations with the Navajo Nation,” a seminar at the University of Northern Colorado. “Last year the participants studied the Long Walk and went to Bosque Redondo. This year we focus on the urban Indian experience — episodes of removal and relocation. The Long Walk was the first in a series which include the boarding-school projects run by the BIA and the vocational training programs that began in the 1950s that moved Indians off the homeland and into the cities.”

Durango poet Christie Ferrato is working on a project titled, “Erasure Treaty” – erasing selected parts of the Treaty of 1868 which emancipated the captive Navajos living at Bosque Redondo and released them to return back to Dinetah (the Navajo homeland).

“Largely, the Long Walk has been ignored,” Ferrato said. “You would be hard-pressed to find any mention of the Long Walk in any public-school history textbook. We just don’t talk about it. When most people think about American history in the mid- 1800s, they think Civil War and slavery. Only a small percentage of people outside the Navajo Nation know about the Long Walk, know about Native Americans being held as slaves, know about the scorched-earth campaign, or the annihilation of thousands of Navajos.”