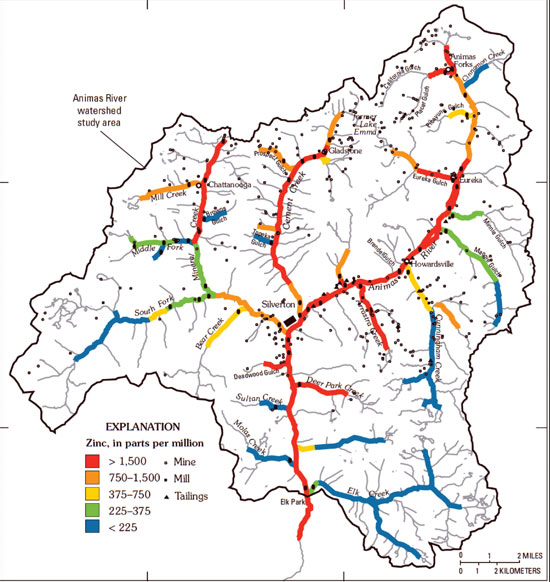

This map shows concentrations of zinc, a heavy metal toxic to fish that is a good indicator of the presence of other metals, in the upper Animas River and its tributaries. The black dots represent mines, mills, and tailings

piles. Note that some stream segments have low zinc loads despite the presence of mines. US Geological Survey

What if ?

The audience at the San Juan Citizens Alliance’s Green Business Roundtable Luncheon in Durango on April 11 was left with that question following a presentation by Jonathan P. Thompson.

Thompson, a fifth-generation Colorado native and part-time resident of Durango, was speaking as part of a book tour for River of Lost Souls: The Science, Politics and Greed behind the Gold King Mine Disaster (Torrey Press) which came out in February.

During the roundtable presentation, Thompson outlined five areas on which his book focuses: acid mine drainage, mine tailings, uranium tailings, the Four Corners Power Plant, and emissions from oil and gas fields, including the methane hot spot over the Four Corners region.

The son of the late Crow Canyon Archaeological Center director Ian “Sandy” Thompson, Jonathan Thompson weaves stories of his ancestors’ experiences settling in the Animas River Valley into a narrative documenting the history of human settlement, activity and mining in Southwest Colorado.

But the book is not only for those with an interest in the region, or mining, or Durango. It is a comprehensive and detailed account of human attempts to conquer a rugged environment, including victories, struggles, economic booms and busts, and unforeseeable tragedy. “My intent is to show how the Animas River watershed is just a microcosm of the entire West,” Thompson said.

Researching the book took years. Thompson said he has circled around the topic for more than two decades in his roles as a writer and editor. He served as editor in chief for High Country News from 2007-10, and earlier as the owner of The Mountain Journal, which he created and merged with the Silverton Standard & The Miner, Silverton’s weekly newspaper since 1875.

The history of resource extraction in the Mountain West may not be at the top of your reading list, but Thompson captures readers’ attention by bringing to life individuals and activities associated with mining in the Silverton caldera. He links those events to contemporary lives and concerns via the Gold King Mine spill in August 2015 that turned the Animas River orange and made national headlines.

Thompson admires and respects some of the early miners, investors, and developers, even though he may not agree with all their actions. He describes the intelligence and creativity the miners displayed in the early days – like Edward Stoiber, the German engineer who ran the Silver Lake mine and built a mill in 1890 on the lake’s shores in order to process lower-grade ore.

Thompson’s question “What if ?” is applied to the ingenuity, hard work, creativity and innovation of the early settlers and miners. “What if they had devoted some of their smarts, money and energy to mine more cleanly?” he asked. Thompson was struck by how the early miners and developers overcame apparently insurmountable difficulties – avalanches, extreme cold, remote high-altitude locations – in their zeal to make more and more money.

Thompson’s question “What if ?” is applied to the ingenuity, hard work, creativity and innovation of the early settlers and miners. “What if they had devoted some of their smarts, money and energy to mine more cleanly?” he asked. Thompson was struck by how the early miners and developers overcame apparently insurmountable difficulties – avalanches, extreme cold, remote high-altitude locations – in their zeal to make more and more money.

He also observes that when mining companies were required to regulate some of their waste – toxic tailings, for instance – they were able to do so successfully.

Thompson is in favor of more strictly regulating extractive industries. “Why can’t they use a little bit of the energy they used to come up with fracking to figure out how to do it cleanly?” He said that with regulation, methane leaks resulting from oil and gas production can be captured, a benefit to everyone. “There is a new industry around the clean-up of the methane leaks inspired by laws and regulations,” he said.

Thompson said his motivation to write the book was not to expose only the “doom and gloom” aspect of the region’s past. “It is not my intent to bring down land prices in Durango,” chuckled Thompson, “even though a big part of the history is dirty.”

His interest is in keeping Durango and the Animas River Valley – and the entire watershed – cleaner and more sustainable.

“Part of what makes this area so great is the extractive industries,” said Thompson. Given that what happened in the past can’t be changed, he asks, “How do we use the energy associated with the Gold King spill to make this area a better place?” Thompson uses stories in his book to draw attention to how human behaviors that ultimately led to the 2015 spill are alive and well today. There is a common perception that “back then,” people didn’t really know the impact they were having on the environment, he said, but this is untrue. Actually, the early miners did know they were polluting, but they had the idea that once an area was already polluted, there was no point in cleaning it up.

“They’ve polluted it a little bit, so let’s go ahead and pollute it some more,” is an idea still alive and well today, said Thompson.

This manner of thinking leads to the development of “sacrifice zones” (including the Silverton Caldera, the Animas River and the San Juan Basin) that are developed heavily, perhaps in order to save someplace else.

Mine tailings are a great example. Originally, all mine tailings – material Thompson says is called “slime” – were just dumped into nearby creeks and rivers, adding zinc, lead, mercury, copper and lead as well as sulfuric acid to the drainages. This was common practice all over the West, and still is in some places.

In Colorado, farmers on the Front Range noticed the deleterious impacts of the toxic sludge and began pushing back in the 1880s, which is when the subject of hazardous mine tailings became a topic for newspapermen.

Local controversies pitting farmers and ranchers against miners broke out in places such as Aspen, Clear Creek and Telluride, where the owners of the Ames electric plant (still in operation today) sued an upstream mill operator because the tailings were mucking up its operations.

Electricity generated by the Ames plant lit up Telluride and was “the first large-scale commercial application of AC power.” In 1897 the Colorado State Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Ames, requiring mills to use “reasonable means” to prevent tailings from getting into streams.

But mill owners all over the state didn’t really change their ways because of that ruling, and the battle against mine pollution continued to pit farmers, ranchers and individual citizens against the miners, engineers, developers and politicians who stood to benefit from the profits.

Newspapermen also got involved in the controversy, and Thompson brings this to life with an account of David F. Day, who founded the Durango Democrat in 1892. Day “kept flogging at the mine owners for months,” writes Thompson, but the pollution in the Animas River just grew worse, so that by 1902 the City of Durango gave up trying to keep the Animas clean and bought water rights on the Florida River.

Up in Silverton, efforts to clean up mine tailings were unpopular, as evidenced more recently by the reluctance to agree to a Superfund cleanup.

But in 1902, mine owners and residents argued that clean-up would kill the goose that laid the golden egg.

Thompson explains the “bizarre” logic: “Mine owners and their surrogates admitted to poisoning the waters. But they argued that any ill effects felt by those downstream are offset by economics. Jobs are more important than health, gold is more valuable than water, and profit trumps everything.”

This attitude is still alive today, says Thompson, citing examples from natural- gas development in the region.

But he is hopeful. Increased awareness of mining’s impact on the regional environment is an important step towards improving it, according to Thompson. What if companies actually took care of the toxins they produced in the process of resource extraction? What if citizens really knew what they were exposed to as a result of mining? What if the energy industries were regulated in a way that minimized pollution?

“Why wait until the damage is done?” asked Thompson.

In his role as environmental author and journalist, Thompson is dedicated to providing information to educate the public. The book is an easy and informative read about complex subjects. He supplements the text with numerous graphs, maps, photos and explanations on his website, which can help readers understand what exactly happened at the Gold King Mine on Aug. 5, 2015.

The audience at Thompson’s talk seemed a little stunned by the extent of the regional pollution he described. Acid mine drainage in the Animas River. Radioactive uranium tailings and mine sludge used as topsoil, and to pave roads and build basements in Durango.

A methane hot spot over the Four Corners. Coal combustion at the San Juan Generating Station causing acid rain and resulting in high levels of mercury at Molas Pass. Natural gas pipeline and well explosions in residential areas. Native farmers unable to grow crops because of toxic irrigation water. “We’re all downstreamers” is the last chapter of the book.

One audience member asked, “How safe is it to live here?” amid laughter.

“I think maybe Durango is not as healthy as it could be,” said Thompson, “but it is a fabulous place to live. I think it’s safe.”

Will there be another Animas River spill? Probably. If not the Animas, perhaps in a river in Utah, Montana, or Wyoming. “The spill was a catalyst,” said Thompson. “The point I want to make is that the spill is not extraordinary. The Animas River is a microcosm of the entire West.”