It’s not so hard to see why people in the late 1800s liked tamarisk trees. Their long, wispy branches boast showy pink or white flowers for much of the year. They can quickly grow to heights approaching 20 feet, and they make great windbreaks. Their combination of deep roots – up to 90 feet in some cases – and extensively branched surface roots naturally help stabilize soils along riverbanks.

And so they were planted, in yards and along western waterways throughout the early West. They took off.

Also called salt cedar, the tenacious trees jack up the salt in the surrounding soil by drawing up alkaline water and then depositing it around them as they drop leaves. The tamarisk can tolerate the saltier environs, but native trees – like cottonwoods and willows – cannot.

Also called salt cedar, the tenacious trees jack up the salt in the surrounding soil by drawing up alkaline water and then depositing it around them as they drop leaves. The tamarisk can tolerate the saltier environs, but native trees – like cottonwoods and willows – cannot.

Tamarisk trees now dominate 1.6 million acres of riparian, or riverside, habitat throughout the Southwest. They’re thirsty trees, and they spread wildfire more readily than native varieties, putting their ecosystems at greater risk than before. No major rivers in the Four Corners states have been spared the tamarisk invasion – not the Dolores, the San Juan, the Colorado, the Virgin, the Rio Grande or the Green.

Since about the 1940s, biologists have tried to remove tamarisk. In places such as Grand Canyon National Park, these efforts are often aggressive and even heroic, involving week-long treks or river trips into remote and difficult riverside habitats where the trees’ millions upon millions of seeds have taken root.

The biologists win battles – in pristine side canyons in Grand Canyon, for example, where they are able to stop the tree’s menacing creep. But until recently, the trees looked most likely to win the war. At the Grand Canyon, the trees are so well established along the Colorado River that park managers gave up trying to stop them there.

“From the beginning we knew we were not getting rid of the source,” said Lori Makarick, Grand Canyon’s vegetation program manager.

And then came the salt-cedar leaf beetle. This relatively new tool in the arsenal against the tamarisk trees, imported over the past decade and released into tamarisk thickets, is proving highly successful – more successful, even, than the USDA and its cooperating agencies expected. It’s been so successful, in fact, that some biologists worry the beetle could become a scourge in its own right, wiping out tamarisk trees too quickly for other species in the ecosystem to adapt.

Taking hold

Following two decades of research into the idea, the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) began importing salt-cedar leaf beetles in the late 1990s from Kazakhstan, China and other areas where they naturally munch on tamarisk trees.

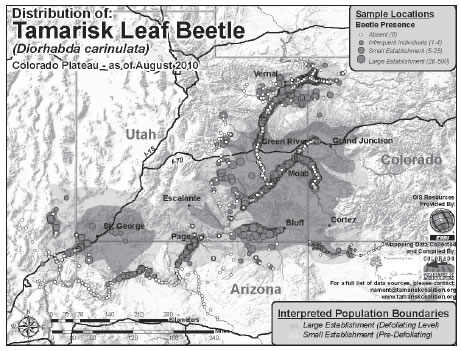

Starting in 2001, land managers in all the southwestern states – except Arizona and New Mexico — began releasing them into tamarisk thickets. Some of the first locales included Lovelock and Schurz, Nev.; Delta, Utah; Pueblo, Colo., and Lovell, Wyo.

In 2004, APHIS invited Utah agencies and organizations to collect beetles from the Delta location and release them in various private and state lands across the state. Many of those beetles went to Moab and St. George.

Jack Deloach, an entomologist recently retired from the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service, was one of the pioneers of the beetle introductions and once called the program “one of the most successful biological control projects ever in the U.S.”

He says the beetles have taken off from almost all the sites where they started. “In several places they’ve gone more than 200 miles from the release sites,” he said. “In Nevada, they’re all over the state now.”

The secondary releases around Moab have proved especially fruitful. They’ve traveled down the Dolores, crossed into northern Arizona along the Colorado and into New Mexico along the San Juan.

“It’s about 1600 river miles now that have been defoliated by that one release at Moab,” said Deloach.

Defying the odds

Salt-cedar leaf beetles, released in parts of the West to combat tamarisk, are spreading faster and farther than researchers anticipated.

Based on input from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, no beetles were released within 200 miles of nesting locations for the southwestern willow flycatcher, a bird endangered since 1995 that now appears to rely on tamarisk trees, nesting in them even when native trees are still around.

And there was supposed to be another built-in beetle-control strategy: the species released into Nevada, California and Utah wasn’t supposed to be able to survive below the 38th parallel, which crosses roughly above the bottom third of Colorado and Utah. They were adapted to more northern latitudes, with body clocks set to overwinter when the days got short enough. But farther south, such rhythms should have meant they’d go dormant way too soon, and never make it through consequently long winters.

But the beetles quickly adapted, staying active long past their normal bedtime, figuratively speaking.

In the spring of 2009, the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity filed a lawsuit against APHIS and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service over the “indiscriminate introduction of the tamarisk leaf-eating beetle into critical habitat of the endangered southwestern willow flycatcher,” especially because the group believed beetle introductions at St. George, Utah, were too close to flycatcher habitat along the Virgin River. The center settled that lawsuit just a few months later, when the agencies agreed to renew consultations on the beetle introductions in light of hazards to the endangered birds.

APHIS has since stopped introducing new beetles, but the agency has balked at the suggestion that it should help maintain the birds’ habitat by participating in restoration efforts to plant native trees, like willows, in the wake of tamarisk trees that may die from beetle attacks.

“With no evidence that anything is being done to remove jeopardy from the flycatcher, and with the beetle now poised to move below Lake Mead and into the Rio Grande Valley,” the center requested documentation of the agency discussions on April 14, in line with a plan to renew its lawsuit, Robin Silver, the center’s co-founder, wrote in an e-mail.

Meanwhile, in late 2009, Grand Canyon biologists got a surprise when they found just a few beetles about 12 miles downstream from Lees Ferry, Ariz.

Surveys last year revealed that those beetles — probably from Moab — are now eating tamarisk leaves between Lees Ferry, where Grand Canyon National Park begins, and Redwall Cavern, about 33 miles downstream. Another population of beetles apparently has migrated into the canyon from St. George, and set up shop 100 or so miles downstream.

“I am a little freaked out about how fast they’re coming and moving,” Makarick said. “We didn’t even expect them to be here.”

Management at national parks closely adheres to the National Park Service mission to “conserve the scenery … and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” Normally, that means parks will go out of their way to oust nonnative species so the native ones can thrive –removing tamarisk trees, for example, so cottonoods and willows stand a chance.

But Grand Canyon and other parks generally below the 38th parallel are in a bind with tamarisk, because the endangered, songbird-sized southwestern willow flycatcher has seemingly come to rely on the non-native tree.

So whereas Dinosaur National Monument in far northwestern Colorado can celebrate the fact that 50,000 tamarisk-eating beetles have begun to devour the leaves off the trees in much of that park, Grand Canyon biologists are worried.

The fear is that if the beetles kill tamarisks too fast, it will be a hit to wildlife species that have gotten used to them, especially the endangered flycatchers. Furthermore, without native trees to fill in the gaps left by dead tamarisk, other weedy invasives, like Russian knapweed, Russian thistle, pepperweed, and camelthorn, could take up occupancy.

Makarick says her team is about a year out from being fully prepared to plant native trees in the wake of tamarisk, which could die out after just a few seasons of beetle feeding. But they’ve already started collecting and growing native saplings – which, mercifully, grow quickly.

New food on the block?

Rusty Lloyd, program director for the Grand Junction, Colo.-based Tamarisk Coalition, a non-profit that aims to stem the tide of tamarisk invasion, says there are cases in Utah, Arizona, and Nevada where the beetles have defoliated tamarisk trees quickly enough to kill reptiles and insects by altering the microclimates they need to survive. The loss of tamarisk leaves has also fatally exposed flycatcher chicks to increased heat and predation.

But the beetles are inconsistent, and their patchy habits could give Grand Canyon biologists — and willow flycatchers — a break.

“In some tamarisk stands mortality has been very high, maybe 70 percent or more. In other stands, tamarisk mortality has been near zero,” said Kevin Hultine, a plant ecologist at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff.

And in some places, the ecosystem is showing signs it can rise to the challenge of beetle invasion.

Defoliation in northern Nevada slowed down when local predators keyed into the presence of the beetles. Arthropods such as ladybird beetles, assassin bugs, stink bugs, preying mantis, spiders, and ants tended to keep beetle numbers down, said Tom Dudley, a riparian ecologist at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

“Birds also fed readily on the beetles, and we saw increases in the diversity and abundance of birds in areas with beetles compared with nearby areas where they had not yet colonized,” he added.

Wing and a prayer

Deloach calls the southwestern willow flycatchers’ preference to nest in tamarisk trees a “fatal attraction”: The dense branches at the tree crown are appealing because they offer stability for the nests. But seen from below — as they are by some predators, like cowbirds — the nests are much more visible than they would be in a willow. Cowbird attacks on flycatchers are three times higher for flycatcher nests in tamarisk than willows, he said.

So far, southwestern willow flycatchers have only met the salt-cedar leaf beetle in one watershed — along the Virgin River, which flows through southwestern Utah and Nevada before joining the Colorado River at Lake Mead.

There is anecdotal evidence that flycatcher numbers suffered because of tamarisk defoliation, Dudley said. “On the other hand, where restoration has been done in the upper watershed near St. George, those flycatchers nesting in tamarisk did a very interesting behavioral switch last year to nesting in the willows.”

Once in the willows, one of the trees with which they co-evolved in the first place, the birds tripled the number of chicks they successfully fledged the year before, when they were living in tamarisk trees. Deloach takes it as a sign that southwestern willow flycatchers will end up better off in the wake of the tamarisk-chomping beetles.

“I think salt cedar is very destructive in the ecosystems,” he said. “And I think there’s good evidence that the flycatcher is not going to be at all harmed by this.”