This photo taken by drone shows a washout caused by flooding on Montezuma County Road P in March. The abundant precipitation this winter has raised some concerns about flooding, particularly in the Town of Dolores.

“The river will break through above town and run down the highway and when it does my house is screwed.”

“When it gets above 6000 cfs [cubic feet per second] it breaks through about 5 miles upriver and goes over to the old channel by the hill and will flood the entire town.”

“I had to get flood insurance when I bought my house in 2017 even though I am on Hillside by the High School and it made no sense to me.”

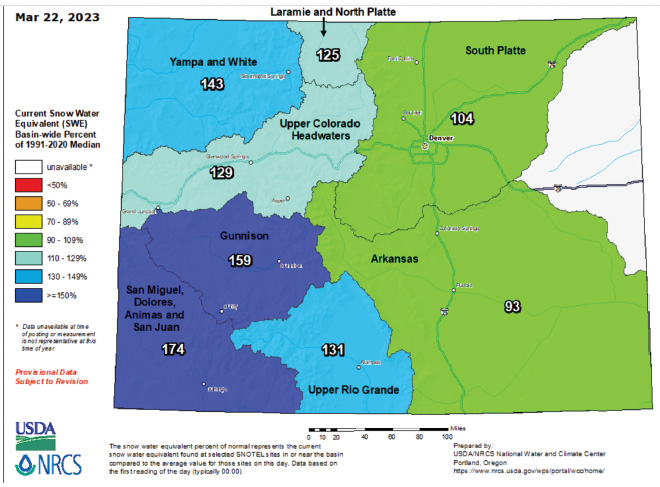

“All the old-timers say they’ve never seen this much snow.”

“They changed the channel and the original river flowed over by the hill, so when it floods it will run back over there.”

“My sump pump is already running 24/7 and runoff hasn’t even started.”

These comments from Dolores residents were made in public locations around Dolores in February and March.

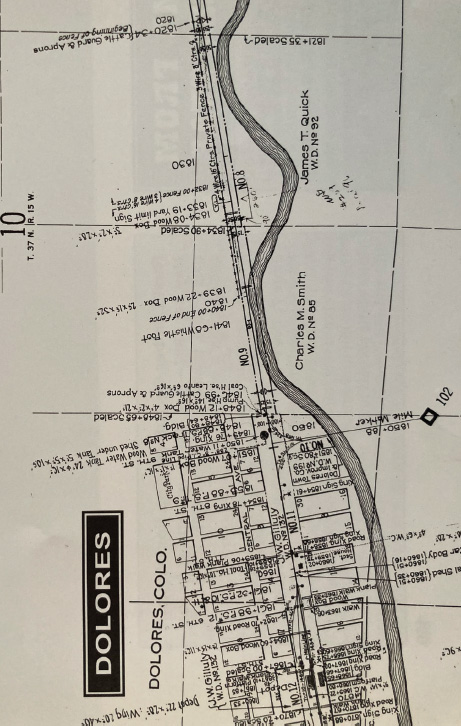

A map of the Town of Dolores in 1919, featured in Volume 6 of the Rio Grande Southern Story.

Past floods, in particular the notorious flood of 1911 – which did inundate the entire town of Dolores – are mentioned, along with speculations about how high the river will get during this year’s runoff, how much snow there really is, and whether there will be flooding in town.

As of press time near the end of March, not only was the Four Corners area expecting several more inches of snow, but areas in the county were experiencing issues due to high water runoff. County Road P was closed indefinitely on March 16 between Road 21 and 22 because of a huge pit caused by water.

“There was no sinkhole,” Sheriff Steve Nowlin told the Four Corners Free Press. “It was a washout. There’s a lot of water in that draw – it has washed out several times before.”

Highway 184 was closed on March 14 between the junction with Highway 145 near Dolores at Hilltop and the junction with U.S. 491 near Lewis. Water was running over the roadway, so the Colorado Department of Transportation closed it to commercial vehicles, with only local residential traffic allowed.

Plenty of rivulets and normally dry ditches in the county were running high and even flooding fields. Lost Creek was flowing double its median level for the end of March, as was Mud Creek, according to USGS data.

On March 19, the Dolores River reached 150 cfs in town, also twice the median flow based on records starting in 1896, according to USGS streamflow data. On March 25 the gauge was iced over.

McElmo Creek was flowing at 710 cfs at the Colorado-Utah state line and 408 cfs above Trail Canyon. The Mancos River had a flow of 265 cfs.

These flows are all above average for the date, demonstrating that melting has begun in the lower elevations, while the upper basins which feed the Dolores remain frozen.

Piles of snow

There are legitimate reasons for concern. Not in Cortez, which doesn’t sit on a river, and so far not in Mancos. However, there are some worries about possible flooding of McElmo Creek, which runs east and west through the county. The main fears, however, center on the Town of Dolores.

Locals say they can’t remember seeing so much snow piled in the Town of Dolores before this winter. Photo by Janneli F. Miller

Deanna and Val Truelsen, longtime Dolores residents, told the Free Press they’ve never seen snow piled so high in town, and precipitation and Sno-Tel data confirm that the winter 2022/23 season has been well above average. However, Deanna Truelsen said the Scotch Creek Sno-Tel is located right where snowplows pile snow, so she thinks it reads higher than it should.

River flows have been recorded by the USGS for decades, depending on the location.

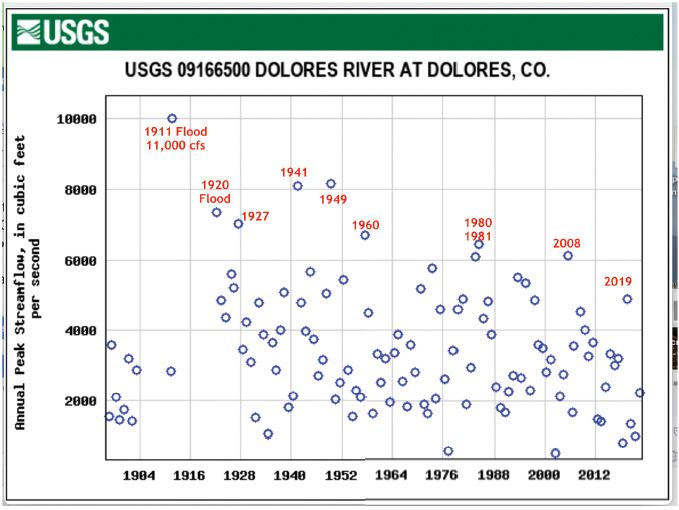

USGS has recorded and graphed data for the Dolores River beginning in 1896 (see graph on Page 6). The highest flow recorded was estimated by the USGS to be 10,000 cfs in 1911. Val Truelsen said back then they did not have any way to record the actual flow. Most locals say it was 11,000 cfs.

This 1911 flood event is widely known in Dolores, with residents aware that when the Dolores River floods, it has always been in the fall, not during spring runoff. This historic flood took place in early October 1911. Current worries about flooding stem from this event, with town and county residents sharing vague notions about how high the river needs to get to cause a flood. And where it used to flow.

In Volume 6 of the Rio Grande Southern Story, Russ Collman wrote, “After 3 months of intermittent heavy rain, early snowfall had soaked the mountain ranges surrounding Rico, and a great wall of water came down the Dolores River from the watershed on the south side of Lizard Head Pass.”

Additionally, the Silver Creek watershed released a “treacherous wall of water,” with disastrous results, including washing out the railroad section house at Rio Lado.

Dell McCoy, also writing in the Rio Grande Southern Story, Volume 6, noted that “every trestle or bridge below [the Gallagher Trestles in Rico] were either totally gone or had nothing but Colorado scenery visible at one end by the time high water had passed.” He wrote that during this flood the river had two channels between Kings Ranch and Rio Lado, a new bend in the river was formed at milepost 76.5 near the confluence of Section House Draw and the Dolores, and the high water also cut a new channel through an embankment.

According to an article in the Dolores Star on Oct. 6, 1911, “The heavy rains caused the river to raise very rapidly until Thursday evening around 8 pm when it broke through the bed of the Rio Grande Southern near the CM Smith house in the east end of town. The water followed the course of an old river bed and part of the current flowed out through town.” Early maps show the Dolores River turning north above what is now Eighth Street, where the CM Smith house was, passing by the current library and heading over towards the northern edge of the river valley at 11th Street, where the current high school is now located. This is upriver from town. The area was a swamp and slough beyond the eastern end of town (which ended at Ninth Street) where residents used to ice skate in the winter.

Callie Lofquist, a lifelong resident of Dolores, emphasized that the Dolores River never ran up against the north side of the canyon when interviewed by Shirley Dennison in 1989 for Our Past – The Portals to the Future, a two-volume oral history of Dolores published in 1994.

Don Akin and Andy Harris, lifelong residents of Dolores and descendants of the town’s original founders, were interviewed by Dennison in 1992 for Our Past.

Akin said, “The river used to run around there, too [Ninth St.]. Made a big swing from the hill behind the school house [on North 16th St.] and came all around through there.” Harris said, “When they had the flood of 1911, that fixed the town. There’s still some low places I don’t know about now- but they could be there sittin’ on top of these beams in these stores – There’d be water all over the place.”

Harris continued, “In 1911 it was just rainin’ and then it couldn’t make that big bend and come right down Main Street. That was the big bend of the river up here [east of Ninth St.]. Dennison asked: “So the river ran across the north hillside and came down Central Avenue to Ninth Street? Did they re-channel it during that flood?” Akin replied “O yeah” and Harris explained, “That old river isn’t near as crooked as it used to be. All of us has done some river work on that river.”

As development moved up the valley beyond 11th Street, this bend in the river was cut off and the slough was filled with tons of gravel. The Dolores High School is currently located in this area, which explains why it is subject to flooding. It flooded in 2019 when the Dolores River reached a high-water level just over 5,000 cfs. This also explains why the resident on Hillside had to buy flood insurance, since the area up against the northern hill above 11th Street used to be the slough.

This USGS graph shows flows of the Dolores River over the years. Source: U.S. Geological Survey

This area, as well as most of the current town of Dolores, is designated by FEMA as a “Special Flood Hazard Area” without base flood elevation. Mancos has a small area by the river designated a flood hazard area, but the City of Cortez doesn’t have any flood hazard areas.

The 1911 flood ran through Dolores at a depth of 1-3 feet, with the Dolores Star reporting that a small house floated out into the middle of the street, the south side of the Fourth Street bridge was taken out, and “Lost Cañon Creek was the highest known for years and flowed over the county bridge.”

Houses on the west end of town in what is now Joe Rowell Park were photographed surrounded by water.

Callie Lofquist told Dennison in Our Past, “I remember that the water was so deep across there [Main Street] and there was a man on horseback and he picked us up one by one and took us through the water to the hillside so we could climb the hill. We went up on the hill, where the water tank is now.”

Sonora Porter, who was 8 at the time, wrote in Our Past that “The Dolores River was raging along out of course and out of banks. People were excited about the woman living in a floored tent that was swept downriver, to be rescued as safe as if she was riding a raft. Homes and fields were somewhere beneath the swirling mass of debris. Trees, whole sides of buildings, part of hay stack and what looked like a dead cow went by.”

Nowlin told the Free Press, “The river was moved. It was up against the hillside. That’s why the water tables underground are so high. We also have water that comes down in every draw, all the way above Rico – Scotch Creek, Barlow Creek, Roaring Fork – all of those will feed into the Dolores.”

A changing channel

But could the 1911 flood be repeated? Not likely, officials say.

“It just depends upon what kind of spring warm-up we have, but I do not foresee any flash flooding at all,” Nowlin continued. “The biggest thing is that we don’t know. We have to wait and see what spring brings.”

Jim Spratlen, Montezuma County Emergency Manager, said, “If you look at the pattern of history, it happens every so many years and then it goes away. History repeats itself and that’s what we’re doing now.”

In the 112 years since 1911, there have been a number of high-water years – in particular 1941 and 1949, 1920 and 1927, early 1950s, 1960, 1980 and 1981.

The most recent high-water years were 2008, when the Dolores got above 6,000 cfs, and 2019, when it ran to 5,000 cfs.

In 1911 the river washed out 43 railroad bridges, causing the Rio Grande Southern to quit running for several months. The 1920 high water was above 7,000 cfs and flooded in Bear Creek, and the 1941 highwater of 8,000 cfs flooded some areas near Joe Rowell Park in Dolores, but since then no high water has flooded the town.

Snow Water Equivalent levels in the State of Colorado in March.

The Dolores River has not gone over 11,000 cfs since 1911. It has only risen above 8,000 cfs twice, and over 6, 000 cfs six times.

Spratlen said that “based on historical data to 1921, the Dolores River has technically never flowed over its banks.”

There are several reasons for this. First, when the river does run at high water it cuts new channels on its own, as it has been doing forever. Nature is an excellent modulator of river flow.

Dolores residents, local ranchers, Rio Grande Southern employees, highway officials and landowners up and down the Dolores River Valley have all observed and sometimes recorded changes in the river channel. Most of the time these changes do not interfere with human activities.

But sometimes they do, and the second reason a repeat of the 1911 flood is unlikely is because humans have been intervening in the Dolores River flow at least as long as the Rio Grande Southern began operations in 1891.

The April 28, 1906, issue of the Dolores Star reported, “The Rio Grande Southern has a gang of men at work changing the course of the Dolores River about a mile above town. This will throw the current against the south hill and away from the railroad which will greatly lessen the danger of the water breaking through the road and flooding the town.”

Spratlen said, “When the river is up at 7,000 cfs it has so much velocity we may find some areas in the bank that need attention.”

Val Truelsen said, “High flows mean more velocity and when a significant volume of water hits a bend with a high velocity, the bank can be eroded and the river can form new channels.” He said that since the high water of 1949 there has been a lot of work done to stabilize the banks. “I think there’s been over a hundred tons of riprap put along that river since the 1940s,” he said.

Montezuma County had a project installing riprap, shoring up the banks with rocks and trees. Truelsen said cottonwoods were no good for this purpose since they rot easily. Metal doesn’t rot, so in the 1940s old cars were put in along the riverbank to prevent erosion and overflow. These cars can be seen along the river in Riverside Park in Dolores, at the Dolores River State Wildlife Area and American Legion Park above Dolores, as well as at other spots upriver from town.

Ken Curtis, general manager of the Dolores River Water Conservancy District, told the Free Press that the Bureau of Reclamation built up the riverbanks in Dolores when McPhee Dam was constructed and built the berms that make up the river trail. Construction of the dam lasted from 1980 to 1986. The reservoir pool does fill up to the Fourth Street bridge in Dolores at high lake elevations.

“The highway [145] should be OK,” Nowlin said. “The river has been shored up by the Corps of Engineers.” He said this work is continuous, with CDOT upgrading worrisome spots regularly.

Truelsen also doesn’t think there will be much flooding in Dolores. “There’s more riprap now and the river channel is straightened.” He has spent countless hours shoring up the riverbank. Often landowners with riverfront property will use heavy equipment to dredge out spots or shore up embankments.

The fact that there is a lot of snow on the ground does not necessarily mean a high river flow. Yes, all that water has to come downstream, but it also melts into the ground and evaporates. A continuous warm spell, with sustained temperatures above freezing in the higher elevations, will cause a rapid melt-off. However, if there are intermittent warm spells along with continued bouts of freezing, the runoff will be slower and steadier, less likely to cause floods.

“It’s basic hydrology,” Spratlen told the Free Press. “We’re going to get a runoff, and a lot of rain,” mentioning that his department is in touch with weather experts. “We get a detailed spot check from National Weather Service. They call and alert me if there’s any significant weather we need to be aware of, and we get daily reports.”

But runoff is unpredictable. One situation officials all said could be troublesome is if warm rain falls on the snowpack. At the end of March the region was experiencing a cold spell, slowing the melting.

Debris flow

Nowlin and Spratlen both mentioned debris as a factor in flooding. Nowlin said, “There may be some isolated flooding depending upon any debris that happens to stop the flows of the rivers and creeks. If debris happens to hang up on a bridge it actually brings more pressure.”

Spratlen agreed. “We have various areas that we’ve been watching – all waterways, watersheds, creeks, rivers, and other areas where the heavy rain brought water into small areas. We’re monitoring all of these. We’re unclogging culverts, and we do debris management, removing debris from roadways and from rivers.”

June 28, 1949, was a good example of the dangers of debris, as reported in the Rio Grande Southern Story, Vol. 6. “A large tree came down the Dolores River, butt first, riding a six to eight foot wall of water which pushed it ahead like a battering ram. The sharp bend of the river, in the background, marked the confluence of Roaring Fork Creek with the Dolores River. The big tree floated around this bend and smashed though the tower end of bridge 75-A.”

Truelsen said he saw this happen as a boy. “Usually a tree will drag the butt end last, but this one came butt first and all the branches were splayed out, gathering more debris. That was a sight to see.” He said there are not any big trees like that left upriver, so this probably will not happen again.

Spratlen said the trouble now is mainly rocks. “Our terrain has got enough vegetation so we’re not worried about mudslides like Durango might have since the 416 fire. Waterways might get blocked with debris, so if any rock debris comes loose we have to be careful.”

While it might seem unlikely that a flood like 1911 could recur, local officials are busy preparing for the off chance of flooding.

Dolores Town Manager Ken Charles told the Free Press, “We’re cleaning out culverts, under the highway and in our underground drainage system. We’re digging snow off the drop inlets, the drainage grates at the surface level on town streets that help water eventually make its way to the river. We are working with the county to clear culverts east of town coming from Boggy Draw, and just today we called CDOT about a couple of culverts just east of town limits to get them cleared.”

Nowlin said he does his best to be aware of the current state of county waterways and other areas that might flood. “I’ll fly the Dolores and that will help us see if there is any debris. I do this every year.”

Another aspect of safety preparations involves rafting on the Upper Dolores. Nowlin said, “The public bridges are OK, and should be fine in high water. The problem is the private property bridges; those are the ones that can have problems.” He said part of the reason he flies the Dolores during runoff is to make sure there are no stringers or debris caught on bridges, which could not only impact flooding, but cause harm to recreational boaters.

Spratlen said, “Our biggest problem is rafters and kayaks that can’t duck under the bridges.” He said swiftwater rescue is an issue, and part of the county emergency response team includes personnel with swiftwater rescue training and experience.

Spratlen’s department is also busy observing the area. “We have some trigger-point areas we’ve been looking at. Mainly all watersheds throughout the county.”

He has crews out monitoring these spots daily. “We plan for the worst and hope for the best. We work with each municipality and neighboring counties. We have plans that we’ve had in the past: emergency response, alerts and warnings, emergency management, evacuation plans. You name it. We’ve got it. We’re refining it.”

His department meets regularly with town officials and emergency responders. “I have people out that are photographing, documenting all our areas and road grids that check all the culverts. Dispatch calls us if there are boulders or any other problems in the road. We monitor 911.”

Vicki Shaffer, the public information officer for the county, works closely with Spratlen. She told the Free Press, “We are using the Ready Set Go alert system. Right now we are in the Ready phase. Make a plan, pack up emergency essentials, gather up important papers and make a plan for what might happen if you need to evacuate. If we move to Set, that’s when people need to think about livestock, preparing their houses for potential damage and so on. The Go phase is the evacuation phase, where everyone needs to get out right away.”

Nowlin also emphasized preparation. “There’s no room for panic at all, there never is. It just depends if there are going to be pre-evac notices, if there’s enough time. The notices will come out on radios and Nixle.”

Shaffer said people should sign up for Nixle. The easiest way is to send a text with your zip code to 888777. You can also visit www.nixle.com and sign up for either text or email alerts. She noted that the internet and social media will have information too.

“We are posting on Facebook, on the Montezuma County Sheriff’s Office page, Montezuma County Emergency Management page, as well as the pages for Mancos and Dolores and the fire district pages.”

She said part of her job is correcting misinformation on Facebook. “There’s a few people who post incorrect information, and we’ve been able to reassure them with facts. For instance, some people are having water in their homes or basements. It’s the groundwater that’s seeping up, due to the high water table. That’s not flooding.”

This is currently happening in Dolores, since the town is built on a floodplain and many residences do have their basements filling and sump pumps running.

Dolores Town Manager Charles said Montezuma County has secured a sand-bagging machine, and sandbags are available for town residents or those living upriver to fill themselves. An information sheet is available on the Dolores town website, or for pick-up at Town Hall. Residents currently experiencing flooding issues can get empty sandbags at Town Hall during working hours, and sand to fill them at Joe Rowell Park. (Sandbags are to protect homes, not outbuildings or riverbanks.)

Plan ahead

“There’s not a whole lot of a threat,” Spratlen said of current conditions. “As we get into April and May we will set up sign boards all over the towns if necessary. Everyone is working together to see what resources are available.”

Nowlin added, “On the county website we are putting out safety instructions. The biggest thing is to plan ahead. Have a plan for water and goods if your road is impassable. Make sure you have everything you need for several days. Don’t enter the water! There will be evacuations if we need to, but I don’t foresee any of that right now.”

Spratlen wants the public to know that county officials and agencies are protecting the people. “We’re all for the public, and we know what we’re doing. We’ve got a really well-oiled machine and it’s working well and everyone communicates, everybody gets along. We’ve been doing it for years. We train constantly. We’ve got a really good emergency response team.”

Nowlin stated, “It will be OK.”