Keith Hutcheson is a contented artist today. His retrospective painting exhibit at the Anasazi Heritage Center is an opportunity to survey decades of his own visual art work hanging as a portfolio in its entirety for the first time. He sees the diligence, but not the effort and is surprised by the amount — 60 large oil paintings done over 30 years while living in the Four Corners region.

“It’s satisfying,” he says.

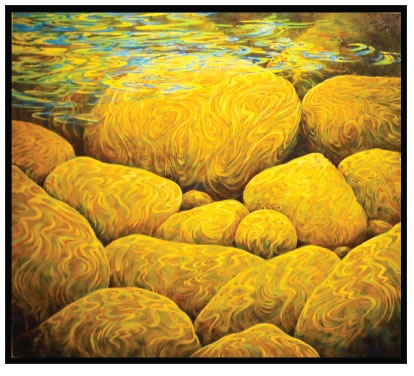

Untitled, 2009, is an oil on canvas that is on display at the Anasazi Heritage Center as part of the Keith Hutcheson Retrospective 1973 – 2011. The show continues through March 18. Admission to the Heritage Center will be free through the end of February.

When Michael Williams, exhibit specialist for the Anasazi Heritage Center, proposed the show, Hutcheson wondered if he had enough work to fill the large, open space. Although it had been stacking up in an extra bedroom in his home and had accumulated in friends’ collections over time, he was surprised by the deep introspective volume of subject matter, the consistent number of large canvases.

“It really struck me to hear so many of the guests at the opening say exactly what I was feeling: ‘I had no idea you had painted this much!’”

The special-exhibits hall is the best opportunity in the region to offer an unobstructed and focused view of any public presentation. True to the professionalism of the Anasazi Heritage Center, the Hutcheson Retrospective is an example of discriminating planning and intent. Each piece is hung thoughtfully in museum-style welcoming the viewer through the space easily, engaging mind and heart with Hutcheson’s bold color and large familiar view of his subject matter — the Southwest’s rivers, canyons, mesas, forests, clouds and rocks.

As an avid, often solitary, fly fisherman and hiker, he has seen all that the viewer sees in the paintings. He’s been there, and brought his feelings home, putting them quietly on the canvases in his studio.

It’s the “deliciousness of the painted surface” that he likes, the business of being alive, how to capture the flesh of the natural world.

The Heritage Center is a top-flight museum. Enticing as Hurcheson’s rivers and rocks may be, don’t touch the paintings!

But Hutcheson does. Walking up to one of his river works in the exhibit he reaches out to it. “The painting becomes the teacher,” he says, while touching the surface of one of the three large river rocks in “Untitled,” 2006. It is a poignant gesture, suggesting that he cannot resist the painting’s call to take him back in time to a place where he actually felt the rocks beneath the surface of the water through his waders, bent down into the river to take up a fly on the end of a line stuck there in the shallows near the bank.

We, too, the observers, know or sense we’ve been there with him, going with the flow of his subject matter. It’s a compliment to the viewer, close to the bone of our own experience, that by his modest approach he lets us in, lets us tag along with him through the painting to the place it represents.

“It’s easy to be present in the land and water. We’re fully there in the natural world,” he says, assuming we have been there because he has been there.

But how does he paint flowing water if he’s standing in the middle of the river? Where’s the canvas?

“You can’t hold a paint brush and a fly rod at the same time,” he says. “It’s impossible to set up a canvas and work in that circumstance while you’re fishing.” Instead, back in the studio, Hutcheson paints a series of powerful hints for us about where we are standing with him.

The oil painting “Untitled,” 2009, is a case in point of painted suggestion. A transparent plane on the surface of the water — tough enough as a subject — that begins in the upper left corner, floats out in a few canvas inches toward the viewer, and trails away. From that point on Hutcheson gives us more information by painting the shadows of the ripples instead, that fall over and around the rocks in the water at the river bottom. The method implies that the water is flowing toward us, that we are standing in it. He does not need to paint the water, but only the intimation of its presence around us.

The approach is complex, a visual puzzle. But his personal experience in the water gives him the power to wield the details in loaded brush strokes that help us complete the surface of the water in motion in our mind, the direction he sets for us by showing us the consequence of the sun-drenched moment on the river.

That is all he shows us. We fill in the blanks.

Although he never paints from photographs, he does use them as a reference to construct the painting in his studio. In doing so, he diverges from today’s marketdriven technique where many artists enlarge landscape photographs printed in giclée format on stretched canvas and then paint over the image. It renders something that seems masterful on first view, but is actually not more painterly than a contemporary, dimestore, paint-by-number kit. To a novice eye it is a barely discernible trick.

But to that same viewer, Hutcheson’s adherence to painting for the sake of the painting, the process and subject matter, it is an opportunity to be truly brave with the painter. To look instead of assume. Hutcheson’s work is generous. He’s willing to show his vulnerability.

“You can learn how to live by living,” he says, “and in doing so you sense the wonder of life. It’s challenging to make a painting, but it’s okay because the creative process is its own reward.”

For 29 years Hutcheson taught art in Montezuma-Cortez High School. He is highly respected by his students for the dignity he brought to the process of making art and the encouragement he provided to the novice art audience.

“I used to teach that there is nothing mystical or profound about it. It is just that you do something on the big white empty canvas and then you do something else until it feels right.” He could be talking about solving a routine plumbing problem or describing a moment with Click and Clack, the Car Guys, under the hood of a Jeep.

That is the magic in his work. It is facing you directly with all he has to offer the viewer. The integrity of the painting, painter and viewer is intact, in balance.

“Ten years ago I used to think a lot about the growing demand for entertainment in art, how it was changing painting into a personality culture. Then I gave all that up. The paintings I make are not about me. These paintings are alive. When I held up my 6-month-old grandson and walked him in front of the work, his eyes locked on the paintings and you could watch him marvel at what he was seeing.”

Hutcheson is not a naïve painter. His mastery improves with each new work while staying focused on offering viewers something they wish they had done themselves.

That is the inspiring element in his work. His humble personality throws open the door of collective experience relating common grounds to high art by exposing the dubious assumption that painting, or “Art,” is motivated by extraordinary feats of fame, intellectual vigor and entitlement, or technical accomplishment.

“I do it,” he says simply, “because I am always caught in jaw-dropping wonder at what I see and feel when I’m hiking or flyfishing. Everybody projects their own impressions on your paintings. The painter has no control over people’s responses. It is rewarding enough to just share this experience with a retrospective exhibition like this.”