Wilderness areas are sometimes criticized as being mostly “rock and ice,” swaths of above-timberline terrain that is hard to get to and has little risk of development.

The lack of practical access for roads, home sites, logging, dams and mining make these protected wilderness areas less controversial and therefore easier to designate by Congress.

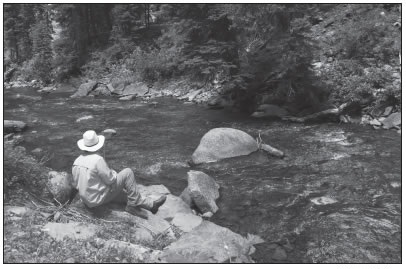

A fisherman tries his luck in the clear waters of Hermosa Creek near Durango. The popular creek and the surrounding watershed may be protected as a special management area if legislation to create that designation is successful. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

But mid-elevation forests and watersheds feature more biologic diversity, create critical wildlife corridors and, because they have easier access, are more at risk for development and overuse.

The Hermosa Creek drainage north of Durango is just such a place. The pristine forested basin with outstanding ecological values and the state’s purest waters is being considered for wilderness protection.

Located within the San Juan National Forest between Hermosa and the Purgatory ski area, Hermosa Creek is a popular recreation spot attracting horseback riders, mountain-bikers, hikers, kayakers, anglers, hunters and motorcyclists.

That multiple-use tradition can make negotiating for more restrictive public land management a difficult challenge. Add to that mining and grazing interests, water rights and roads, and the task becomes monumental.

Yet a consortium of local community leaders — from environmentalists and recreationists to water managers and miners — has proven that a collaborative approach and willingness to compromise can be an effective formula. Following nearly two years of monthly public meetings, a management plan has been put forward for Hermosa Creek with the blessing of everyone at the table.

“We all took the time to hammer out every issue piece by piece, and in the end we all gave up something and shook hands on a proposal,” said Jeff Widen, associate director of the Wilderness Society Support Center in Durango. “The final plan was forwarded to Congressman John Salazar and we hear that he and his staff are very interested” in introducing a wilderness bill for Hermosa Creek.

The proposal is two-fold. First, 50,000 acres of steep forested land and tributaries situated west of Hermosa Creek and east of the Colorado Trail would be designated as a wilderness area. The increased land protection prevents development such as new roads, logging, mining and dams, and bans motorized vehicles and mountain-biking.

Second, the entire watershed, from the headwaters north of Purgatory to the town of Hermosa, would be designated as a special management area (SMA) under the Forest Service to allow for additional protection and scientific study. The basin, with 150,000 acres, is one of the largest roadless areas in the state.

Compromise and grassroots community involvement were touted as the keys to a successful proposal for preserving Hermosa Creek.

The Hermosa Creek trails are enjoyed by a wide variety of users. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

The proposal came after months of work by a citizens group known as the Hermosa Creek Workgroup, which operated under the auspices of the broader River Protection Workgroup Steering Committee. The RPW was formed by the Southwestern Water Conservation District and San Juan Citizens Alliance, a nonprofit environmental group, to take a look at protecting and managing rivers and streams in the San Juan Basin.

The two groups, who often have very divergent views, decided to start open, public processes to find the best ways to preserve the special values of the area’s most outstanding waterways.

The Hermosa Creek Workgroup began meeting in April 2008, with Marsha Porter-Norton as facilitator [Free Press, May 2008]. Meetings were open to anyone, and the ground rules were civility and respect. The goal was to reach consensus on a plan, so votes were never taken.

After much hashing out of issues, the group managed to reach a consensus that involved compromises on everyone’s part.

Wilderness proponents had to scale down their wishes for a basin-wide wilderness area to accommodate for multiple uses in the region. The Hermosa Creek trail is a rugged single-track popular with mountain- bikers and motorcyclists alike, so that trail will remain open to all recreation.

At one point a Forest Service proposal included the Colorado Trail within the wilderness area’s western boundary, but after an outcry from the mountain-bike community, the boundary was tweaked so the popular biking trail is not included.

Mountain-bikers gave up access to a rough trail in Clear Creek, in exchange for keeping Corral Creek open.

The eastern boundary of the wilderness would be set back from Hermosa Creek one-quarter-mile to avoid the effective prevention of most water development on the creek.

Logging may be allowed, subject to Forest Service approval, in previously logged areas, with restrictions to protect water quality in Hermosa Creek, which carries Colorado’s Outstanding Waters designation.

The SMA designation includes a mineral withdrawal, meaning no new mining leases, but two mining interests on the north (300-400 acres) and southwest (1,000 acres) boundaries of the SMA were exempted from the ban.

“That was a tough pill to swallow,” Widen said. “But the compromise did bring support from the mining community for the plan.”

While not part of the proposal sent to Salazar’s office, public-land and water managers have also expressed interest in possibly earmarking Hermosa Creek for a Wild and Scenic River designation, which includes a federally reserved water right, prevents any dams and limits new diversions. The idea is that in exchange, other streams in the area such as the Pine, Piedra, Vallecito, Animas and San Juan rivers and would be kept open for possible development to meet future water needs.

“There needs to be potential somewhere throughout the basin for some reasonable water development that can address future demands,” said Bruce Whitehead, a local state senator and former executive director of the Southwest Water Conservation District. He was also a member of the Hermosa Creek Working Group.

The San Juan National Forest recently identified Hermosa Creek as a candidate for Wild and Scenic River designation due to its outstanding recreational opportunities and a unique pool-drop habitat for the rare Colorado cutthroat trout. In stark contrast, the Statewide Water Supply Initiative, a comprehensive study of potential water-development sites, lists a site on Hermosa Creek as a possible location for a dam and reservoir.

The Hermosa Creek stakeholders group agreed to hold off on discussion of Wild and Scenic designation to allow ongoing discussions of other rivers in the San Juan Basin to reach consensus and conclusions on best management practices there.

Workgroup processes are under way for the San Juan River – East and West Forks and the Pine River/Vallecito Creek. Workgroups will be convened later to discuss the upper Animas River and Piedra River.

“The district is not comfortable addressing those [Wild and Scenic River] issues at this point without knowing where other future water supplies could come from,” Whitehead said. “There may be a circling-back process on that topic that occurs after we have looked at all the values and water supplies throughout the [San Juan] basin.”

He added that the wilderness and SMA proposal being considered by Salazar protects the environment in the Hermosa watershed and also effectively preserves water rights held in the creek.

“There is agreement that any existing water rights can be used and maintained,” Whitehead said. “There is always concern from private property interests when you start looking at changes in federal designation. So it was a good educational and collaborative process with local buy-in that appears the right direction to go.”