When Mike Muñoz was five and his father Victor was still around, Mike begged to visit Disneyland. Not just for the rides or the other attractions, but for the beautiful landscaping – “the big, perfectly-formed Donald Duck- and Pluto-shaped bushes, the vibrant floral beds depicting Mickey and Minnie, and the impeccably manicured lawns” – he’d seen on a promotional video his mother once brought home from the public library.

One day Victor, worn down by his son’s incessant pleading, orders Mike into the family car. They leave their home near Seattle, stop at the minimart for a beer, and head south toward the Happiest Place on Earth. A few miles later near the old naval shipyard, Victor parks on a deserted side street. “C’mon,” he says, stashing his empty beer can under the seat. Father and son then walk to a chain link fence overlooking an empty expanse of concrete.

“Well,” Victor says, drawing on a cigarette. “Looks like they moved. C’mon, let’s get out of here.”

“Well,” Victor says, drawing on a cigarette. “Looks like they moved. C’mon, let’s get out of here.”

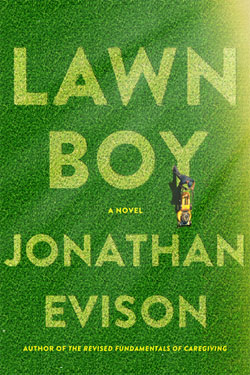

Such was Mike’s childhood. And such is author Jonathan Evison’s masterly evocation of that childhood and the hardscrabble young-adulthood that follows in his moving, hilarious, and uplifting fifth novel Lawn Boy.

Now in his twenties, Mike still lives at home with his thrice-divorced mother and his special-needs brother, the former a cocktail waitress and the latter a three-hundred-pound toddler. When he’s not unemployed, which is depressingly often, Mike scratches out a subsistence living as a gardener. What he really craves, though, is a nice fat slice of that uniquely American pie of reinvention and the comfort and security it portends, both for himself and for his struggling family. Or maybe it’s to write the Great American Landscaping Novel. Or is it to stretch his wings as a topiary artist? Or would he settle for a date with Remy, a local waitress over whom he incessantly moons?

Who knows? Which is precisely the point of a novel about a young man adrift, searching both for himself and for his place in a consumer-driven culture where the millstones of race and parentage, circumstance and poverty seem hopelessly stacked upon him. Mike is, as that childhood vignette suggests, perpetually on the outside, peering through a fence that separates his verdurous dreams from his gray and barren reality.

Readers of this column already know my deep admiration of Evison’s writing, starting with his spectacular debut All About Lulu and including the New York Times bestseller West of Here, The Revised Fundamentals of Caregiving, and This is Your Live, Harriet Chance! And while Lawn Boy’s themes of longing and self-discovery are of a piece with its forebears, it also represents something of a departure.

Here Mike’s first-person narration is simple, his language unadorned. He is neither formally educated nor sophisticated in any conventional sense of the word. His humor can be crude, and at times sophomoric. There are no linguistic pyrotechnics in Lawn Boy ($26.95, from Algonquin), and no philosophical forays. What we get is the literary equivalent of plain text – the straightforward tale of a likeable young man raised in poverty who struggles to claw his way out:

“When Mom emerged from the kitchen, tumbler in hand, she sat in the old brown La-Z-Boy that used to be Ronnie’s. She picked up the remote and turned on the TV to nothing in particular, firing up a fresh heater and drawing deeply from it. Maybe it was just the sickly light from the TV, but behind her veil of smoke she looked a thousand years old. You could see the new crown on her front tooth and how it was whiter than everything else – and it ought to be for six hundred bucks.”

The genius of the novel, and of its author, lies in the complexity of emotions Mike’s journey evokes, both from its hopeful beginning to its unexpected fulfillment. But it’s also in the nature of that fulfillment – in the subtle sleight of hand Evison works to show that the grass can be greener on either side of the fence.

Chuck Greaves is a member of the National Book Critics Circle and the author of five novels, most recently Tom & Lucky (Bloomsbury). You can visit him at www.chuckgreaves.com.