Is the Four Corners ready for war games? The U.S. Air Force is targeting the area, saying the rugged mountains and steep valleys of Southwest Colorado and northern New Mexico are essential for low-altitude, nighttime training missions that keep American pilots sharp.

But locals fear crashes, deafening jet noise, frightened wildlife and livestock, and the disruption of the peace of rural life.

“I’d like to have a button in this room you could push that simulates exactly the sound of a C-130 flying overhead at 300 feet off the ground. My guess is that it’s not pleasant,” stated Andrew Gulliford, a Fort Lewis College professor, at a Oct 11 public hearing on the proposal in Durango.

“I’d like to have a button in this room you could push that simulates exactly the sound of a C-130 flying overhead at 300 feet off the ground. My guess is that it’s not pleasant,” stated Andrew Gulliford, a Fort Lewis College professor, at a Oct 11 public hearing on the proposal in Durango.

“The proposed map for these trainings includes the Weminuche Wilderness. San Juan wilderness offers three things: silence, solitude and darkness. There are too many people and resources at risk with this proposal.”

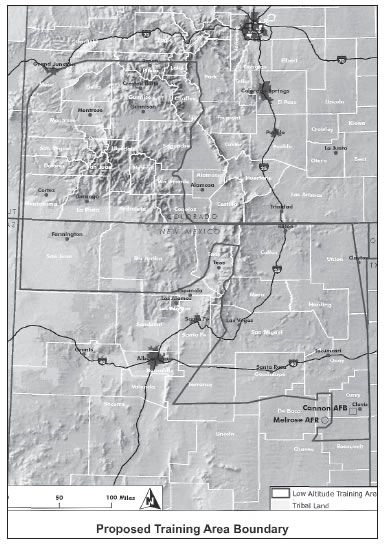

Under the proposal, 688 missions per year, or three every night, would depart from Cannon Air Force Base in New Mexico at dusk, with each sortie lasting five hours. Approximately 10 percent of the training missions would be flown between 300 and 500 feet above ground, 40 percent between 500 feet and 999 feet above ground and 50 percent between 1,000 feet and 3,000 feet altitude. They would fly over a vaguely hourglass-shaped area in northern New Mexico going north and west into Southwest Colorado over cities including Cortez, Mancos and Dolores.

The proposal was revised and the fly zone was made smaller after an earlier version was floated in 2010 and drew considerable comment.

The Air Force held 17 public hearings on the new proposal throughout the affected area. Durango’s gathering offered nearly unanimous resistance to the proposal, with only one citizen out of 45 showing support during a show of hands.

“I represent 50,000 people in La Plata County and I have not heard one comment in favor of this project,” said Wally White, a La Plata County commissioner.

The exception at the hearing was Zane Wood, who spoke on the importance of the U.S. military training missions.

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are at war, the enemy may be in this room and those that stand between us and the enemy need training,” testified Wood. “Regardless if you are woken up or your horse is scared, the military must train or the enemy will be at our door, kill our children and attack our women. We must sacrifice and I don’t care if you lose sleep. Unless you are willing to stand between us and the enemy, then you should support the military training, so I hope this goes through. I’m all for it.”

Citing a need for “less sterile,” more challenging mountain terrain to train pilots, Cannon AFB hopes to expand its low-altitude, night-time training boundary to include 18 counties in Southwest Colorado and 14 counties in northern New Mexico, including land in the Navajo Nation.

Under the revised plan, outlined as a proposed action in an environmental assessment, training missions would be only for the C-130J transport plane and the CV22 Osprey (a dual-propeller helicopter/plane hybrid). No one area would be flown over twice in one night, and the aircraft would not fly lights-out, to increase visibility for other planes.

The expanded fly-over range would be used for flight practice by the 27th Special Operations Wing based at Cannon AFB. Crews would be practicing low-altitude, inflight refueling between two aircraft, lowaltitude formation operations, simulated

drops, and the use of night-vision goggles. “Air-crew survivability in combat requires the constant exercise of perishable flying and crew coordination skills in challenging environments that closely simulate the conditions and terrain of actual combat,” the report states.

Air drops or parachuting would not occur, the Osprey would not perform hovermode maneuvers, nor would landings occur at local airports. Planes would return to Cannon or Melrose AFB following their overnight sorties.

The reasoning for the expanded Colorado range, according to Air Force Col. Larry Munz, is that “we need to be prepared by flying over larger areas never seen before, and our pilots need the experience of flying low in challenging terrain at higher altitudes where the air is thinner.” He added that “there is no indication of significant impact.”

Military preparedness is not all about war, said Col. Munz, but is for humanitarian purposes as well.

“We respond to humanitarian disasters, and we need the practice to be able to effectively drop off supplies in earthquakes and tsunamis zones like Haiti and Japan.”

During a meeting break, C-130 pilot Major Jeremiah McClendon explained that the mountainous Colorado area is preferred because “following modified contour routes is the most difficult thing we do. We fly low altitude not because it is fun, but because we don’t want to get shot, so we fly under the radar.”

Wanting further study

What concerns critics of the plan is the very large area that would be open to unannounced flight training at very low altitude, 300 to 500 feet above ground. Typically Cannon AFB uses set military training routes (MTRs) around eastern Colorado and southern New Mexico that stay the same, and are generally less invasive and more predictable for populations below.

The proposed changes to a larger area with specific routes unknown to the public warrant examination under a more-rigorous process and the issuance of an environmental impact statement, according to opponents. They say research is needed to identify no-fly zones such as cattle and sheep operations, wilderness areas, mountain communities, tourist areas, avalanche zones near people and roadways, cultural sites and wildlife habitats- such as those of the Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep, mule deer and elk, which are known to experience increased stress due to low-flying aircraft.

“An EA is a low-ball, quick and easy way to do this,” said Gulliford, an environmen tal studies professor at FLC. “This study is a joke, patched together from dated studies from other areas. The citizens said no before and are saying no again because the impacts are extraordinary. An EIS is needed that addresses concerns by county and community, not just one map” showing a new training area.

Because the Air Force declared a finding of “no significant impact” in its environmental assessment, a more comprehensive environmental impact statement is not required under federal environmental law.

Stephanie Strine, Cannon AFB publicaffairs officer, said concerns are being listened to and that the flight plan and boundary were adjusted based on comments and concerns heard during previous community meetings in 2010.

“The map when we started was bigger than now,” Strine said. “Based on community feedback, it is smaller, so comments last time affected the boundary.”

For example, American Indian lands in the Taos, N.M., area were avoided to protect cultural sites and communities. Southeast Colorado was removed from the proposed flying range due to public concern as well as areas near Aspen where there is sensitive mule-deer habitat. Strine interprets a larger, low-altitude training zone as less invasive than the traditional, more predictable military training routes.

“It is a less-concentrated impact when training is conducted in a larger area,” she said.

‘We can’t see them’

The unknown routes of the proposed low-altitude training area are a safety concern for commercial and private pilots. Military aircraft don’t necessarily communicate their positions and flight plans with civilian or commercial planes, according to a local pilot.

With advanced, long-range radar systems, the C-130 and Osprey can monitor other planes far in advance and adjust course. But civilian and commercial aircraft don’t necessarily have that capability.

“They can see us, but we can’t always see them, so communication is key,” said Joe Gemperline, a general aviation pilot in the Durango area. “It is quite a shock factor when you come over a ridge and see a C-130 climbing toward the same pass.”

Gemperline said a separate, dedicated radio frequency is needed to warn commercial and general aviation pilots of military flight activity in the area.

Michael Lavey, a Navy veteran from Cortez, testified that the scope of the proposed flying range seemed too broad.

“It seems excessive, too many sorties, and the altitudes they are talking about are too low,” he said. “I moved to Southwest Colorado for the peace and quiet and I worry that this will jeopardize that. It sounds like their minds are already made up.”

The proposal states that heavily traveled civil aviation corridors, airports and landing strips would be avoided.

Ranchers face burden

Cannon AFB has set up a claims office for livestock losses from low-flying military aircraft. Public-relations officer Strine said the program will adjust flights to avoid sheep and cattle operations during calving, branding and herding when the animals are particularly vulnerable to stress and stampede. But that ranchers must contact the base with the specific locations and times to avoid that area.

“We fly in rural areas and avoid settlements, but there are times when we don’t see a community until it is too late. If that happens and a horse runs into a fence, then contact us and we will take it into account and stop flying over that house,” she said.

The number to call for ranching concerns and claims is 575-784-4131.

Ranchers don’t have time to think about military aircraft when they are gathering their herds, responded Carol Miller of the Peaceful Skies Coalition, a group fighting the proposal.

“We want to know where and when they are going to fly,” she said. “The Air Force has plenty of mountains on their bases in New Mexico, Nevada and California. Now they want Southwest Colorado mountains so they can militarize the entire U.S.”

Dan Randolph, executive director of the non-profit San Juan Citizens Alliance, said the flyovers are an unfair intrusion for local ranchers.

“It is a huge burden to the ranching community to call Cannon regarding livestock issues,” Randolph said. “There needs to be a better method, identified in an EIS, for that system. A lot of these rural areas do not have phone service.”

Ned Harper of Dolores cited a Diné College study of the impacts of low-flying military planes on sheep-herding activity on the Navajo Nation.

“People were terrified, sheep ran in every direction, horses ran in every direction, hotdog pilots fly lower than allowed,” he said. “Bringing the military here is too invasive.”

Mike Olson, a former Navy pilot, agreed that the location was wrong.

“We used to fly fast and low in similar mountains and this is not the right place; it is quiet here, a very important and special place,” he said. “Go to Nevada and California where they are set up with ground-based radar to pick you up, go to places with resources already in place to get the training, we don’t need more areas for training.”

Pristine mountains

Regarding noise, the Air Force’s studies report that overall operations would not exceed noise standards identified by the EPA as a threat to public health and welfare. Single- exposure noise levels generated by the C-130 and CV-22 Osprey could be as high as 98 decibels and 90 decibels respectively.

The study calculates that persons sleeping in a residence outside the avoidance areas could be awakened once per year by lowflying aircraft, or once per two years if the windows are closed.

The potential for crashes or refueling accidents also was a worry for meeting attendants. “To pick an area like this to practice refueling is irresponsible – it puts our headwaters at risk if gasoline is spilled,” said Miller of the Peaceful Skies Coalition. “This plan is trying to create a giant military training route.”

Added Judy Harris, “If there is a crash, what system is set up in our community to deal with it?”

Flying such low missions could also affect future wilderness designations, which specifically prohibit the noise and pollution of motorized intrusions.

“Establishment of low-level flight paths could preclude areas from protection,” said Randolph, of the San Juan Citizens Alliance “People here are already impacted by federal energy actions; this military fly zone would add to the cumulative impacts. There has been no discussion of hunting and fishing impacts either.”

According to the Air Force’s EA, “Threatened and endangered or candidate species locations and critical habitats identified by management agencies would be avoided by a minimum of 1,000 feet altitude.”

The pristine, wild nature of the San Juan Mountains should be protected, said others.

“A previous speaker said we have to sacrifice, but if we continue to sacrifice the cougars, bears, elk and solitude of our wilderness areas, what will we have when it is done?” said outdoor enthusiast Amy McClintock. “Let us not say, ‘Be damned!’ to the tourists who come here for the solace and the wildlife. I request that the proposal be withdrawn.”