Commissioners cite lack of detail in Outlook Resources’ plan

A proposal to mine a molybdenum deposit potentially worth billions of dollars in the mountains east of Rico was turned down June 11 — or actually June 12 — by the Dolores County Commissioners.

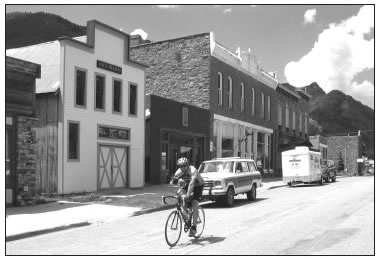

Recreation, tourism and residential growth now characterize the former mining town of Rico. On June 12, the Dolores County commissioners rejected a proposal for a molybdenum mine near the town. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

Approximately 130 residents packed the town hall to denounce the mine slated to be built on private land 1 1/2 miles from town in the Silver Creek drainage, the town’s water source.

During a six-hour meeting that began June 11 and continued past 1 a.m. the commissioners listened to a spokesman for applicant Outlook Resources describe the underground mine operation, then took public comment.

But in the end, the legacy of western Colorado’s former mining boom, which left abandoned mines, polluted mill sites, contaminated soil and toxic tailing ponds strewn across the mountains, doomed the plan.

“Mining is our past, but I don’t believe that it is our future,” said Rico Mayor Barbara Betts. “Mining jeopardizes the safety of our children, our water and our air. We are a small community of 225 residents, but we are a mighty force. If the board approves this, there will be a fight all the way.”

The commissioners took public comments for three hours, held a 20- minute executive session, abandoned a plan to continue the hearing at a later date, and then denied the application in a 3-0 vote, to raucous applause from locals.

They cited an incomplete application that failed to lay out the specifics of the mine’s impacts, and said the proposal was too speculative. Issues included industrial truck traffic through residential areas, uncertainty over milling sites, lack of financial backers for the project, the amount of water it would require, and safety issues.

Of specific concern was the applicants’ request for a 30-year time frame to explore and mine the site. State and federal permits typically are for 10 years, and assurances that those permits would be obtained at a later date were questioned.

“A 30-year time frame is too open-ended,” said Commission Chair Ernie Williams in voting to deny the project. “I do not like tying future boards to something they can lose control on, plus the environmental laws will just get stricter and stricter over time.”

Dolores County does not have zoning laws, and applicant Mark Levin, owner of Outlook Resources, argued mining is a historic right in the heavily mined region.

“I want to validate mine use for the property,” Levin said. “I am asking the commissioners to recognize mining as a use by right. The potential is for 200 to 300 high-paying jobs in the area and increased tax revenues for the town. I hope over time I earn the trust of the skeptics.”

“Why come to us now?” asked Williams. “Why not prospect first and come to us after you know what’s there?”

“Because no one will put up the money if there is a question of fundamental mining use for the property,” Levin said.

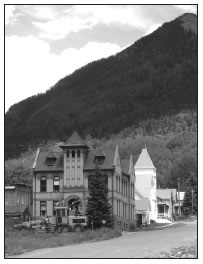

Rico is known for its scenery. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

“Colorado has already validated mining as a use by right, so I do not think this board has to decide on that,” Williams said.

Of those who spoke at the hearing, critics outweighed proponents 28-1.

“This town is based on recreation and beauty of the environment,” said resident Craig Spillman. “That is our use by right today. As a former miner I’ve seen the boom and bust. Remember what happens when the investment dries up and people are out of work.”

Resident Gary Reid agreed. “Rico was a mining town. Now it is a resident community. Colorado has a terrible mining legacy, and the contaminated soils and clean-up we have endured in Rico is a prime example.”

A contentious issue was that access to the proposed mine site is along Mill Road, a residential street. The applicant successfully proved that it is a historic route dating to the mining heyday more than a century ago and is therefore considered legal access.

“That was back then when there were no homes,” countered resident Patsy Engel. “Now things have changed; there are three subdivisions with 24 lots along that road now.”

Steve Garchar, a member of the Dolores County Planning Commission and the sole proponent who spoke out, responded that the extra tax revenues could be used for public-works projects such as a central sewer system, which Rico still lacks.

“Every person knew when they moved here that Rico had a mining history,” Garchar said. “These roads were built for everyone. This is a great opportunity.”

Val Truelson, a Dolores town trustee, said he is in support of mining, but urged denial of the application because it grouped substantial exploratory drilling with a major mining operation to follow.

“Those two activities should be applied for separately,” he said.

The speculative nature of the project drew a lot of criticism.

“He said he could mine molybdenum, or zinc or copper, or shelve it, or sell it to someone else. The ore could be processed in the next county over,” said resident Lori Adams “How does any of this benefit Rico?”

Levin explained that the lack of funding is a “chicken-and-egg” issue for mining. Bankers require promising exploratory core drills to justify the investment. Five such core samples done by the Anaconda Mining Co. showed good promise for molybdenum. Levin said 100 or more test holes would be required to verify the deposit, estimated to be one mile beneath the surface. Each exploratory drilling costs $1 million, he said.

The location of the mine incline — tunnels that deliver the ore out of the mine — was another unknown. One suggestion by Levin was that the incline would exit in La Plata County in upper Hermosa Creek, an area now being considered for wilderness protection.

Another option discussed was to slurry the ore in pipelines along the Dolores River corridor, “to perhaps private property in the high desert,” Levin said, estimating that such a slurry would cost at least $100 million.

Responding to opponents’ concerns, Levin argued that state and federal permits for mining the property adequately address environmental issues and safety. He added that mining would not likely begin for 10 or 20 years.

“This deposit is not going away,” he said. “The state has strict regulations that address every environmental concern here tonight. I’ll be a good steward of the land. If I don’t do this, somebody else will.”

This was the second failed attempt by developers to access the molybdenum deposit located a mile under the rugged Rico Mountains. In 2008, Bolero Resources Inc, of Vancouver, British Columbia, entered into contracts to purchase land for a mine in Rico, but the deal fell through because clear title could not be verified.

Test holes drilled in the 1980s by the Anaconda Mining Company resulted in estimates of 198 million tons of molybdenum ore at the site, owned by the Webster Estate. That could produce 273 million pounds of molybdenum, according to industry estimates, worth $2.4 billion at the current price of about $9 per pound, down from $35 per pound at the end of 2008.

The Rico deposit is estimated to rival that of the Henderson molybdenum mine near Empire, Colo., the largest producer of the metal in the world.

Molybdenum is an element used to strengthen steel and other metals. It is used to make auto parts, stainless- steel products, tools, liners for nuclear reactors and mountain bikes.