In an effort to learn more about discrimination in the Montezuma-Cortez public school systems the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission invited Native students and parents to a hearing in Cortez. It was one of nine hearings held in border towns surrounding the Navajo Nation, including Cuba, Albuquerque, Gallup, Holbrook, Winslow, Flagstaff, Page, Blanding, and Farmington.

Leonard Gorman, director of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission, listens to testimony during a hearing on race relations in the public schools. The Cortez meeting was one of nine held in border towns around the perimeter of the Navajo Nation in March. Photo by Sonja Horoshko.

Testifying before the commission opens the door for individuals to tell their stories to a sanctioned entity where they can seek authoritative advice, air the complaint and possibly seek further legal help. This is the first step to identifying issues that may otherwise go unnoticed or be dismissed as inconsequential by officials in border towns. Predatory lending, voters rights, funerary practices, racism in the schools or other institutions are all topics of interest to the HRC.

“I’m a historian,” Jennefer Denetdale, NNHRC chair, said. “I understand the link between the poor infrastructure on the Navajo Nation and how it accounts for more dependence on border towns.

“Seventy percent of Navajo money flows off the reservation as a whole,” she said. An even higher percentage leaves the reservation in areas where access to border towns is more concentrated and direct. “Thus payday loans and pawn industries are two areas we investigate and, if possible, resolve the issues. I’ve been on the HRC for seven years now and I see encouraging signs.”

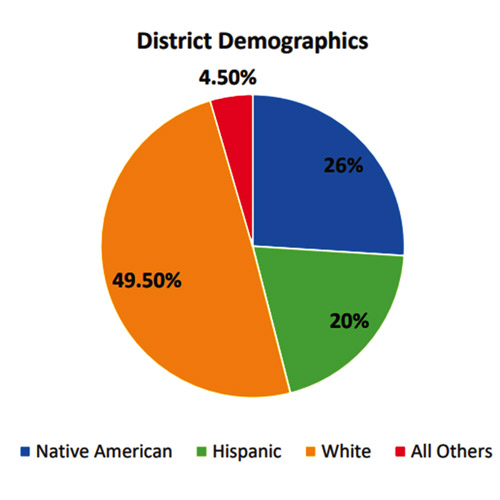

Of students enrolled in the Montezuma-Cortez RE-1 School District, 26 percent are native, 20 percent Hispanic, 49.5 white and 4.5 other ethnic groups. The native population is split evenly between the Navajo and Ute Mountain Ute tribal affiliations.

“We hold these hearings in good faith. People bring their issues to us. Yet, understandably, some people are afraid to speak in public about their experiences,” Denetdale told the Four Corners Free Press. “At hearings we are also able to raise awareness about other methods of registering a complaint in private – written form or online or how to discuss experiences in person or over the phone with our office staff. It is always a productive time for the commission.”

A backstory

Cortez resident Art Neskahai, Diné chairperson of Southwest Intertribal Voice, spoke at the hearing about his experience when his children began attending schools here in 2001. When he enrolled his children, they were immediately placed in the Individualized Education Plan without his consultation, he said.

“My children felt stigmatized by the separation from regular classes. It was assumed they didn’t speak English because we had just moved from Shiprock to Cortez. They stayed in those classes nearly all their school years. The IEP classes were supposed to give individual attention to basic skills but it didn’t seem like they did to me.”

Re-1 board member Lance McDaniel, who attended the meeting, told the Free Press that the IEP is a plan developed “between teachers, counselors and parents for the benefit of the child. Districts do get extra dollars for children with IEPs, but it does come with a stigma attached. Most IEP students are typically [children] with behavioral issues or kids with disabilities. Art had a valid point if his children were kept in an IEP for the length of their time as students.”

During those years Neskahai got involved with the school. He attended curriculum and school board meetings where all the decision-makers and administrators were white, he said. “I tried to address the issues, the lack of transparency about Title VI and Johnson O’Malley funding, the law passed by Congress in 1934 to subsidize education and other services to Native Americans, especially those not living on reservations.”

Neskahai told the Free Press he couldn’t understand the administrative bureaucracy, “It was hard to untangle. I couldn’t get anywhere. Then I organized on my own to get a Human Relations Coalition here in 2006.”

“Today, I have hope,” he said. “I believe the native community is strong enough, more confident and that organizing [the coalition] again could help build a good relationship with the school system and local governments. Maybe we could even see an audit of the Indian funding, to learn exactly how it is spent.”

Reaching out

Today, the RE-1 district reaches out to Native parents with multiple efforts designed to strengthen resources for native families. The Indian Policy and Procedures Presentation, a document produced every year, is found on the RE-1 website by its acronym, IPP DATA Presentation. It’s the place where parents can find facts about how native students, identified as Navajo or Ute in the graphs, are performing in language arts and mathematics. It is very accessible, showing bar graphs with text for all grade levels, and compares the current year to two previous years. Trends in performance levels are clearly visible.

Opportunities for parents to engage directly with the school in matters regarding their child’s education are offered through the Communication Support Committee and the Parent Advisory Committee for Parents of Indian Students.

This graph shows demographics of students in the Montezuma Cortez Re-1 School District.

While parents are encouraged to attend the monthly board meetings they are also invited to participate in the spring Parent Accountability Committee for parents of Indian Children, where their input and the needs of the native students can be discussed with administrators and teachers.

In addition, the IPP document outlines mechanisms of support offered by the school district that ensure inclusive cultural identity and awareness programs are available to all students in all grade levels. The Native American Club provides access to off-campus cultural events, brings cultural programming to the schools and continues to support students attending the national American Indian Science and Engineering conference each year.

The IPP document is very comprehensive. It provides a lengthy amount of detailed information in a clear and concise format and it is easy to access online.

A curriculum complaint

Although the Cortez meeting was sparsely attended, one parent drove from Durango to talk with the commission about the curriculum at her daughter’s middle school, which does not include native history, or a cultural point of view. No hearing was held in Durango because it doesn’t adjoin the Navajo reservation.

“My daughter is disengaged,” she said, explaining that the gap in presenting historical diversity hinders her daughter’s progress and self-esteem.

“As a parent I want my child to be engaged. I do not think the curriculum provides that for a native student. The school does not believe that colonization is a favorable topic,” she said. “The school does not believe that native history is relevant.”

Gorman asked for context.

“Jamestown,” she said. “The curriculum does not mention what happened to the Native people and culture at Jamestown. I supplement my kids’ education, so naturally they question these assumptions, the gaps. I grew up in a border town, Winslow. I recognize what normalizing behavior is. Many parents are in the same situation but do not speak up.”

She added that she feels the Title VI funds, intended to support native education in public schools, “may be being used for all minorities, including LGBTQ.”

Denetdale suggested she consider filing a formal complaint with the NNHRC. There will be more investiga tion into the use of funds if she includes a specific incident about funding in the filing.

Understanding history

Denetdale graduated high school in 1976 from Tohatchi’, N.M., on the reservation. “I had no inkling of Navajo history until college, when professors like Lucy Tapahonso introduced me to my own history. Now, 40, 50 years later, we’re still dealing with this issue, Our children do not know their own history. It is not just what our children need, but what all students need to understand history.”

Each hearing has drawn complaints about the lack of native curriculum and cultural sensitivity in the classrooms, the commissioners said.

Gorman describes Durango as the place where Dibé Nstaa, the Navajo northern sacred mountain, overlooks the community, and therefore “we are grounded in the facets of being Navajo because Dibé Nstaa is there,” he said. “To focus on these thoughts about native history and education where the community has a territorial view of the Navajo is appropriate, especially for Ute and Navajo persons.”

The commission set aside other engagements during the current fiscal year to focus on these concerns as a result of an incident in Cibola High School in Albuquerque, N.M., when a teacher was placed on leave for allegedly making a culturally insensitive remark to a student and snipping another student’s hair.

“Clearly cutting a student’s hair was an assault, a physical assault on a student,” said Denetdale in her opening remarks. It happened during a Halloween celebration at the school in late October 2018. The ACLU has now filed a lawsuit on behalf of the student’s family.

In a letter sent to the superintendent of Albuquerque Public Schools the following December, Leon Howard, legal director of the ACLU of New Mexico, wrote, “Anyone with even an iota of cultural awareness knows that in Native American cultures hair is sacred — particularly for women. Beyond that, the cruel implications of …[the teacher’s] actions hark back to the era of Native American boarding schools, when the cutting of Native students’ hair was a form of punishment inflicted by school masters in a racist attempt to strip children of their heritage and culture.”

Gorman reiterated that the schools everywhere need to not just talk “about” natives and offer extracurricular activities, but actually “recognize various aspects of our cultures, teach cultural values and language equally in the curriculum.

“At the core of the issue is the Western culture telling us, ‘You can’t be different’,” said Gorman. “But all people have a right to be unique and different.”

Renewed efforts

Years ago the Human Rights Commission made great progress working with the school system in Southern Utah, Gorman said.

“It was good work and now it has slipped. Those good works have to be renewed again. The system reverted to its old ways. We let our guard down. We have to rekindle our concern. We have to ask how Indians are being treated in all schools, including Navajo Nation, Bureau of Indian Education, public, private and parochial.

“We have been to Cortez several times for hearings on this and other topics and hope to foster a good relationship and communication with the school system.

“Everyone has a story. It is the essence of human life. We have to treat each other respectfully and interface with other governments and groups.”

For more information on the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission and how to file a complaint visit their website, www.nnhrc. navajo-nsn.gov or call 928-871-7436. The Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission is located in St. Michaels, Navajo Nation ( Arizona).