Wheat-paste images surprise drivers on Navajo rez

It’s easy to miss highway wheatpaste street art while traveling 70 mph across the northern Navajo Nation, under the mesmerizing influence of the sensual land. The beauty swallows the presence of occasional vacant buildings covered in graffiti, empty billboards and bare interiors of cobbled- together arts and crafts kiosks. Life flows effortlessly on Highway 160 until something out of place flicks by like a deep-tone jewel at the side of the road, causing us to notice that something timeless, fixed, has changed.

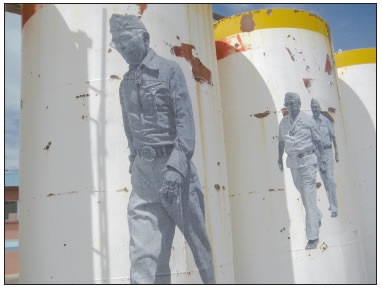

Images of code-talkers from a Navajo Mountain celebration are wheat-pasted on tanks near Cameron, Ariz. Photo courtesy of Jetsonorama

We stop, turn the vehicle around, back-track to the Cow Springs Trading Post pull-out, and park.

There, pasted on the roofless, abandoned, crumbling building under the barely legible signage stands a giant portrait of a traditional Navajo grandpa, Hank Nez, wheat-pasted over graffiti painted by an earlier generation of guerrilla artists. His wife, Thelma, twirls out over the enigmatic messages and rubble one vacant window away from his side.

It is a magnanimous silent message bearing no signature in the bottom corner, no ego attached. Anonymous.

The impact feels like love, like a surprise birthday gift; Christmas morning; child in wonderland. Who did this — for us — when we weren’t watching?

Guerrilla art

Street art — public art on concrete canvas, the unsanctioned, hip, political statement — is usually made in urban settings. By definition it is found where a lot of people travel on foot, bicycle, public transportation and skateboards. Political content, and social comment such as that found in the technical virtuosity at www.blublu.com, is intended to generate a subculture buzz. In that urban milieu it can, because artists are agents of change.

But so can it happen out here. Today the corrugated-metal siding on abandoned buildings, cinder-block laundromats and plywood bead stands on the rural rez serve as frontage for a street artist living in the Navajo Nation.

Even though much of his current work is sanctioned, “Jetson,” a Shonto, Ariz., man, prefers not to use his real name in order to protect his day job. Plus, it keeps his work “clean” — centered on the purpose, the liberties found in public art.

Jetson is bringing back a message of beauty that has been fading from public view. Now, elders, sheep, the rodeo bronc rider, Susie — clutching her Bible to her bosom while singing on the side of a vacant convent — an occasional horse and three code-talkers walk out from the surfaces of these places because of the gratitude Jetson feels for the Navajo people.

“Working on the Navajo Nation has proved to be one of the most difficult, yet rewarding experiences of my life,” he said. “I’m indebted to the Navajo people for the life lessons they’ve taught me.”

Jetson’s medium is wheat-paste, a style of guerrilla street art where the work is pasted to buildings or other surfaces. Prior to these projects he concentrated on photography, creating portfolios of Navajo culture and lifestyle that are culturally sensitive and produced with the permission of the people. He uses his own photographs for this current public art.

“The wheat-pasting is a way of putting myself out there a little. I’m really thankful for the opportunity to give something back in a different way than I have been engaged in over the past 22 years. I look forward to the dialogue it may return.”

‘Everybody’s grandma’

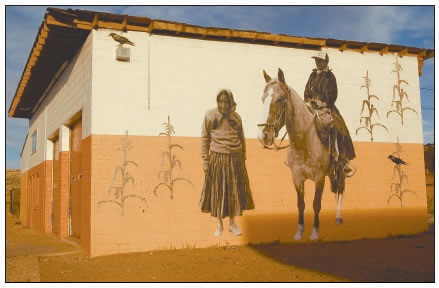

Jetson and a fellow anonymous artist collaborated on this public wheat paste project near the convenience store at Black Mesa Junction on Highway 16 west of Kayenta, Ariz. Photo courtesy of Jetsonorama

And the dialogue has already begun, with another anonymous artist adding to Jetson’s work put up on unsanctioned locations, such as a bead stand on Highway 89 near Tuba City, Ariz.

At first Jetson worked alone, when nobody was looking. But then one morning a black-and-white copy of a wolf appeared in the flock of sheep he had pasted on a plywood wall in the presence of the three code-talkers. “The wolf isn’t mine. I love it. . . that I started a dialogue with another artist who was inspired by my initial pasting.”

The two now occasionally collaborate under the moniker, “No Reservation Required Crew, NRRC.” In October they pasted an enormous wall at the Black Mesa junction convenience store. Corn stalks and ravens contributed by the other artist add a Navajo context, a spatial depth of field surrounding the 12-foot grandmother and 15-foot young man on a horse. When asked what he thought of the startling image appearing overnight, a Black Mesa customer said, “That’s everybody’s grandma on the reservation. She stands for all the grandmas of us Navajos,” and then he asked, “But how’d he do it?”

It is problematic anywhere to make copies 15 feet tall and 10 feet wide. Jetson uses a combination of digital technology, Kinko’s copy services and old-fashioned wheat paste made exclusively from Blue Bird flour, water and a little sugar. After tiling the high-resolution black-and-white photographs, he prints them in sections which are then cut out like paper dolls, matched, seamed and pasted back together on the wall.

He says that the process magnifies his feelings for the land and the people. Both are very alive and special, “and my sensitivity to wind and weather has increased. It will inhibit a pasting session because it’s so difficult to control the paper,” on a tall ladder, braced against a building at sunset while they put up 10-foot strips of paper beside the next 10-foot strip.

In urban settings, street artists work at night because the pasting is mostly done in unsanctioned locations. But Jetson takes the opportunity to work in daylight out on the rez. “The Navajos do not harass me and that includes the authorities. Instead, I am respected as an artist.”

‘A jolt of joy’

The majority of his work is pasted near the highway because it is a highly visible way to share on a large scale and “easier to remove my ego,” he says. “I don’t sign my pieces. There is no way to find out from the piece who I am. In that way it is not about me or for growth into the gallery scene.”

In fact, his public art is given freely to more intimate sites as well, in extremely rural locations, for the benefit of the people who actually live there. You will not see these sites unless you live nearby. But because Jetson is developing a following he now makes some of the projects available in stop-action films produced during the process and posted on YouTube.

Watching the No Reservations Required Crew on video is an opportunity to see the magic in art.

There he is, Jetson in Bitter Springs, balanced on his side, dangling over the tall, tall chimney of an empty home in a blazing orange canyon at sunset. Time passes with no audience or patron; no outside funding for his art, no gallery percentage or marketing budget as he pastes up his friend, the giant grandpa, Hank Nez, to stand tall, inhabit the house, and remind us that people like Hank and Thelma lived here once upon a time, somewhere near Navajo Mountain.

French street artist JR says in a video documentary of his current wheat-paste project in Paris, “The pictures may disappear over time, but the images will stay in people’s minds. It changes the way we used to see the places and the walls on which the images are glued.” JR is right; wind, rain and time may obliterate the paper, paste and ink, but the desire to look upon these silent people bearing messages of dignity and harmony is renewed.

“The real deal is happening out on the rez, where it’s all about context,” Jetson said. “Driving across the desolate and somewhat impoverished landscape is overwhelming in a soothing way, but then to suddenly have art appear is, I hope, a jolt of joy to the system.”

Jetson’s work may be found on an Internet search for “Jetsonorama.” His YouTube videos are titled: “black mesa junction 10 10 09”, “bitter springs 10 11 09”, “gray mountain 10 12 09 (new + improved).”