The recently published memoir by Bessie White held me captive from cover to cover. Bessie’s Sylvan catalogues the life (so far) of the 89-year-old dry-land farmer, starting with her move to Montezuma County from Canada when she was a somewhat bratty 3 years old, through the not-so-Great Depression, the nitty-gritty Dust Bowl years, the second War to End All Wars and, as they say, much, much more.

The recently published memoir by Bessie White held me captive from cover to cover. Bessie’s Sylvan catalogues the life (so far) of the 89-year-old dry-land farmer, starting with her move to Montezuma County from Canada when she was a somewhat bratty 3 years old, through the not-so-Great Depression, the nitty-gritty Dust Bowl years, the second War to End All Wars and, as they say, much, much more.

But most of all it’s a tale of joyful survival, her family’s stubborn persistence in establishing a permanent presence on the land they came to love.

Co-authored by John Wolf, also a resident of Montezuma County, White’s tale makes an initial point of letting readers know she doesn’t think her personal journey is all that remarkable, although many may disagree. Her larger concern is making a lasting record of a truly loving way of living – on and off of that land, which, she laments, is fading from public memory:

“I felt like I wanted to put my life down,” she explains in the introduction. “Not that it’s more important – it’s not more important . . . probably as ordinary as anybody’s life.

“But it’s not there anymore for my kids and grandkids. They don’t live in that kind of world anymore.”

More’s the pity.

She is the last resident of Sylvan, Wolf notes, “one of dozens of . . . small communities that once dotted the Great Sage Plain. They’re all gone now, the post offices, the general stores, the schools and Grange halls. Plowed under along with the homesteads of most the families who settled here (and) replaced by irrigated operations ten times the size of the original farms.” (Still, a tidy cemetery endures there, and White is secretary of the board that keeps it.)

It’s the personal recollections, such as knowing your cows by name, getting down off your tractor to wage the yearly battle with bindweed, using a primitive party-line telephone system as a 911 signal — “. . . when they put out five rings, then everybody would pick up the phone and they’d give a message” – reliving talent nights and dances at those longgone schools and churches, and myriad other nostalgic recollections that makes this book so readable.

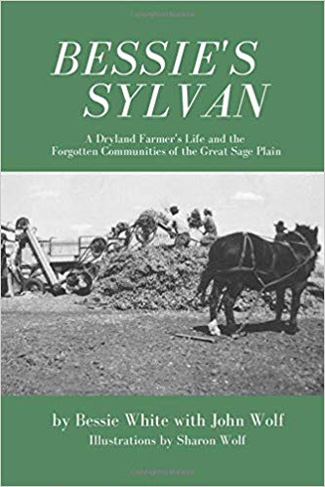

Beyond that, it contains a wealth of information and keen insights into the geology of the Great Sage Plain, the economic realities of dryland farming and the impact of the Dolores Water Project, last of the giant dams built to tame the wild waters of the West.It is replete with photos, maps and finely drawn illustrations.

The history of the West has been exaggerated and exploited by the entertainment industry to the point that much of what’s left it is impure fiction. Stretching over the years that cover a large part of what is now forlornly referred to as the time of the American Dream, Bessie’s Sylvan does its part in setting some of that straight.

On a personal note, I found a lot of relatable stuff in it that jogged my own memories. Hey, my family also moved into a house sans running water or electricity; wow, I grew up in a tiny village with a general store, went to a one-room schoolhouse, too; yeah, my dad had an old truck like that, and so on.

Whatever, Bessie’s Sylvan is a keeper, crammed with amusing anecdotes as well as a modest helping of unapologetic homespun philosophy that comes from living what Albert Camus called an “authentic” life.

Ms. White just closed her annual stall at the Cortez Farmers Market – “well, now all I take is 15, 18 pies, five or six loaves of yeast or whole wheat bread (along with cookies, jams and other goodies)” – but no doubt she’ll be back next year.

In the meantime, pick up a copy of her book if you’re interested in the history of our area. It’s good reading.