Basically, everyone in Montezuma County depends upon one source of water: runoff from the snowpack in the San Juan Mountains.

It flows primarily into the Dolores River, but also the Mancos River and tributary streams including Horse Creek, Turkey Creek, Plateau Creek, House Creek, Dry Creek, Beaver Creek, Lost Canyon Creek and more. Other sources include wells and springs.

“Whiskey’s for drinking and water is for fighting.”

The old saying probably comes from the fact that although we all may depend upon a single source of water, what happens when we start utilizing that water is an entirely different story. According to the Colorado constitution, all water in a stream is considered the property of the people of Colorado – however, the state does not guarantee the right of an individual to use that water.

The right to use water depends upon a complex system of allocation and appropriation, contingent upon factors such as water source, time of initial use and type of use.

Water in Colorado is categorized according to where it comes from and how it is used. Surface water includes all water flowing in rivers, streams, springs and ditches, and is classified as being either adjudicated, project or unappropriated.

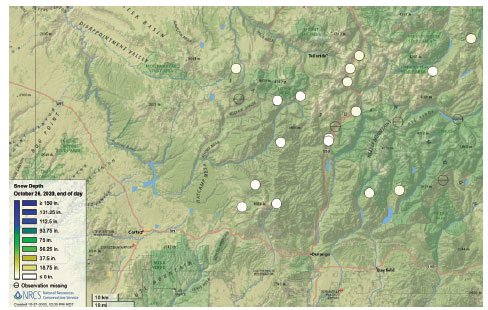

Sno-Tel sites in the local watershed are showing low levels.

Adjudicated water has been decreed by the Colorado Water Court for use by certain individuals or their successors.

Project water has been federally classified as “irrigable” and is impounded by a dam or other projects for agricultural use.

Project water is “allocated” to a particular acreage or user.

Finally, water that has not been adjudicated is determined to be “unappropriated” and is the water that is still available for use.

Water that is “appropriated” is adjudicated water that has been determined for “beneficial use” by the water court. Beneficial uses include domestic, agricultural and industrial use. Domestic use can be drinking, household use, irrigating lawns and gardens, maintaining parks, fighting fires, and recreation. Agricultural use is for crops and livestock and industrial use is for mining, processing natural resources, production of power and manufacturing products.

In a shortage, domestic use takes priority over all other uses, with industrial usage the last priority.

Groundwater is water that is contained in the pore spaces of soil or rock below the surface, and includes aquifers. It is classified according to whether or not it is tributary to a natural stream, or non-tributary. Tributary means the groundwater seeps into natural streams, while non-tributary means it does not.

These categories are subject to different regulations, with tributary water determined as either “exempt” from statutory regulation, or “non-exempt.”

These terms are applied to wells. Anyone applying for a well permit has to demonstrate that the water is not already allocated to someone else. Groundwater administration and enforcement is one of the primary responsibilities of the Colorado Division of Water Resources.

All water in Colorado, whether surface or ground, is allocated according to a “priority” system of water rights, with a “right” meaning an appropriator can use the water for a beneficial purpose as long as they need to for that beneficial use. Often referred to as ‘first in time, first in right,” it means those who take the water first get to use it first. Water rights are described as “senior” or “junior” in this system, with senior rights meaning the older rights.

Water rights also determine the quantity of water the user/appropriator may divert. In the priority system, water rights are recorded by including a date that the water was first put to beneficial use, as well as how much water the appropriator is entitled to – the lower the number, the more senior the water right is. For instance, the Mancos River Critical Reach Priority list begins with water right M-1, #8948, which is the Giles Ditch. It has an allocation of 2 cfs, established in 1893.

In 1963 another 3 cfs was added to the Giles Ditch with a priority number of 62. Thus, anyone owning water rights on the Giles Ditch is entitled to 5 cfs of water. If the owner does not receive all 5 cfs at any given time, they can put a “call” on the water for 2 cfs, which will supersede anyone else’s rights since it is senior right #1. A “call” means that when the water user with the priority “senior” right does not get their allocation, they can require that other more junior right users stop diverting water until the senior user receives their full allocation.

Confused? It gets worse! Water rights are real property rights protected by Colorado and U.S. constitutional law, and can be used, sold, given away or used as collateral. They are not tied to any piece of land. They can be transferred, rented, and exchanged, and these transfers have to ensure that no other rights are impacted.

This ends up leading to a lot of disputes and legal settlements, which keeps water lawyers in business. Surface water – which is flowing – is measured in cfs (cubic feet per second) which refers to the volume of water flowing by a certain point in one second. One cfs is equal to a flow of 448 gallons per minute.

Project water, usually contained in reservoirs, is measured in acre-feet, meaning the volume of water needed to cover an acre of land to a depth of one foot. One cfs flowing for 12 hours is equal to 1 acre-foot of water, and 1 acre-foot is 325,851 gallons.

Adding to the complexity is the fact that project water locally is distributed by various entities, all of which have different regulations and stipulations on water use, although all must adhere to Colorado water law.

There are at least five different water-management companies in Montezuma County, each owning and operating different water sources – including both surface and project water – and distributing it according to the desires of the water-using members, which also differ.

Montezuma Valley Irrigation Company (MVIC), one of the oldest companies, is a “mutual ditch company,” which owns consolidated water rights as a non-profit corporation. According to their website, ditch company members own shares in the company which provide them with a specified amount of water from the pool of water controlled by the company. This is a typical arrangement.

Wendy Weygant of MVIC told the Four Corners Free Press that “in 2019, we had 33,284 shares and there were 1455 accounts.” No half shares are allowed, and shareholders determine the assessments, which were $30.50 per share this year, paid annually. Water is only delivered to accounts that are paid in full. A share is usually 4 acre-feet, but this year members reduced the allocation to 3 AF because of drought conditions.

“In a short season we are mandated to allocate down to the fish pool – while in a good season we can hold some water back,” Weygant said. “This year we were short. The problem was that the moisture was good down here, but Groundhog Reservoir didn’t get the snowmelt we needed. It depends on how the snow comes off. If it comes off too fast, we are not able to hold everything in Narraguinnep, and we lose it. There’s a lot of variables which influence how much water we have.”

Variables not only impact the runoff and how much water is available for storage, but impact each separate water entity as well. For instance, one MVIC share is 5.62 gallons per minute, while one share for the members of the Summit Reservoir and Irrigation Company (SRIC) is 37.3 gallons per minute. The SRIC has 147 members owning 400 shares, and members can own half shares.

The Montezuma Water Company has 5000 members and water is assessed at $3.60 per thousand gallons.

Since each not-for-profit water distribution company is member-owned and operated, and since they draw water from differing sources- both surface and groundwater, there is no consistency among them regarding what constitutes a share, how much shares cost, or how many shares members can have. The only consistencies are the Colorado water laws that all must abide by.

Adding to the complexity is the fact that besides transferring water rights, individuals and groups of water users can apply for new well permits and water rights.

“As of today you can get a 2020 water right, but the chances of ever getting any water is slim,” said Gary Kennedy, superintendent of the Mancos Water Conservancy District.

“The Mancos River is already over-allocated, meaning there are people that have water rights on the Mancos River but they typically can’t get it because it’s only there in the very few years when we have tremendous snowpack and runoff.”