When Samuel Holiday was forcibly enrolled in the Tuba City Boarding School as an 8-year-old, he was firmly told it was “English language only! – No Navajo!”

He tried to comply. He studied hard, but he wasn’t as good at English as he should have been and spent many Saturdays scrubbing the school floors and walls as punishment for resorting to his native language. Finally, he enlisted the help of fellow boys in the school who were better than he was at English and willing to teach him – for a hefty price.

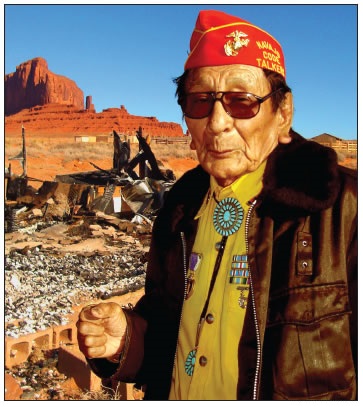

Samuel Holiday, 87, stands near the ruins of his house in Monument Valley on the Utah-Arizona border. Two young Navajo architects have teamed up to help build him a new, energy-efficient, rammed-earth home. Photo by Sonja Horoshko

“I emptied my pockets, gave them all my cookies and pieces of my cake and they taught me more English. I improved, but they were also bullies,” Holiday relates in a storytelling style. “A friend of mine, John Benally, was on the boxing team. He told me I should sign up. I did, and the bullies never bothered me again.”

Holiday continued his studies, becoming facile in English and boxing. Both skills contributed to the confidence he needed when he joined 280 other Navajo men recruited into the United States Marine Corps for combat duty in World War II. He served with distinction in Saipan, Tinian, Kwajalein Atoll and Iwo Jima as a Navajo code-talker, communicating with other Navajos, who were called the “walking secret code,” in planes, ships and battlefield throughout the Asian Pacific Campaign. They are credited with saving thousands of U.S. and Allied forces while helping to bring closure to the war.

When he signed up, Holiday says, “The Navajo and white recruiters told me they would help my mother, and, buy me a white man’s home with running water if I volunteered.

“I never got the house,” he adds. “Finally, I got my own home here in Monument Valley, where I was born.”

But the house he paid for himself, located just a mile west of the Monument Valley Visitors Center, within sight of visiting tourists, burned down last summer. In fact, it was the second time his home has burned, and the final blow after years of guarding his home against the vandalism and arson he suspects is responsible.

A good opportunity

Now 87, Holiday says he is getting help from two young Navajo men, not through the U.S. government or Navajo government agencies, but from the not-for-profit project they co-founded to design and build The Samuel Holiday Residence 15 miles south of Monument Valley at the base of a geological landmark known as El Capitán.

Merrill Yazzie is a recent graduate of the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of New Mexico. Chris Hansen, a high-school friend from Albuquerque, recently graduated from the University of Arizona College of Architecture.

Even though they played in a band and spent time hanging out together they didn’t know of their mutual interest in architecture. Looking at each other’s portfolios after college graduation they found “a lot of similarities in sustainable-design and alternative- construction interests,” according to Hansen, and a shared hope that some day their professional skills will help improve housing on the reservation.

They were eager to get to their careers, but not planning on pushing the cultural giveback timeline.

“Both of us were looking for work, and then we heard about Samuel Holiday’s situation. We decided that it was a good opportunity to make work we could do ourselves while we looked for work with architecture firms,” Yazzie says.

With the slump in the U.S. economy, prospects for employment in architectural design today are slim. Kermit Baker, American Institute of Architects chief economist, reported that, “employment at U.S architectural firms peaked during the summer of 2008, and exhibited steady declines the next two years. For the past 12-15 months, employment levels have been bouncing around this bottom rung…This prolonged downturn has meant that many architects downsized at the beginning of the economic crash have been waiting a very long time for recovery.”

Tough timing for entry-level architects. But rather than focusing on the bleak prospects in today’s design market, the young architects teamed up to design and build an affordable, efficient, sustainable, rammed earth home on the reservation for Holiday.

The model project propels a solution to substandard Navajo housing conditions away from bureaucratic processes and back into the hands of the people. It will, they hope, get noticed, and introduce Navajo people to alternative, do-it-yourself building techniques that use materials that are near at hand, familiar and akin to traditional Navajo building materials for the early hogans that were made of mud.

“We’re using alternative strategies to help keep construction costs low. Rammed-earth construction is typically cost-effective, labor- intensive yet energy-efficient,” Yazzie explains. “The walls act as a thermal mass, absorbing the heat from sunlight, releasing it slowly during the night. This helps keep it cool in the summer and warm in the winter.”

Declining hierarchy

Yazzie’s former professor at UNM, Kristina Yu, believes in the young architects’ design project.

“In the 1980s and ’90s, architecture was self-serving, hierarchical. Learning architecture was a singular activity,” she says. “Today there is a growing trend to dispel that approach in academia. Younger students coming into the profession want to be more relevant to culture, the planet, the humanity, responsive, like Yazzie and Hansen, to an overall palpable sense of the times. We are re-thinking what is ‘a good way,’ a newer ways of practicing architecture, seeking to understand projects from within.”

After they finished the design development Yazzie felt unsure about the structural integrity of the rammed-earth construction. He went to Yu with his concerns.

“When we talked over the insecurity about the materiality, I told him, ‘It’s just earth. If it fails it’s not the end, we’ll just build it again. No one goes into it until it stands up for a while.” She agreed with their plan to build a test wall before the project begins to determine the right mixtures of elements to reach 300 psi, the correct strength, without concrete. To do it they need a pneumatic tamper, and all the muscle they can get, says Yazzie.

“It’s amazing that Merrill saw the cultural asset in Samuel Holiday, a living legend; that maybe the project would be something colleagues could get involved with. It requires insight, courage and energy to take on a design decision like this with conviction and wear the management hat too, making all the complex come together,” Yu adds. “As an educator, it is exciting to see the practice expand to include ‘let’s see where my two cents’ worth of knowledge can fit.’”

Holiday is currently staying with his daughter, Helena Bengaii, in Kayenta, Ariz. She accompanies him on his many speaking engagements throughout the country and stores his memorabilia for him at her home.

“About two weeks after the incident,” says Bengaii, “they called and asked if they could get together to talk about a plan to build my father a home. They said it wouldn’t cost us anything.”

“Oh, yeah, right,” she thought, knowing her father had heard that before. “And then when we met with the two gentlemen I was very impressed. They are working hard to make the project work for my father, keep us posted on their progress every week.”

Form follows fancy

When Yazzie and Hansen finished drafting plans for the home, they showed Holiday. “He thought it was too fancy,” Bengaii remembers, “but then they explained the drawings and the simplicity became visible. They even included a detached separate display room for his memorabilia and awards. He is getting on in his years and they made it really simple enough for him.”

Indigenous Community Enterprises of Flagstaff, Ariz., has stepped up to offer their 501-c3 status as the flow-through for materials and funding contributions. Hazel James, spokesperson for ICE, says that the project is a perfect fit for their mission to help the elders maintain dignity.

“Most veterans have never been given the housing support they deserve, and the veterans housing is a four-to-five-year process. So we will do whatever we can in our capacity to connect them to other resources and partnerships.”

Holiday’s new home is posted on the website, samuelholidayresidence.org. Hansen designed and manages the internet component, which includes Facebook, while Yazzie networks the project to corporations and interested individuals willing to help.

The fully rendered two-bedroom home is bare-bones. Its functional simplicity is elegant.

Richard Tall Bear, president and CEO of Tall Bear Group, a Native-owned and -operated solar-energy design company based in San Diego, has been looking for a situation where he could donate a solar-energy system to a home project on the Navajo reservation. The straightforward, professional approach the two architects have taken appeals to Tall Bear.

“Nobody’s going to argue about Mr. Holiday receiving the system from my company. We respect his service and we’re going to make it very maintenance-free for him.”

Tall Bear Group designs residential and commercial-scale renewable-energy systems. He believes that tribes can generate power locally.

“It strengthens tribal sovereignty, but it starts at the home site. The biggest impact is felt by the family and then it grows from there.”

Yazzie and Hansen have sidestepped the red-tape of government housing procedures by launching the independent project on the Internet. Hansen designed the web site and manages it and the Facebook page where friends are directed to Holiday’s code-talker web site as well as the project web site pages.

There are two goals, Hansen writes. “The first is to construct a new home for Samuel Holiday. The second is to display and utilize alternative construction methods that will result in a comfortable and efficient home.”

“In fact,” says Yazzie, “Native Americans are so accustomed to a minimal construction style that we changed the original renderings to just present the form and function of the building because it simplifies the concept of rammed earth. As a Native American it is a natural fit to help on a project like this.”

The project is a breakaway model in process. It shows planning, direction, concrete materials and techniques, fluidity, timeliness, assurance and compassion while addressing a need to solve a housing crisis for an elderly. It’s a small project in a sea of large, complex remedies that can lose sight of an end goal. Yazzie and Hansen bring integrity to their solution by volunteering to do the work that they are asking others to help with.

The time-line is tight. In the fall they set up booths at the Shiprock, N.M., and Tuba City fairs where they displayed blueprints, passed out flyers and signed people up on an email list.

Enthusiasm is growing every day, Hansen says. “We hope to finish the house by National Codetalker’s Day, August 14th, 2012.”

Anyone wanting to register a vote of confidence, volunteer labor or contribute funds or materials is invited to learn about the project and contact Yazzie and Hansen on the Samuel Holiday Residence Facebook page.