We’ve all seen it — that red tinge of dirt that covers the snow on Colorado mountains after one of our infamous dust storms finally subsides.

Ski resorts and backcountry skiers despise it because it can shorten the season, and the dirt gums up under skis and snowboards, making for a rough ride.

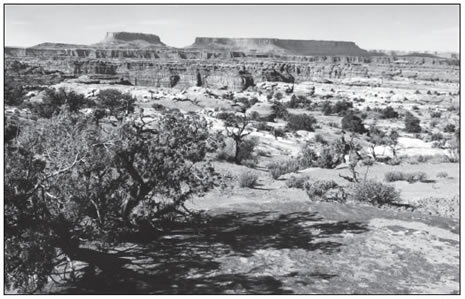

Dust deposition from Utah’s canyonlands is being blamed by some environmentalists for earlier snowmelt in the mountains of Colorado’s Western Slope. Photo by Gail Binkly

Water managers worry about the thermal effect red dust has on speeding up the snowmelt process that fills reservoirs feeding municipalities and agriculture.

Rafters are concerned it means less water for them, and water-treatment-plant operators in Aspen have blamed the dust for clogging their filters in the spring.

But where does this dust come from? Who’s to blame, and can anything be done about it?

A recent satellite image of the Western Slope provides a clue, making Utah a prime suspect. In the photo, a distinct red sheen can be seen on mountains stretching from Telluride to Steamboat. Meanwhile, the snow on the mountains of Colorado’s Front Range shows up as trademark white.

Some environmentalists are making the case that protecting Utah’s red-rock canyonlands from further development and motorized use would mean less dust on Colorado’s snows.

But while blaming Utah’s nearby desert country for early snowmelt would be convenient since it is often upwind from Colorado mountains, doing so ignores the bigger picture, which is quite complex, experts say.

In fact, according to Chris Landry, executive director of the Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies (CSAS) in Silverton, “the vast majority” of the dust on the snow does originate from the Colorado Plateau, a massive geologic feature that dominates the Four Corners region.

“Chemical and isotopic analyses of dust collected out of the snow show it is very strongly associated with the greater Colorado Plateau,” Landry said. “But, there was no real precision that it was linked to one specific township or chunk of land” in the area.

Its relatively large grain size proves the dust load is regional, brought here by prevailing winds mostly from the south and west.

Dust storms aren’t new to the region. Core samples from lakes in Silverton show dust deposition occurring for thousands of years. But the rate of accumulation increased dramatically after pioneer settlement and development began in earnest 150 years ago, according to some researchers.

Scientists from CSAS, the University of Utah, and the University of Colorado have analyzed what impact the red dirt has on snowmelt in the San Juan mountains since 2002.

Studies found that snow covered with red dust melts earlier and faster than adjacent snowfields that are white, given the same weather conditions, Landry said.

In 2005 and 2006, snowpack with a layer of dirt on Red Mountain Pass between Durango and Silverton and at other sites in the region melted 18-35 days earlier than more pristine snow in the vicinity.

In the spring of 2009, which featured a record 12 spring dust storms, studies showed that dusted snow melted 48 days earlier at test sites within the San Juan mountains compared to cleaner snow.

The accelerated and earlier melting is due to the high thermal properties of red dust, which readily absorbs solar heat while white snow reflects it. It’s similar to how wearing a dark T-shirt on a warm day has a sweltering effect.

Faster and earlier snowmelt from the dust can factor into how reservoir managers predict runoff volumes, explained Vern Harrell of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Cortez office, which helps manage McPhee Reservoir.

“This year was one of those marginal years where we are just on the edge of filling or not filling, so it did not really matter that the dust on the snow was making it melt earlier,” he said. “But had it not been there, it’s possible that the snow would have held back a little bit more.”

For boaters, that timing makes a difference. When floating the canyons on the lower Dolores River below McPhee Dam, premature runoff means recreational releases tend to come earlier in May when the weather can be less than ideal.

The snowfields in the mountains are like the regulating water tanks of the state. They can store more water, and longer, than a reservoir can. If the snowpack melts early, it tends to fill reservoirs faster, causing excess flows to be released downstream sooner.

During hot summer months, drawndown reservoirs can’t provide as much water for downstream habitat when it needs it most. Early spring runoff also translates to lower late-season flows for rivers and boaters across the Western Slope.

Another factor is that reservoir managers tend to practice a “fill, then spill” strategy. Due to a cooler spring this year, irrigation demand was low, prompting the reservoir to fill faster and therefore pushing up the date of downstream boating releases.

Lizard Head Pass and the Dolores Basin, which drains into McPhee, showed “quite a bit of dust on the snow on the northern slopes,” Harrell said. “The last four or five years it has become a factor, and I attribute it somewhat to the dry cycle we’re in right now.”

Trying to single out the effect of dust on overall snowmelt predictions is difficult because of the myriad other influences taking place simultaneously. Constantly changing conditions and weather can lead to surprising results. For example, Harrell explained, earlier melt-off from the dust might save water that otherwise would be sucked away by wind storms later.

“If you can get the snow off before it gets hit by all that wind, we might have more water,” he speculated.

One way to help reduce airborne dust is to establish more wilderness areas in desert regions, suggests Terri Martin, Western regional organizer for the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance. The non-profit environmental group is promoting wilderness conservation efforts in Southeast Utah to restrict activities such as oil and gas development, road construction, and off-road vehicle use that disturb the fragile desert soil.

“Wind storms are natural, but the amount of dust in the air is not,” Martin said. “We’re saying, if you want to control the dust, look at how the BLM lands in Utah are being managed.”

In Utah’s portion of the Colorado Plateau, 20,000 miles of off-road vehicle routes were recently approved by the BLM, she said, which could contribute to windborne dust and erosion by destabilizing the soil and its protective layer of cryptobiotic crust.

Oil and gas operations also exacerbate the dust pollution by disturbing large tracts of land and exposing it to wind, she said. According to SUWA data, 80 percent of BLM land within Utah’s Colorado Plateau is available for drilling leases.

“Wilderness designation will not solve the problem of dust on Colorado snow, but curtailing some of these activities is a step in the right direction toward mitigating the problem,” Martin said.

A series of meetings has been held in San Juan County, Utah, by U.S. Sen. Bob Bennett to discuss wilderness proposals there, but no legislation has been introduced as of yet. And the fact that Bennett was recently defeated at the state Republican convention in his effort to get on the ballot for a fourth term in the Senate may mean his efforts will stall.

Bennett had been gathering local input to develop a wilderness bill that would be modest in scope and palatable for locals in conservative San Juan County.

Meanwhile, a citizens’ bill called America’s Red Rocks Wilderness targets 9 million acres of Utah BLM lands for wilderness protection. The bill, which has 163 co-sponsors in the House and 22 in the Senate, is in the initial committee stage. “Colorado should have an interest in this legislation because we know that you love this area and it has a secondary benefit of helping to mitigate dust on mountain snowpack,” Martin said.

Researchers caution that not enough long-term data has been collected to characterize recent dust deposition on the San Juans as showing a definite upward trend. Also, the question of dust on snow causing increased evaporation (as opposed to melting) has not been answered, nor have claims that the dust causes increased sediment in creeks been scientifically proven.