The Bears Ears National Monument Advisory Committee will meet in Monticello, Utah, on Feb. 25. This is the second meeting of the committee, which met for the first time in June 2019. Thirty minutes each day are allocated for public comments.

The Bears Ears National Monument Advisory Committee will meet in Monticello, Utah, on Feb. 25. This is the second meeting of the committee, which met for the first time in June 2019. Thirty minutes each day are allocated for public comments.

But what is a citizen supposed to comment about and how would anyone know what is going on right now?

The intent of the Monument Advisory Committee meeting, as stated in the agenda, is to “provide information on how MAC member input was used in the planning process” as well as to update members on the monument’s status and “review and refresh” the committee’s roles and responsibilities.

According to San Juan County Commissioner Bruce Adams, chairperson of the committee, “All we’re going to do is advise how to implement the decision already made by the BLM.”

The lands now referred as Bears Ears (named after two prominent buttes) are located in Southeast Utah, primarily within San Juan County, and contain spectacular scenery including red rock canyons, snowy mountain vistas and piñon and juniper clad plateaus. It is the landscape some came to know from reading Edward Abbey’s classic work, Desert Solitaire, and others by visiting Utah’s “big five” national parks: Arches, Canyonlands, Zion, Bryce Canyon and Capitol Reef, all in this southeastern part of the state. River runners, mountain bikers, backpackers and rock climbers negotiate slot canyons and remote trails, while ATV/OHV enthusiasts enjoy exploring the remote lands on empty roads. Even houseboaters floating through Lake Powell are keen on the area. Clearly it is a recreational dreamland.

The Antiquities Act

Adding interest and complexity to the region is the fact that thousands of archaeological sites are located here, many important to contemporary Native Americans. These cultural resources are what initiated the most recent effort to increase legal protection for the area, since looting and pothunting have been on the rise.

According to an article in the Durango Herald in May 2016, “between October 2011 and April 2016, the BLM’s field office in Monticello investigated 25 cases of looting, vandalism and disturbance of human remains in San Juan County.” Some of the cases included desecration of burial sites and campers and hikers destroying prehistoric walls, tearing down a historic Navajo hogan, and building fire pits with building blocks extracted from ruins. Pictograph and petroglyph panels have been vandalized, with people scratching their names in the walls, removing rock art, and writing or painting on the panels.

The Antiquities Act of 1906 was President Teddy Roosevelt’s response to pothunting, which was as popular in his day as it seems to be today. The act has three parts, the first stating that “any person who shall appropriate, excavate, injure, or destroy any historic or prehistoric ruin or monument, or any object of antiquity, situated on lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States”can be fined or imprisoned.

The second part gives a sitting president the power to establish a national monument, stating “That the President of the United States is hereby authorized, in his discretion, to declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments.”

The third part gives the Secretary of the Interior the power to grant permits to people who do want to excavate archaeological sites and “gather objects of antiquity” and gives the Secretary power to decide who is qualified to get these permits.

In the 114 years since it was established, the Antiquities Act has been used by every president except Reagan, Nixon and George H.W. Bush.

Teddy Roosevelt established 18 national monuments, including Grand Canyon, Devil’s Tower, Chaco, and the Petrified Forest Other places now known as national parks, including Acadia, Grand Teton, and Olympic, started as monuments.

Although a sitting president can set aside a monument by presidential decree, national parks are created only through acts of Congress. National monuments and parks differ according to why they have been set aside. National parks are dedicated to “conserving unimpaired” scenic, recreational, inspirational and educational purposes and natural and cultural resources. Conservation and recreation are key.

National monuments are established to “sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.” While they do attempt to preserve resources, existing uses of the land, such as grazing, timber harvesting, oil and gas exploration, hunting, fishing and outfitting are all allowed.

Basically this means that anyone who was using the lands prior to a monument designation will keep their rights. OHVs and mountain bikes are allowed on approved roads and trails, but development of new routes for motorized vehicles is only for public safety or conservation of the monument’s resources.

Presidential back and forth

The tension between preservation and multiple use in the management of national monuments is fraught with political repercussions, as evidenced by the controversies

and confusion associated with Bears Ears. In 2015, the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition was formed in response to the increased desecration of important and sacred cultural sites in the region. The coalition consists of leaders from the Hopi, Navajo, Ute Mountain Ute, Pueblo of Zuni and Ute Indian tribes, and is an unprecedented tribal collaboration. They joined with conservation groups to submit a proposal for a national monument to President Obama which included 1.9 million acres of ancestral lands under federal jurisdiction on the Colorado Plateau, including over 100,000 documented archaeological sites. They proposed joint management between federal and tribal agencies, and had the support of 30 other tribes.

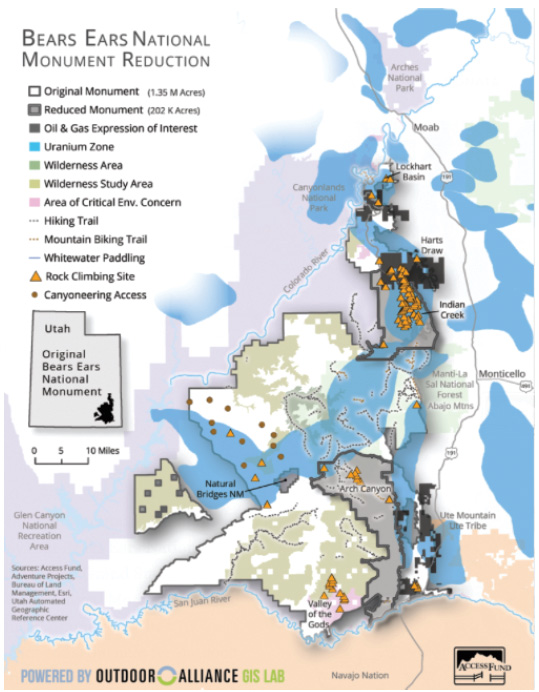

Obama established Bears Ears National Monument on Dec. 28, 2016. His proclamation included most of the area proposed by the tribal coalition: 1.35 million acres – over 2000 square miles of federal lands.

The proclamation details the rich natural, cultural, geologic, and archaeological resources, reading somewhat like an essay by Aldo Leopold or John Muir, referencing carnivores, eagles, serviceberry. “A few populations of the rare Kachina daisy, endemic to the Colorado Plateau, hide in shaded seeps and alcoves of the area’s canyons,” it states. And, “Throughout the region, many landscape features, such as Comb Ridge, the San Juan River, and Cedar Mesa, are closely tied to native stories of creation, danger, protection, and healing.”

Eric Descheenie, who once led the intertribal coalition, was quoted in the Atlantic a few days after Obama’s declaration, saying, “It actually brought tears to my face. It’s so significant.”

Oil and gas interests?

Not everyone was thrilled, however. Then-candidate Trump seized upon Bears Ears as a key issue of his campaign, vowing to undo what Obama had done, and he followed through almost a year to the date after Obama established the monument.

“It is in the public interest to modify the boundaries of the monument to exclude from its designation and reservation approximately 1,150,860 acres of land that I find are unnecessary for the care and management of the objects to be protected within the monument,” reads Trump’s Dec. 4, 2017, proclamation.

The reduction in size of Bears Ears opens up the protected lands to oil and gas development and mining.

Three days after Trump’s proclamation the Washington Post published an article headlined, “Areas cut out of Utah monuments are rich in oil, coal uranium.” It stated that “BLM maps show high-to-moderate oil and gas development potential in much of the original Bears Ears footprint, and most of the areas thought to have the most oil and gas — and the few existing drilling leases — are outside the new boundaries, according to the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance.”

Turns out this is not just conjecture. In 2018, the New York Times sued the Interior Department for access to emails that showed Trump was interested in the energy development potential of the lands within the original monument, which is why he shrank the boundaries by 85 percent.

A Times article outlines a series of communications going on behind the scenes for over a year between Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch and then-Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, detailing the coal, uranium and oil deposits and suggesting new boundaries for the Bears Ears monument as well as Grand Staircase- Escalante National Monument (which sits on the Kaiparowits plateau coal deposits.) The new boundaries in Trump’s proclamation corresponded with those suggested by Zinke, and essentially paved the way for increased resource extraction in what was once the national monument.

Lawsuits

A coalition of tribal entities and local, regional and national conservation groups has challenged the reduction in size of Bears Ears National Monument in federal court. This lawsuit includes three challenges brought by 24 different entities, including tribes, recreationists, archaeologists, paleontologists, historians, and wilderness groups. They asserted that the Trump administration exceeded its authority by shrinking the monument, arguing that only Congress can amend the boundaries of an existing monument.

The Trump administration fired back with an order to dismiss the case, insisting that the Antiquities Act gives the president this power of proclamation and presumably reduction.

At the end of September 2019, U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan denied the motion to dismiss. Both sides are gearing up for protracted legal battles.

What does this mean currently? And what impact will this have on the upcoming BENM advisory committee meeting?

In late December 2019, the environment and energy publication Greenwire noted, “The documents show that the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia will spend the first five months of 2020 focused on dueling motions for partial summary judgment in the cases. Both sides will ask the court to determine whether the Trump administration acted legally when it determined the president could use the Antiquities Act of 1906 to shrink the monuments.” According to court documents, motions will be filed in early February, and “subsequent replies” are scheduled through May 2020.

Committee meeting

Meanwhile both uncertainty and business as usual prevail. The monument currently stands as reduced by Trump into two sections known as the Indian Creek and Shash Jáa units, which are managed jointly by the BLM and U.S. Forest Service. The Shash Jáa Unit contains 97,393 acres of BLM-administered lands and 32,587 acres of USFS-administered lands and the Indian Creek Unit contains 71,896 acres of BLM land.

The Monument Advisory Committee was set up to implement the management plan, which the Forest Service and BLM have spent the past six months developing.

At the upcoming meeting in February volunteer members will review the management plan and be updated on any new developments.

Adams thinks that the advisory committee is “diluted.”

“It’s a pretty watered-down committee,” he said. “They’ve already written the plan – we don’t get involved with the plan. Not a lot of local input.”

When asked what he thought the upcoming meeting would be about, he responded, “Maybe it will be something to do with how they’re going to address parking needs, restrooms, or trails with kiosk information to tell people how to act on the monument once they’re on it.”

The meeting agenda states that cultural resources, recreation and travel management planning will be addressed so that the committee can give feedback to the BLM on these topics. Adams said he’ll be surprised if anyone shows up to comment, noting that “most of the decisions have been made.”

The meeting agenda repeatedly states that the purpose is to discuss “implementationlevel planning.”

The BLM contact person for the committee refused to answer any questions about the upcoming meeting, deferring instead to a “media contact person” who provided web links rather than comments.

Meanwhile the BLM continues to offer oil and gas leases on lands that used to be in the original Bears Ears National Monument. The legal battle continues.

Heidi McIntosh, Earthjustice attorney involved in the litigation, is quoted on the Earthjustice website as saying she looks forward to showing that President Trump violated the law when he dismantled Bears Ears. “We will work relentlessly until we ensure that Bears Ears and Grand Staircase are protected forever as they were meant to be,” she said.

The advisory committee meeting will take place Tuesday, Feb. 25, from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. at the Hideout Community Center, 648 S. Hideout Way in Monticello.

Public comments are scheduled for 2 p.m. and anyone wishing to comment must sign up first.