After two short years in operation, Dove Creek’s biodiesel plant has run out of fuel. The plant closed its doors in October 2010, citing financial hardship and a flailing economy as the main culprits.

“Basically, the biodiesel market crashed, and then commodities,” said Erich Bussian, current CEO of San Juan BioEnergy, the company operating the plant. “We were carrying just too much debt.”

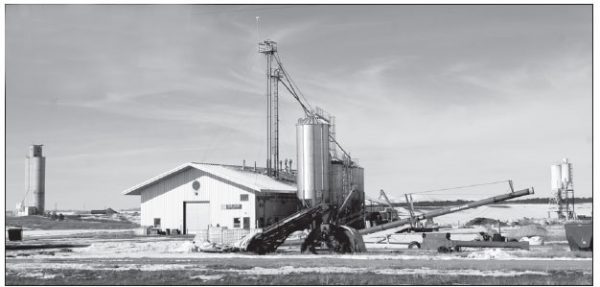

Dove Creek’s bioenergy plant, which was launched with great fanfare in 2007, is no longer operating. Its directors are hoping to find a new company to buy the facility. Photo by Aspen C. Emmett

The plant, located on the edge of town at 7099 County Road H, now stands empty, save for a few sacks of rotting seeds.

The closure affects some 60 farmers in the area, as well as a community of hopefuls who had expected the facility to give a much-needed economic boost to the area. The plant will not re-open under the current ownership, and its future remains uncertain, with its assets slated for auction this spring.

“Most farmers know the status,” Bussian said. “And I want them to know we are working hard to find an appropriate buyer.”

Great expectations

Touted as the eco-friendly solution to energy demand, biodiesel is a domestic, clean-burning alternative to petroleum based high-sulfur diesel fuel. It is derived from plant seeds pressed into oil and then processed into a fuel that can be burned in place of the highly polluting diesel. The few by-products of the process are non-toxic and can be used for other purposes, such as livestock feed from the meal and seed hulls.

San Juan BioEnergy’s Dove Creek facility was the result of environmentally considerate innovations by Jeffrey Berman, who was the company’s CEO during its concept stages in early 2005.

The plant came to fruition with production starting in 2008 on the high hopes that a new cash crop could transform the economic outlook of Dolores County and beyond. More than 200 people, including dignitaries such as then-Gov. Bill Ritter and then-U.S. Rep. John Salazar turned out for the Sept. 8, 2007, groundbreaking.

Farmers from Dolores, Montezuma, La Plata, San Miguel and San Juan (Utah) counties were recruited to produce sunflower and safflower crops for the plant.

It was a green gamble that made sense for farmers looking to increase their bottom line by growing a new crop in rotation with bean and wheat production on area drylands, according to Dan Fernandez, CSU extension agent for Dolores County, who also serves on the board for San Juan BioEnergy.

The switch to sunflower and safflower crops required very little modification to the equipment farmers were already using, and was considered a good rotation with bean and wheat harvests. A simple finger-like extension added to the front of combines made it possible to harvest the hearty crops.

“You didn’t have to spend a lot of money on your equipment to do it,” Fernandez added. “There were just a few slight modifications.”

The first year, 80 acres of land were planted with three varieties of sunflowers in order to see how they would do, Fernandez said.

“That did very well, and crop production continued to increase,” Fernandez said.

By 2008, the plant was offering 20 cents a pound for sunflower yields, according to SJB’s website. For a typical crop of 900 pounds per acre, that meant a gross of $180, compared to a $134-per-acre gross for wheat or $165 per acre for beans.

Crop production jumped from the 80- acre test run in 2005 to upwards of 18,000 acres of local farmland by 2009.

But 2009 also brought with it a slew of problems for the plant, and with the national economy struggling, things started to unravel.

An unforeseen drop in demand for the fuel complicated matters further for SJB, when the bottom fell out of the biodiesel market, forcing the plant to refocus on producing food-grade vegetable oil in order to survive.

“There was a perceived – and it turned out to be real – shift in the demand for biodiesel,” Bussian said.“We were waiting for things to turn around, which of course they did not.”

The decline in enthusiasm for biodiesel was reflected in uncertain funding, and despite efforts to evolve and adapt throughout 2008 and 2009, the facility faced defeat.

“The [biodiesel] tax credit was only being renewed by Congress on a yearly basis,” Bussian explained. “We never knew if that credit would be there the following year.”

An inconvenient truth

Research scientist and sunflower farmer Abdel Berrada. Ph.D., said despite good intentions and enthusiasm, the plant operation came up short, leaving farmers to wait for checks, and in his case, still holding the bag.

“They still haven’t paid us for 2009,” Berrada said in mid-February of 2011. “I don’t think they had enough financial backing from the start.”

Congressman Salazar managed to procure $296,977 in stimulus funding for the plant in March 2010 to help it cover costs, but even that proved to be only a stopgap measure.

In September 2010, Bussian was appointed the CEO of SJB, and Berman stepped down, taking a place on the board of directors. One month later, the plant closed its doors, and production came to a halt.

“It didn’t help that it was at the start of the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression,” Fernandez reflected. “It’s difficult to see because a lot went into it.”

San Juan BioEnergy now faces an uncertain future, with outstanding property taxes and financial obligations to Weber Industrial Park and numerous creditors, Bussian said.

“We are working hard with the banks to bring it to auction,” he said.

Forging ahead

But not all was lost. Farmers who already had safflower and sunflower crops in the works for 2010 found that those products were still in demand.

“Sunflower prices are still very high right now,” Fernandez said. “And the farmers are still very engaged. The farmers are fine. Alternative markets have been found.”

Berrada confirmed that he was able to find a buyer for his 2010 crop yield – and that it came with a prompt paycheck.

“There is still a market out there,” he said. “We have had good crop yields – they’re well adapted to the area and the climate.”

Plants like High Country Elevators in Dove Creek and Adams Group, an agricultural commodities firm in northern California, are offering prices that are comparable to or better than what SJB offered, Berrada explained.

From his 20-acre plot, he said, he produced more than 35,000 pounds of product in the 2010 rotation.

“So, yes, it’s still very worthwhile,” he said. “And they [Adams Group] said they would buy all the sunflowers they could get from this area.”

New horizons

Alternative buyers may be the temporary solution that the farmers needed, but locals haven’t given up hope that the Dove Creek plant will make a comeback.

Berrada believes that there is still a place for the facility in the community if it’s able to adapt and evolve. He suggested that the plant will need to reassess a number of things aside from funding in order to guarantee sustained success.

“They need a new business model,” he said. “They will need a lot more crops to sustain the plant. If local people have ownership, it would make a big difference.”

Berrada estimated that it will require at least 40,000 acres to produce the 1.5 million gallons of oil needed to drive the Dove Creek operation.

Additionally, further research is needed to determine just how much the dryland soil can support sunflower and safflower crops over time.

“We have a good feeling for what to expect,” Berrada said. “But it takes several years to get the good data.”

Because the plants have roots that extend six to seven feet into the ground, they can take quite a toll on the nitrogen supply. In drier-than-normal years, production can deplete the soil so thoroughly that it may require a more frequent rotation with other crops or even allowing the land to lie fallow for as long as three years.

And although the crops were originally promoted as dryland-friendly, it would dramatically change the production if water could be added to the equation, he added.

“They [sunflowers and safflowers] respond really well,” Berrada said. “You get two times or more with irrigation supplement.”

Fernandez is also optimistic about the future, acknowledging that there is still a need for research development and a plan as farmers and investors move forward.

“We have a new crop for our dryland that will be around for a long time,” Fernandez said. “I’m hoping the plant can be sold and get going again. This is something that can really benefit this area.”