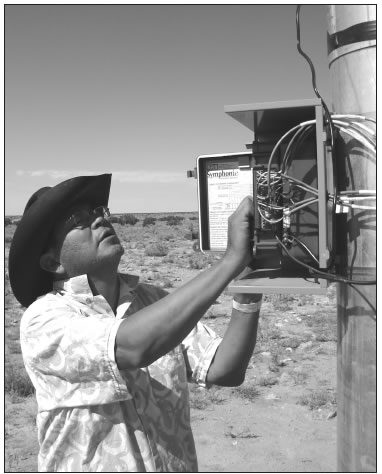

Ed Singer, newly elected president of the Cameron (Ariz.) Chapter of the Navajo Nation, examines data from a wind anemometer. Photo by Sonja Horoshko

The winds that swirl around Gray Mountain in northern Arizona have generated a cyclone of controversy, a power struggle over who will reap the benefits of their energy-producing potential: the Navajo Nation’s central government, or the tiny community of Gray Mountain-Cameron, Ariz.

“For years we have had no room to develop anything or improve our lifestyles,” said Ed Singer, newly elected president of the Cameron Chapter of the Navajo Nation. “Now, it is our turn to take responsibility and profit from it.”

But the chapter is up against a powerful competitor: a corporation started by one of the Kennedys and backed by the tribe’s central government.

At stake is control of a 250-megawatt wind farm, first on the Navajo Nation, that is designed to take advantage of the enormous renewable-energy potential on the sprawling, 26,000- square-mile reservation.

When Singer talks about the dynamic energy in the Gray Mountain- Cameron community — which lies some 60 miles south of Grand Canyon National Park on State Highway 89 — he likes to read from “Arctic Dreams” by Barry Lopez:

“The mingling …[in] border zones … Flying creatures… walk on ice. They break the pane of water with their dive to feed. Marine mammals break the pane of water coming the other way to breathe…in biology these transitional areas between two different communities are called ecotones.”

Singer believes his own community is like an ecotone.

“It’s how we have always been because we are settled in the center between Flagstaff and the University of Northern Arizona, the Grand Canyon and tourist industry and Tuba City,” he said. “We’ve had a lot of practice going back and forth across the three border zones, and we do adapt.”

Two years ago Bruce McAlvain, vice president for corporate development for International Piping Products (IPP) of Texas, arrived at the Cameron Chapter House. He brought with him ideas and plans he hoped to present to the Gray Mountain-Cameron community.

Singer was already aware of the growing interest in the wind on Gray Mountain and the possibility that it could generate electrical power.

“I told him it was the best idea I had heard, the most appropriate use of the land and resources,” he said. “Within two months we had him on the agenda with a resolution to do a wind study.”

After considering the land use and impact issues, the spirituality of wind and the effect collecting it would have on the community, the chapter called for a vote, seeing the project as something the community could support because it could participate in decisions affecting its own well-being and the profits promised some relief for the region’s struggling economy.

The chapter approved it as a Community-Based Initiative under a Navajo Nation regulation giving communities the legal and proprietary right to do business in and for the benefit of their own community.

A 34-year standstill

IPP’s interest in the wind industry began six years ago, McAlvain said, “when we started supplying high-quality- grade steel for the turbine industry. Then we got into other components like yaw bearings, which are what allow the cell to rotate, turn into the wind.”

It was a natural progression from supplying materials to manufacturing to the development side of wind-farming. Because McAlvain is part Choctaw, he began looking at projects on Native American tribal land. It brought him into contact with Bill McCabe, a petroleum engineer at Stanford University who has been a consultant on tribal energy projects for over 10 years.

According to McAlvain, “Bill gave me statistics that show tribes should be receiving roughly $30 billion annually from energy revenues. They currently receive $1 billion.”

IPP looked at four possible projects but selected Gray Mountain as the most promising renewable-energy site. When the community chose McAlvain and IPP, the company set up a not-forprofit named Independent Power Projects.

Its mission provides a working template for other tribal energy projects, educating the community for the time when it would assume the responsibilities of shareholders and decision-makers. It includes a board of directors appointed from the Gray Mountain- Cameron area.

McAlvain and IPP were granted a conditional-use permit from the central government in Window Rock to begin a feasibility study.

Around the same time, a major hurdle fell away with the removal of the Bennett Freeze — a 34-year moratorium on construction and development around the Cameron-Gray Mountain area. The ban had been imposed in 1974 on 1.5 million acres of Navajo- Hopi land by former U.S. Commissioner for Indian Affairs Bob Bennett, while old land disputes between the Navajos and Hopis were hashed out.

The ban forbade any new construction or even repairs to existing buildings, which stopped nearly all economic development in the area. No schools, no new business buildings, no additions on homes.

During those standstill years, however, five transmission lines were built across the Gray Mountain-Cameron area, claiming land for easements for the lines.

The transmission lines were controversial.

“No one in our community knows who delegated the authority to seize the land by eminent domain,” Singer said. “We have asked central government many times and never get an answer. In addition to the effects of the Bennett Freeze we also lost 150 feet from the center of the transmission lines out. When you multiply that by hundreds of linear miles it represents thousands of square miles and a great loss to the future economy.”

The lines are owned by power companies and consortiums such as Arizona Public Service, Western Area Power Administration (WAPA), and El Dorado Energy, owned by Sempra Generation, which sells electricity to the wholesale power markets of Nevada, California and the southwestern United States.

Two coal plants in the Four Corners region already use the transmission lines and a third, the controversial Desert Rock, to be located at Burnham, N.M., is in the planning stages.

Green lights ahead

But the lines may prove a boon to the wind project.

As part of its agreement with the Cameron Chapter of the Navajo Nation to provide community benefits in return for the opportunity to conduct a wind-feasibility study, International Piping Products did improvements such as de-silting this stock pond, which sits under two of the five transmission lines that cross the Gray Mountain area. Photo by Sonja Horoshko

The cost of transmission lines is a significant factor in any power project but particularly relevant to the economic feasibility of the Gray Mountain Wind Farm. Because the lines are already in place, “we — the community of Gray Mountain — are in the queue, at the head of the line,” Singer said.

“In addition,” added McAlvain, “The Moenkopi ISO station is in place.” Electricity is routed through that point two miles south of Cameron to 30 million Californians via a long-distance, high-voltage transmission system that delivers wholesale electricity to local utilities for distribution.

Also helping out the wind farm is a federal tax credit for companies that generate wind, geothermal, and ‘closed-loop’ bioenergy.

And California is requiring 33 percent of its electricity come from renewable sources, McAlvain noted.

McAlvain began the feasibility study with the full backing of the community. They assembled a Navajo crew, training them to construct the anemometers on Gray Mountain to measure the velocity, direction, volume and consistency of the available wind.

IPP got its conditional-use permit in August 2007 and the first anemometer, a 50-meter, went up in October. It measured and collected data for a year, said Singer, a member of the anemometer construction crew. “In the subsequent summer [2008] we put up five more 60-meter towers.” IPP also would like to put up five more anemometers to “fine-tune” the best spot for the turbines.

During the construction phase, negotiations between Sempra Energy of San Diego, Calif., and IPP began. IPP’s proposal to do the initial feasibility stage included researching the best fit for an energy company to join the development team after the feasibility study was completed.

The people of the Cameron Chapter approved Sempra Generation as the company of their choice. Sempra began holding community workshops to answer questions and build a coalition anticipating the time when the changeover would take place from IPP as lead developer to Sempra. The project seemed to have nothing but green lights ahead.

A surprise development

But in spring 2008 the situation suddenly became more complex. Word began to circulate that Navajo Nation President Joe Shirley and the Diné Power Authority (an enterprise of the Navajo Nation) had signed an agreement with Citizens Energy Corp. in Massachusetts to construct a wind farm on Gray Mountain.

The Arizona Republicreported on March 28 that, “Hundreds of windmills reaching nearly 400 feet into the sky could begin sprouting on the Navajo Reservation north of Flagstaff under a new agreement to harness wind energy for electrical use.”

The article said that the Navajo Nation had announced that it would partner with a Boston-based company called Citizens Energy Corp. to build the Diné Wind Project, the first commercial wind farm in the state.

“The enterprise was sealed this month by Navajo Nation President Joe Shirley Jr., other key tribal officials and Citizens Energy Chairman Joseph P. Kennedy II, a former U.S. congressman and son of the late U.S. Sen. Robert Kennedy and Ethel Kennedy,” the Arizona Republicsaid. Kennedy started Citizens Energy about 30 years ago as a nonprofit to provide low-cost heating oil to families. According to Citizens’ web site, “Citizens Energy is heavily involved in the wind energy industry through its for-profit division, Citizens Wind.”

Back in Gray Mountain, Singer had just finished reading “Cape Wind: Money, Celebrity, Class, Politics, and the Battle for Our Energy Future on Nantucket Sound,” by Wendy Williams and Robert Whitcomb. The book describes the controversy over a proposed wind farm in Nantucket Sound; much of the opposition is from the monied people who own beachfront property there, including the Kennedys.

Until the news began to break about Citizens Energy, the people of Cameron-Gray Mountain had never seen any company officials in their community. They were surprised about the agreement among Citizens, the tribal government, and Diné Power Authority.

The Diné Power Authority, said McAlvain, “is supposed to remain neutral. How can they represent the people when they have an agreement with Citizens and give them preferential treatment?”

The community with the transmission lines crossing it, which had been strangled by the Bennettt Freeze until 2006, had not been asked to partner in a project that would construct hundreds of wind turbines on its land with no direct benefit guaranteed to the people living around them.

The Kennedy charisma

In April, Joseph Kennedy Jr. flew to Window Rock to speak to the Navajo Tribal Council. On April 24, 2008, the Gallup Independent reported, “The trademark Kennedy charisma and impassioned speech brought the Navajo Nation Council to its feet as the eldest son of the late Sen. Robert F. Kennedy spoke of the poverty of Indian nations and prejudice in Congress against Native Americans.”

According to the Independent, Kennedy reminded the council that “human beings aren’t all-powerful, that we don’t have some God-given right to just dig up and develop anything and everything that we see to the detriment of local communities as long as some people can get rich.”

The newspaper story continued, “…Navajo Nation President Joe Shirley Jr. announced Monday during his State of the Nation address that the Nation entered into an agreement in principle with Citizens on March 12 to explore wind energy development.”

Gray Mountain-Cameron residents wondered why the Navajo Nation had entered into an agreement in principle without their input.

The story said the venture is expected to create up to 150 temporary construction jobs and 10 to 20 permanent jobs, and provide about $3 million in annual tax and royalty revenues, with an option for the Navajo Nation to acquire majority ownership at some future date.

Kennedy was quoted as saying, “… one thing you’ve got is wind; and you’ve got sun … and with that we can make money.”

Nothing wrong with that, said Singer, except, “Isn’t this the same man who didn’t want his viewshed spoiled by a wind farm in the waters off the shore of Nantucket Sound where the Kennedy family compound is located? Without asking us, Citizens Energy contracts for his company with the central Navajo government to dig up our land and put a wind farm in our immediate backyard. He must think we don’t read and that we’ve never heard about Nantucket Sound.

“It’s OK with him to put what he does not want to look at from his beachfront property in our back desert yard. We all read the book [‘Cape Wind’]. We have heard the radio program where he likened Nantucket Sound to the great national parks. Do they really think we are going to let Citizens Energy up on our mountain?”

But Citizens Energy continues to insist it has business on Gray Mountain. “They are very aggressive about going on the mountain as if they have a right to walk on our property,” said Singer.

“They show up with flyers to hand out at the Western Navajo Nation Parade, which we know will just confuse the people and consequently the project. They show up at planning meetings with requests to get on the agenda for the next chapter meeting.”

At a recent meeting, McAlvain said that the Citizens representative told him and a representative of Sempra they are not backing off the project.

Even so, when Citizens officials asked the chapter to pass a resolution granting them development rights, the community responded with an emphatic “no!” At the same meeting a woman asked the Citizens representative, “What part of ‘no’ do you not understand?”

But the partnership between DPA and Citizens is in place. And Ted Bedonie, the outgoing chapter president, supports Citizens, even though the community he represents has selected IPP and McAlvain.

A place at the table

The first phase of the feasibility study found that the net capacity of the wind is 33 percent. The capacity factor is the actual energy produced over a given period of time divided by the energy that could be produced if the generator ran at full rated capacity during the same period of time. Most wind farms have a capacity of 30 to 40 percent.

The 33 percent figure could be enough to make the Gray Mountain farm profitable, especially considering that its infrastructure is already in place. In fact, McAlvain believes, “It is plausible that a 1,000-megawatt facility could be built there someday.”

But who will ultimately operate and benefit from the wind farm?

The matter is bogged down in legalities at the present and is being reviewed by the Navajo Nation’s attorney general, according to Singer.

Singer ran for president of the Cameron Chapter in November and won. He takes office in January. “Because a component of our local government was not supporting the resolution that the community passed to develop a wind farm with IPP, I ran for the office.

“I want the wind farm to come to fruition. I see it as the single biggest economic impact that can happen in our part of the country. I want to negotiate a better position because we have lived too long with the power lines, the Bennett Freeze and all the recreation activity around our community.”

The people of Gray Mountain- Cameron are suspicious of Kennedy’s energy company. They say this is the people’s land and they have not given Citizens Energy permission to be up on the mountain.

But one way or another, things look good for the future of renewable energy on the reservation.

McAlvain is optimistic. “Now that the local government has a new president I feel we will be able to capitalize on our momentum. The community embraces the project. The key to success is still the people in the community. If they want it, it’ll happen.”

Singer strongly believes in the wind farm. “We are turning to nature and natural cycles. I think the Native Americans have always been more in tune with that and I think from here on the Native American has to be at that table whenever renewable energy is discussed.”