|

Related stories |

Natural gas is the cleanest fossil fuel, at least in terms of the emissions given off when it’s burned.

But getting it out of the ground is a dirty business, a scientist warned a crowd of about 30 on April 24 in Cortez.

Chemicals used in natural-gas production can cause adverse health effects ranging from respiratory problems to skin and eye irritation to developmental defects in unborn children, said Theo Colborn, a former advisor to the Environmental Protection Agency and winner of the Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Council for Science and the Environment.

“These chemicals are not nice,” she said.

Colborn is president of TEDX, the Endocrine Disruption Exchange, a Paonia, Colo.-based nonprofit that focuses primarily on health and environmental problems caused by lowdose exposure to chemicals that interfere with development and function, called endocrine disruptors. Her presentation was sponsored by the Southwest Colorado Greens.

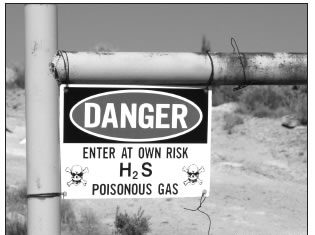

Toxic hydrogen sulfide is sometimes associated with natural gas and can be released during “flaring,” when excess gas is burned off because it is not economically feasible to collect it. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga.

Pollution is produced and toxic chemicals are involved in every phase of natural-gas production, she said.

When wells are drilled, the waste sludge containing underground muds, bit cuttings, hydrocarbons and fluids from the drilling is put in pits on the surface. The pits have been known to kill birds and other wildlife that venture into them. The pits are supposed to be shut down 30 days after drilling ceases, Colborn says, but even when the material is bulldozed over, it can migrate.

After a well is drilled, fracturing (also called “fracking” or “stimulation”) is commonly done. In that process, fluid under high pressure is injected underground, fracturing the rock layers and facilitating the release of the natural gas or oil.

“It takes 1 million gallons of fluid per frac,” Colborn said. Not all the fluid used in fracking is recovered, and it contains toxic chemicals including diesel that can migrate, potentially contaminating drinking water.

Drilling and then running an oil or gas well takes plenty of energy itself. Trucks, rigs and pumps burn diesel, producing considerable nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds, which in the present of sunlight combine to make ozone.

When ozone is inhaled deep into the lungs, it burns the tissue, causing permanent damage, Colborn said.

“You cannot repair it,” she said. “Eventually, exposure to ozone leads to asthma and chronic pulmonary disease and cardiac problems.”

Ozone concentrations are rising on Colorado’s Western Slope, she said, even as urban, Front Range areas work to bring their traffic-produced ozone levels down.

“In the East they call it ozone; in the West we call it haze,” she said.

|

What is ‘gas’? Natural gas, which is colorless and odorless when pure, is very clean-burning compared to other fossil fuels. Natural gas has nothing to do with the “gas” (gasoline) used by cars. In its purest form, natural gas is almost pure methane. Found in reservoirs beneath the earth’s surface, it is usually associated with oil deposits. Underground coal seams often contain natural gas, which in that situation is called coalbed methane. Once considered a danger and a nuisance by the coal-mining industry, coalbed methane is now quite lucrative. It can be extracted from coal deposits and sent into natural-gas pipelines. Unlike much conventional natural gas, coalbed methane contains very few heavier hydrocarbons such as propane or butane, and no hydrogen sulfide. Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a gas, but has no relation to petroleum products other than the fact that it is used to help derive more oil from oil wells. Information from naturalgas.org and Wikipedia. |

Ozone is a problem even in winter, when the extreme light reflected off snow enhances ozone production. Sunlight Ski Area near Aspen exceeded federal ozone safety levels three times last year, she said.

Ozone also invades the needles of conifers and is “death on aspen,” she said.

Compressors produce nitrogen oxides. According to the San Juan Citizens Alliance, an estimated 73,565 tons per year of nitrogen oxides are expected to be in the air by the year 2023 from natural-gas production (over 12,000 wellhead compressors) on public lands in northern New Mexico’s San Juan Basin. This represents more pollution than that emitted by the PNM San Juan Generating Station and APS Four Corners coalfired power plants, combined.

“What are we doing to our precious environment in the West, that’s already pretty harsh?” Colborn asked.

There are more problems involved with natural-gas production, she said. The gas must go through a dehydrator. Compressors are used to pressurize it and get it into the pipelines. “Every one of these things – the pipelines, compressors and so on — is leaking gases constantly,” Colborn said.

Methanol must be used to keep pipelines from freezing. In addition, workers use surfactants, lubricants, foamers, plastics, barium-laden material, and biocides to kill bacteria which could damage the pipelines. The biocides are quite toxic — “you don’t want them on your front yard or on your skin,” she said.

Ninety-three percent of the 215 products (which contain at least 278 different chemicals) used in Colorado for natural-gas production have adverse health effects, Colborn said. And of those that do, 81 percent have four to 14 different effects apiece.

Some 70 percent of the chemicals can adversely affect skin, eyes and sensory organs, she said. Next most likely to be affected are the respiratory system, gastrointestinal organs and liver, and the brain and nervous system.

But manufacturers’ Material Safety Data Sheets, which give information about product composition, sometimes just say the ingredients are “proprietary” or give vague descriptions such as “polymer,” Colborn said. Also, the sheets are mainly designed to delineate dangers involved in spills or similar accidental exposure rather than effects of long-term exposure.

Then there’s the problem of waste.

Dr. Theo Colborn, president of the Endocrine Disruption Exchange, gave a talk April 24 in Cortez warning of potential health hazards associated with natural-gas development. Photo by Graham Johnson.

Much of the fluid used in fracking is recovered. The recovered fluid may be reinjected on-site. Sometimes it is put into surface pits and allowed to evaporate, meaning that some toxic, volatile chemicals are released into the air. The residue left in the pits is taken away and either reinjected into the ground elsewhere, or “land-farmed,” mixed into soil so the chemicals can break down naturally.

The problem with the latter, Colborn said, is that the waste contains biocides that kill soil bacteria and plants. In addition, it may contain microfine particles of silica, which when inhaled is more dangerous than asbestos.

Water removed from the natural gas before it is transported is either reinjected on-site, reinjected elsewhere, or taken to open evaporation pits, which again can release volatile, toxic chemicals.

In New Mexico, 51 chemicals known to be present in such pits have adverse health effects. Some 90 percent of the chemicals in those pits are on the EPA’s Superfund list, she said.

Following Colborn’s presentation, a man who identified himself as a supervisor with D.J. Simmons, an independent oil and gas company headquartered in Farmington, N.M., questioned her statements.

“If all this is true,” he asked, “why aren’t people in Farmington dropping dead?”

A physician in the audience responded that Farmington does have elevated rates of cancer, respiratory problems and other diseases. Colborn added that many of the chemicals she discussed were not in use by the industry 10 years ago and their adverse health effects may not occur immediately.

“What are we supposed to do, go back to burning wood?” the man asked.

Mary Bachran, senior research associate with TEDX, responded, “Do it better. There are lots of things the gas industry can do to make it safer. Yes, if we stopped all this tomorrow, the economy would crash and we’d be in a world of hurt.”

Colborn added that wells are being drilled closer to each other than in the past. “We’re doing too much in too little space,” she said. “The environment can’t assimilate all this stuff.”

Colborn called for full disclosure from the oil and gas industry of all products it uses in exploration, drilling and production.

She said Colorado’s citizens must demand that new oil and gas regulations being written now [see http://oilgas.state.co.us] require full disclosure of chemicals used by the industry. Questions that need to be answered include every chemical used in drilling and production, the quantity and concentrations of those chemicals, how much fluid is recovered from operations, what is in the pits, and the amount and source of water used in oil and gas wells.

“Companies need clean water for drilling,” she said. “Where is the water coming from? A lot is taken from tributaries of the Colorado River. What does that do to the Colorado River Compact?”

Colborn recommended baseline monitoring of water quality and ozone levels before drilling begins, as well as monitoring during operations. She also recommended examining the issues of long-term depletion of drinking-water and agricultural-water supplies.

For more information, go to www.endocrinedisruption.com, and look under “Chemicals and Natural Gas.”