One of the things that has nurtured hope in my drought and pandemic-battered soul is the sight of dryland beans growing taller and bushier through the summer. Certainly, the monsoon rains helped them along, but they came up long before the rains and continued to grow long after. Surrounded by brown alfalfa fields (irrigation water was cut off in this part of the Dolores Project in early July), the bean fields were a contrast of vibrant green.

Who would have expected that this would be the year that dryland beans would out-produce irrigated beans? Actually, there weren’t many irrigated beans because there wasn’t enough irrigation water to support planting a full crop. Similarly, the field with the new center pivot irrigation system has turned into a big pigweed patch because there wasn’t enough irrigation water to seed alfalfa this year. Perhaps they should consider planting amaranth instead of alfalfa? Pigweed is a species of amaranth and as any local gardener will attest, it thrives in all growing conditions.

Another unexpected harvest was in the mountains, where we found the earliest and best wild mushroom flush in the past 5 or 6 years. Some say the solution to our current water crisis is more storage. But with the bountiful harvest of dryland beans and wild mushrooms, I suggest that we consider another option… more resilience.

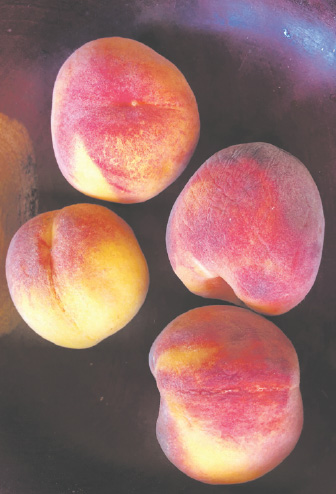

Peaches produced during this year’s drought.

To build more resilience into our food systems, I propose that we review our seed stock and growing methods to better match our available water and timing. Perhaps, we could return to intentional dryland farming that has successfully supported communities in our area for thousands of years. As a seed saver, I am always looking to grow new and exotic varieties in our red dirt to see what they produce under our unique high-altitude and water-limited conditions.

This year, I will save seeds from every fruit that I harvest, especially the “volunteers” that grew out of the compost. These seeds will become the foundation of my dryland seed bank. I also plan to swap seeds with my neighbors and make sure I squirrel away some Cahone bean seeds that were bred specifically to thrive in my garden’s micro-climate conditions. Resilience is in its genes.

Is it possible that we carry this genetic resilience as well? You don’t have to go very far back in your family tree to find ancestors that survived and even thrived through pandemic, war rations, and weather extremes – both drought and floods. We come from tough stock. You can look to your grandmother for the clues to your resilience. All your mother’s eggs (including the one that became you) were formed when she was a fetus growing in your grandmother’s womb. Therefore, your breeding for resilience includes your grandmother’s response to conditions during her pregnancy with your mother, such as availability of food and exposure to disease.

The bigger question is how to access this built-in resilience when we need it most. I think the answer lies in sizing and timing our expectations for growth and harvest to the available resources. For example, some folks I know tried an experiment this year comparing yields from dryland and irrigated gardens. Usually, you would expect lower yields from the dryland garden.

Resilient bean plant bearing Cahone beans.

But with irrigation being cut off in July, the dryland garden produced more than the partially irrigated garden. It seems that timing of flowering and fruiting in the dryland garden was better matched to the available water. In anticipation of limited water this year, my husband and I removed most of the blossoms on the trees to reduce potential drought stress on our young orchard. As a result, we had a much smaller fruit harvest, but the trees (fingers crossed) are healthy and vital. Also, we are enjoying some of the sweetest peaches we have ever eaten. Possibly, it is because there are so few peaches, and we are savoring each one. But it is also possible that the lack of water super-sweetened this year’s crop. The Hopi treasure their dryland peach trees for some important reason.

Another source for learning resilience would be to tap the oldest form of TEK (Traditional Ecological Knowledge). We are lucky in the Four Corners to be surrounded by indigenous farmers that hold knowledge from centuries of experience growing food in our corner of the world. We could ask and listen for their advice and guidance on how to thrive in drought.

Personally, I am curious about how to water my fruit trees for the sweetest peaches. With our extended growing season (I am writing this after the fall equinox and there has not been a frost yet), should be we planting with the monsoon? I certainly employ season-extenders in my garden, it’s time to learn about water-extenders. My new definition of a “bountiful harvest” includes the amount of water I use to grow fruit and vegetables. A true resilient harvest uses the least amount of water to grow sweet peaches and not one drop more.

Carolyn Dunmire is an award-winning writer in Cahone, Colo.