Early in the 1990s, Tremayne Cleveland and his cousin brothers and sisters used to climb in the back of their Grandpa John Tso’s pickup to visit Mr. Tozer in McElmo Canyon. They were headed to his watermelon patch, a short 19 miles east of their home on Cahone Mesa in the Navajo Reservation.

All the children, now in their early 20s, were under 10 in those days. They loved the trip. It was special. It was an adventure with their grandfather, fun and happy.

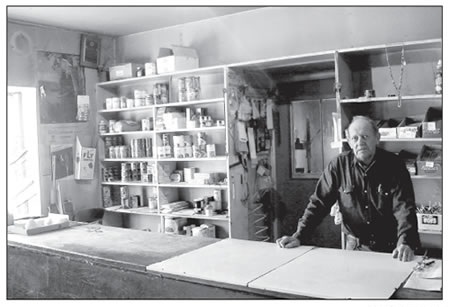

Robert Ismay is owner and proprietor of the historic Ismay Trading Post on the Utah-Colorado border. Photo by Sonja Horoshko

After the visit to Tozer’s place, they climbed back in the bed of the pickup surrounded by watermelons and other produce for the trip back home down the McElmo Canyon Road. As they neared the reservation boundary Cleveland and his brother, Cameron, would lead all the children in a chorus of their favorite tune, an original piece they called “The Ismay Song,” based on a popular Reba McEntire tune in which she sings, “I’ve been thinking about Las Vegas.”

Cleveland and his cousins substituted “Robert Ismay” for “Las Vegas,” he says, singing the rhythm in their own Ismay Song all the way to the trading post, over and over. “I’ve been thinking ’bout Rawww…bert … Izzzmayyyy….Sells peaches for 50 cents, and a Big Hunk.”

Cultural confluence

Ismay Trading Post is on the map at the confluence of McElmo and Yellow Jacket canyons. It is the last stop on the road to the Navajo reservation from the east side in Colorado. For many decades it offered one-stop shopping for people living beyond the end of the road. Customers could pick up mail, general store goods, seasonal fresh produce and flat-tire repairs all in one place.

Eleanor Heffernen Ismay, Robert’s mother, and his father, John Ismay, built the adobe trading post in 1921 with the help of Eleanor’s father, Jim Heffernen, who also built the Oljeto Trading Post, which is still in operation today.

In a 1976 oral-history recording of Eleanor Ismay, archived in the Heritage West database of historical resources, she says, “McElmo is a good place for all kinds of fruit. Ours got a blight, but our son’s grown the orchards up Yellow Jacket Canyon.”

Her story unfolds on the 30-minute mp3 as a bustling, rich, cross-cultural and knowledgeable business endeavor.

In telling the trading post’s history she describes customers at the trading post in the beginning years when, she says, the Utes “set up Tipi camps across the road in one spot or another close to the store. Although a lot of them had wagons to get around with, most rode their horses here….They were very jolly people, full of jokes. They were also very hard workers. We got along with them.”

Today, the wagons are gone, but the trading post remains.

The store sits 50 yards from the current border of the Navajo Nation. It is the closest business establishment to the reservation and still meets many needs of the people living around Aneth and Montezuma Creek in Utah. The Ismay family kept up with the times, offering goods and services reflecting changes in transportation and commerce as well as family needs.

Changing times

On this crisp October day, Leda Blackhorse Nez walks through the door to buy a bottle of water from Ismay. She moved back this year to her home on the reservation a few miles west of Ismay after spending 21 years off the reservation working at her career in elder care. She is glad to come back and happy to bring her grandson into the store where, she recalls, her mother would take her each year just before the school year would start.

“Mrs. Ismay would go to Cortez and bring down clothes for the school children. We always came here to get our new socks, shoes, underwear and this and that.” She pauses and adds, “Mrs. Ismay gave me my name. Mrs. Ismay named me Leda.”

While Nez shows the trading post to her grandson, owner and proprietor Robert Ismay reaches under the counter for a telephone. He places it on the counter in front of an elderly Navajo couple who want to make a call. It’s a beige 1960s model, the kind where the receiver is cradled in the base.

Each of them takes a turn on the phone. Their conversation, in Navajo, is soft and gentle. They hang up and let him know the phone will be ringing back for them. They’ll wait, they say, and he nods and then they spread out pocket change on the counter to pay Ismay for the call.

Land-line telephone service is sporadic even today in the Utah Navajo strip. People use cell phones now, so demand for the land line has diminished, but he still offers the service, especially for the elders, who may need the convenience of calling near home.

Over the years, gasoline also became a low-demand item at Ismay’s. Once available at two pumps in the parking outside the building, it is no longer a feasible investment, Ismay says.

“There’s a lot more traffic now, but when our gas costs more than Cortez, people buy a dollar and it’s almost not worth going out to turn it on.” A few years back Ismay took the pumps out, replacing them with a concrete barrier. The vintage metal shells now stand beside older, replaced pumps rusting in the weather behind the shop — footnotes to the Ismay story.

By the time the phone rings on the counter again, the grandmother and grandfather have waited 30 minutes for their return call on the Ismay land line. They conclude their conversation quickly. As they leave the woman turns back in to the store, saying to Nez, “Mr. Ismay can speak Navajo, too, like his father.”

It’s a compliment, but Ismay responds that he can’t, “not really, not much, but my father knew a little Navajo. He was fluent in Ute. Not many people speak Ute these days.”

Peaches and soda pop

The interior of the shop is dusty. Really dusty. The lighting is naturally dim. The shelves today offer only bare essentials — tools, enamel bowls, cold soda pop, water and ice tea, a spare selection of canned goods — beans, chili, Spam, tomatoes — stacked neatly beside noodles and flour, baking soda, oil and transmission lubricant.

Peaches grown in McElmo Canyon are the best in the region and, according to locals, the best of all peaches. In late summer customers can count on finding a box on the Ismay Trading Post counter, handlabeled, “2 for $1.”

Ismay, who grows the peaches in his own orchard, admits there are not as many now, but “in the old days the Indians would pick them real green for us. We’d sell to the trucks that took them to Oklahoma and Texas.”

A lot of the store’s merchandise is used in ceremonial life on the reservation – water buckets, rawhide for clothing, implements and drums, gourds, some weavings, cloth and wedding baskets. Although the merchandise is re-stocked often, the selection rarely changes. Even the classic turquoiseand- silver Navajo jewelry displayed under the glass counter and piñon-seed necklaces hanging above the Big Hunk candy bars look like they have been there for 20 years.

On the counter near the front door in light falling through the window there sits a box filled with empty pop cans – recycling at Ismay’s has always been part of the business.

There is no background noise, no computer or radio playing, no commercial lighting or neon “open” signs. Ismay’s polite, laconic responses — “yup,” “spoze so,” and an occasional tip of the cowboy hat and a smile — dampen the clamor and din of the modern world 30 miles up-canyon in Cortez.

Outside, a sparkling 9-foot-wide mound of broken green glass on one side of the parking lot looks like a found-art installation. “It’s one-way bottles,” says Ismay, “tossed there. When pop came in thin glass, it was always breaking…wasn’t worth taking it back for the refund.”

Ismay was one of nine children that Eleanor and John raised at the site.

In her recorded interview Eleanor describes the kids’ schooling. “Some of them went to Battlerock School,” about 14 miles up the canyon from Ismay’s, “but another one-room school was built closer … because the roads were so terrible, why, you couldn’t get there…I taught some of them at home…then I moved to Mancos for 10 years so the children could go to high school there.”

Robert Ismay continued his education at Western State College in Gunnison, Colo., majoring in history and political science with a minor in physics. He wanted to be a teacher. Two years later he enrolled, instead, in the Army anti-aircraft artillery during the Korean War for training as a radar repairman and was stationed in Seattle, where he guarded the Boeing aircraft factory until his discharge.

Of the nine children, only Robert and a sister, Laura, survive. She married Sherman Hatch and lives at Hatch Trading Post on the north side of Cahone Mesa at the mouth of Montezuma Creek Canyon, not far from Ismay. A story circulates out there that one day Sherman rode his horse over the mesas and asked for Laura’s hand in marriage and then put her on his horse and rode back over the mesa.

When asked about the story, Ismay grins widely, but says simply, “That’s not true,” and offers no further comment.

A brother, Eugene, came home to the trading post after serving in the Navy during the Korean War. They operated the store together from 1958 until Eugene passed away five years ago, leaving Robert the sole proprietor.

“A lot has changed,” he says. One facet of the business that evaporated was ice-making. “We made 1,000 pounds of ice every day using a big commercial ice machine,” Ismay recalls. “Miners and oil-field workers would buy it on their way to work. We’d cut 50-pound blocks in four so they’d fit in their boxes.” But with coolers and frozen packs readily available, the need for ice disappeared. The ice machine sits silent now covered in dust, corroded from the calcium in the water they used. Always there

When the McElmo Canyon road was paved all the way into Utah in the 1990s, it put a further dent in Ismay’s business as the drive to Cortez and its supermarkets became much faster. However, many locals still support the trading post and value its presence.

Lynne Tilsen, a resident of McElmo Canyon, says, “He’s doing something very few people do today. He’s choosing to be out there and somehow it should be important to us all.”

She overheard a woman in a Cortez coffee shop say that she feels it’s important to buy something from Ismay’s, even a bottle of water, like a toll. Tilsen agrees and recently took two visiting friends from Pennsylvania and New York out to Hovenweep National Monument via McElmo Canyon.

Before they crossed out of Colorado at the border she suggested they go into Ismay’s, advising them that they should at least buy a bottle of water. “But all of us spent quite a bit more on carved wooden figures, some pottery and beadwork, and, of course a bottle of water each.”

Many of the new customers today are coming for the archaeology. Ismay keeps a stack of academic documents behind the counter showing some of the research that’s been published about his property.

“Archaeologists started coming about two years ago,” says Ismay, pointing to a photocopies printed with fading drawings of elaborate rock art that can be found in the area. “Those figures are as tall as us,” he says quietly.

Now many generations old, the trading post feels like a throwback in time, a tableau of history. He grew up with the site, and local people respect that. Grandparents and parents introduce their children to the trading post as if it’s a safe place to begin engaging with the world beyond the reservation boundary.

Eli Tso, like others who live nearby, is careful to describe whether it’s the father or the son he’s talking about. He loved going to visit John and Eleanor Ismay with his own mother and father, and now, as an adult, he stops in almost every week with his children and grandchildren.

“When I was a teenager I’d saddle up the horse,” he recalls, “ride the reservation fence line over there, over that canyon down there,” gesturing toward the eastern edge of Cahone Mesa, “into the canyon to the back of Ismay’s at Yellow Jacket… It took 40 minutes one way to go for some pop and candy, sometimes for peaches.”

His niece, Eudora Claw, feels happy when she drives back home from graduate school in Albuquerque, N.M., through McElmo Canyon. “It just feels good when I see Ismay’s. I feel a glow inside when I pass by. I know I’m close to home.”

If you ask members of Colton Morgan’s family where they are from, they often say, “Ismay.” They live a few miles west of the trading post and their home address is Aneth, Utah, but they identify with the wellknown and beloved landmark.

Morgan, now 22, remembers when he was a student at Battlerock Charter School, 15 years ago. He remembers one morning when the whole school got on the bus to go on a field trip to the rock-art site behind Ismay. “At the end we got to go inside Ismay’s. Then I told the kids on the bus before we went in that ‘this is my place; this is my store.’ I was so proud when we walked in and Mr. Ismay remembered me.”

The trading post is 90 years old. Ismay admits to thinking about retiring, but for now, he says, he’ll just be open when he feels like it, to have something to do.

Morgan adds, “I always think he’s there. I know he’ll still be there.”

Let’s hope we’ll all be there in 2021 when Ismay Trading Post celebrates a 100-year birthday and everyone can join in a rousing round of, “We’ve been thinkin’ about Rawwwbert Izzzmayyy. . . . Sells peaches for a hundred years”