Gila Wilderness, N.M. — Wolves again roam the dense forests here, a stealthy force that restores a balance of nature between predator and prey, and less so, between man and beast. But will it last?

When in 1998 the Mexican gray wolf was returned to the Southwest under the Endangered Species Act, animals as well as people sat up and took notice. For elk, the wolves’ favorite prey, the “primeval dance was revived,” as biologists put it, altering grazing and migration habits and sparking to life a hard-wired instinct to beware of what lurks in the shadows.

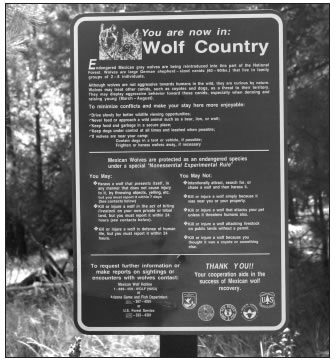

A sign outside Alpine, Ariz., in the Apache National Forest explains that wolves are protected and visitors should not harass or kill them unless threatened. Photo by Jim Mimiaga

Ranchers responded to the reintroduction with as much wariness as the elk. For ranchers, bringing back the nemesis that their fathers and grandfathers had successfully eliminated by the 1970s felt like a government betrayal of their way of life.

“Wolves do not belong here, they were removed for good reason and are no longer part of the ecosystem,” said Ed Wehrheim, a county commissioner representing ranching interests for Catron County, N.M. “The re-introduction is just something the environmentalists want to do.”

But multiple lawsuits against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to stop the Southwest wolf-recovery program have failed, and the protected wolves have been allowed to thrive, despite substantial resistance by locals.

Before pioneer days, an estimated 200,000 wolves roamed the West, according to Defenders of Wildlife, an environmental nonprofit. Today, thanks to reintroduction programs made possible by the Endangered Species Act, an estimated 1,500 wolves survive in the wild in the U.S., mostly in Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. The lesser-known Mexican wolf, a distinct subspecies of the gray wolf known locally as the lobo, survives on prime habitat spanning the New Mexico- Arizona border.

A population of 52 wolves, representing 12 packs, roams the Blue Range Wolf Recovery area, a tightly controlled boundary which includes the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest in Arizona and the Gila National Forest in New Mexico. The area also encompasses the Gila and Aldo Leopold wilderness areas. And since 2002, the neighboring White Mountain Apache Tribe in Arizona joined the recovery program by opening up its 1.6 million acres of reservation for the wolf.

The recovery goal for the program is a stable population of 100 or more wild wolves.

While the return of the lobo has attracted hikers and photographers hoping to glimpse a wolf or just hear a serenade of distant howls, safari groups and outfitters feel the wolf competes with them for the trophy elk coveted by their clients. And so, for wolves both north and south, the debate continues to howl on.

“I think societal values have changed regarding the wolf,” says Chris Bagnoli, a U.S Fish and Wildlife coordinator for the Mexican wolf program. “Before, it was all ‘protect livestock and remove predators’. Fast forward to today and values have changed; it still includes ranchers but the public also wants predators back in the landscape.”

Borderline survival

As the joke goes: Wolves don’t read the rules that spell out the political border between freedom and likely capture and relocation. Three trespass violations in a 365-day period will land a wolf back in captivity, usually at a wildlife museum in Tucson. Including the White Mountain Apache land, the Mexican gray wolf has 10,000 square miles of forests and river valleys where it can legally live within under the reintroduction program. But the area, while significant, can be a limiting factor for wolf recovery, explains John Oakleaf, Mexican wolf field coordinator for the USFWS.

“The northern gray (wolves) have several states where they can roam free and are protected,” he said. “Down here we have tighter boundaries, so this is a significant issue that makes recovery more difficult.”

Biologists want wolves to dictate where they are going to survive, but that is a challenge because “wolves follow the elk across the boundaries, and new packs looking for more territory also cross over,” Oakleaf said. He added that the boundary violations are not common, but can spike some years. One wolf, for instance, twice wandered as far as Grants, N.M., and had to be taken back into captivity.

Boundary adjustments to the wolves’ territory are considered in a public and government review of the program, currently under way. The process, called Rule Modification, requires an additional environmental impact statement that is expected to be completed no sooner than 2012.

Cooperation from the White Mountain Apache tribe has been crucial, Oakleaf said, and a “significant” portion of the wolf population survives on the reservation because of its prime habitat, sparse human presence and abundance of big game. The sovereign nation was not on board at first but has since negotiated an agreement with the USFWS that closely mirrors the government management plan.

“No matter what we did, the wolves kept wandering onto the reservation here, so the tribe decided that it was better to just accept it and manage it using our own people,” said Krista Beazley, a wolf biologist and tribal member. Trophy elk populations on the reservation have supported a healthy hunting-outfitter economy, she said, and the excellent vegetative cover of the rugged White Mountains has also benefited the wolf.

“Studies show that wolves help elk herds by weaning the weak and sick, so it is a balance that helps to stabilize the population,” she said.

Saved from extinction

Like the endangered California condor, the last of the wild Mexican gray wolves also had to be captured, bred in captivity and later released back into the wild in order to survive.

By the 1970s no wild Mexican wolves remained in the American Southwest and just a handful held out in Mexico. To prevent extinction, as required by the Endangered Species Act, five were captured in the late 1970s and put into a breeding program centered at the Wildlife Museum in Tucson. Currently there are 300 captive Mexican wolves in various zoos and reserves, representing three genetic strains.

Smaller than the celebrity northern and timber wolves of Montana, Minnesota and Canada, but packing the same physical punch, sleek Mexican grays can definitely hold their own in their historic range here.

“It’s somewhat of a myth that wolves only prey on the sick, old or weak,” says Oakleaf. “Utilizing advantageous terrain, these wolves regularly pull down healthy bulls as well.”

Pups are being born in the wild, and are proving that they can adapt to terrain and natural prey opportunities, he said. Wild-born wolves are captured when possible so they can be collared and tracked, and second-generation breeding has also proven successful. Den sites are closely monitored in the field, and supplemental food (deer carcasses) is sometimes left for mothers with pups to ensure their survival.

Since the program started, 92 wolves have been released. A dozen were killed by cars, several were illegally shot, some were euthanized for breeding with domestic dogs and still others were captured and taken back into captivity for pursuing livestock.

When wolves wander off the recovery zone, they are captured and relocated back within its boundaries. Every year carefully selected wolves, sometimes a dozen or more, are released in a primary zone around Alpine, Ariz.

Because of the small initial breeding stock, genetic variability has been a concern. Careful breeding, successful genetic research to establish additional lineages, and strategic translocation over time has increased diversity of the breed, Oakleaf said.

Overall, managers are satisfied with the program’s measured success, and after three-year and five-year reviews it was allowed to continue.

“It is rewarding because what we have here in the wild, and some breeding stock in the wildlife museum, are all that are left of these unique animals,” Oakleaf said.

Interestingly, wolves do not require a natural corridor to migrate into new territory, meaning it is possible one could migrate to Colorado, “although the rules now state we must pick them up.” Recent genetic testing of skulls found in southern Colorado and Utah confirmed they were of Mexican wolf lineage, thereby expanding the northern edge of their historic range. One northern wolf from Yellowstone migrated to forest*s around Vail, but it was promptly killed crossing Interstate 70, Colorado’s Berlin Wall for wildlife.

A wolf cafeteria?

Wolves capture the public’s imagination of a West still wild, but not everyone is so enthusiastic.

“I’d say over 90 percent of Catron County is opposed to the wolf being here,” said Ed Wehrheim, county commission chair of Catron County, population 3,500. “Our economy is mostly ranching and we feel the program is going to wipe out most of the ranching in the Southwest.”

So far five ranchers have been put out of business, he said, and more are likely to go under as the wolf pack gets larger, he said.

Government biologists say wolves occasionally kill livestock, but prefer natural game, which is abundant. How much livestock wolves kill is hotly disputed, because kills are hard to verify, occur in remote areas and may have been caused by another predator such as coyotes, cougars or black bears.

Under a program run by the USFWS, the Arizona and New Mexico departments of Game and Fish, and Defenders of Wildlife, ranchers are compensated 100 percent of the market value for a confirmed wolf livestock kill, approximately $400, and 50 percent for a probable kill. But that is not the point, critics argue.

“We’re not in business to raise wolf food,” Wehrheim says, “and that cow is worth three or four times more than the market value to a rancher who raised it and uses it for calving.”

Wolf management to control livestock depredation is a particular challenge in the Southwest, Oakleaf explained, because ranching is yearround so cattle are more exposed.

For the northern wolves the opportunity to grab some beef is slimmer because ranching operations are much more seasonal, he said.

“It is a big issue when livestock are killed because it is money out of the rancher’s pocket,” he said. “Outfitters as well are in direct competition with wolves, but we see it as a balance between tolerance and the impact of wolves being there.”

According to USFWS records, 76 cattle were killed by wolves during the program, and compensation was paid.

But Wehrheim says the county commission’s research puts the number of cattle killed at 1,500 because “what happens is a pack of wolves move onto a ranch where livestock are easy meals and stay there until they put that rancher out of business.”

Opponents of the program, organized under Americans for the Preservation of Western Environment, predict that once the wolf pack reaches 200, they will kill more than 7,000 game animals and head of livestock in a five-year period, costing the county $60 million in lost revenues from ranching and hunting.

“They’re putting wildlife in front of everything and, frankly, we are losing the battle,” Wehrheim said. “They’re like a cult, they worship the wolf and say the wolf is almighty. It is really ridiculous.”

Wildlife managers counter that sincere efforts are made to communicate with ranchers regarding locations of wolves. Collared wolves are tracked by air and ground, and locations are updated weekly on the Arizona Game and Fish web site.

It is illegal to kill or harass an endangered wolf on private or public land unless it is threatening a human life, considered by experts to be extremely unlikely. Managers utilize Range Riders on horses to guard livestock and run off wolves.

Hunting not affected

The number of tags issued for elk and deer season has not been affected by the wolf program, according to Chris Bagnoli, a habitat specialist with the USFWS.

With wolves in the area, elk are more wary, do not hang out in open meadows as much and therefore give riparian plants, such as willows, a chance to rejuvenate.

“The fact that we have not seen a decrease in hunting to me indicates that there is a healthy, functioning ecosystem here that provides the forage, prey and cover for sustaining deer and elk populations, livestock, and wolves as well,” Bagnoli said.

It seems poetic justice that wolves again wander the nearby Aldo Leopold Wilderness, named for the famous naturalist whose life was profoundly changed when working as triggerhappy government bounty man hired to kill wolves.

“We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes . . . and I realized then that there was something new to me in those eyes,” Leopold wrote. “Perhaps this is the hidden meaning in the howl of the wolf, long known among mountains, but seldom perceived among men.”