A child peeked out from behind the serape blanket covering the door of the shack where Marlene Kerley and her three children live. Her home is located behind a small rocky escarpment that hides her from the view of tourists driving the scenic highway in the Painted Desert to the Grand Canyon in Arizona.

Broomstick dowels served as the posts to hold up her roof, while layers of towels covered the windows above her children’s beds. The stove pipe intersected the roof near the broomstick. There was no plumbing and only a plastic dish pan for a wash basin.

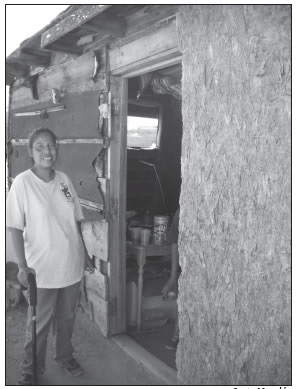

Marlene Kerley stands at the door of the shack where she raised her three children on the western side of the Navajo Nation. Housing remains a problem on much of the reservation as younger generations seek to abandon traditional hogans for more modern shelter. Photo by Sonja Horoshko

Every fall she wrapped the home inside and out with plastic that to keep away the snow and cold.

Walter Phelps of Leupp, Ariz., organized a house-raising project when he learned about Kerley while campaiging in the rural Navajo area during his successful bid to represent the Navajo people of Cameron, Coalmine, Leupp, Birdsprings and Tolani Lake as their council delegate in the new 24-member legislature.

“I do feel that Marlene’s situation is much more common than leaders want to admit,” Phelps said. “Navajo’s situation can be compared to other tribal communities, especially San Carlos here in Arizona, who I know have some serious housing needs as well.”

Kerley walks with a cane. She is hopeful that her dislocated hip is healing because of the care she receives from Indian Health Service in Tuba City, 28 miles away.

That care feels right, even hopeful, unlike the community assistance she requested at her chapter for repair of the leaking layers of second-hand roofing material that did not materialize. “I have been asking for help from our delegates and the Navajo Housing Authority, but no one responds to me.”

Although Kerley fell through the cracks of public assistance she persevered, raising her family in two lean-to rooms built with her own resourcefulness, nearby refuse at a transfer station, and materials cast-off from neighbors.

“Mr. Phelps came inside to talk to me about our community issues. It was the first time anyone had come to talk to me,” said Kerley. “I showed him the pole holding up the roof, and the mold growing on the beam there. I told him the truth about home conditions and showed him mine.”

Substandard conditions among Native housing are staggeringly common. April Hale, communications manager for the National American Indian Housing Council in Washington, D.C., provided statistics to the Free Press showing that 1 in 5 Native Americans live in overcrowded homes and on some reservations, nearly 25-30 people live in a three-bedroom home.

“About half of Native American homes are considered inadequate by any reasonable standard and less than half of all reservation homes are connected to a public sewer,” Hale said.

Although 20 percent of Indian homes nationwide lack complete plumbing facilities, on the Navajo reservation, nearly 31 percent lack complete plumbing.

Housing and Urban Development defines a home as substandard if it is dilapidated and does not provide safe and adequate shelter, endangers the health, safety or well-being of a family in its present condition, has one or more critical defects, or has a combination of intermediate defects in sufficient number or extent to require considerable repair or rebuilding.

It is also considered substandard if it does not have operable indoor plumbing or a usable flush toilet, bathtub or shower inside the unit, no electricity or inadequate, unsafe electrical service; no safe, adequate source of heat; or if it should, but doesn’t, have a kitchen.

Jack Colorado, current and outgoing council delegate representing Cameron Chapter, said the first he heard about Kerley’s situation was at a chapter planning meeting when she requested help. “I was told the discretionaryhousing funds at the chapter were depleted. I suggested she see the IHS because sometimes they help with environmental issues, like the mold in the inside of her home. After that, I never received any updated information on her.”

When Kerley welcomed Phelps into her home he says he was shocked “by her living situation and how kind she is,” said Phelps, “even in this circumstance.”

Kerley showed Phelps the documentation for her home-site lease and requests for help, telling him, “I paid for this.”

Initially, when he discussed her circumstances with his staff and family, “I just wanted to repair her roof, patch it to keep rain from coming through, stop the mold and mildew. But one of my staff members took a camera over there to see for herself. She literally cried when she returned after meeting Marlene and seeing how she fell through the cracks of the bureaucracy.”

The staff member challenged him, asking how he thought walls that weak could hold up a new roof. Then, he added, “I asked her and the staff if they are suggesting I build a new house? The answer was, ‘yes.’ I asked them in return to volunteer, back me up.”

That was the turning point. The group announced the project as a house-building event, hoping to attract the volunteer construction muscle and the skill they needed to erect the framing for sides and roof in one day.

Phelps went to the Navajo Housing Authority with a pick-up truck and a flatbed. He was sent out to the material yard behind the offices where he was told to load up whatever he needed.

“I took everything I could think of to get the job done, even a doorknob set and some roofing,” Phelps said, but he wondered if the Navajo people would come to help one of their own.

Early on the morning of Sept. 4, Phelps drove over to Cameron, 82 miles north of his home at Leupp on the reservation. Turning in to the site on the rocky road, he saw 15 vehicles parked in a circle around the stem-wall foundation.

Men in work clothes with tool belts strapped to their hips waved at him. Women pitched tents for cooking. Teens from the Church of the Nazarene in Flagstaff unfolded tables and chairs, and an elder uncle from the Cameron community carried wood to a fire pit, stacking it beside the cook pots and the camp fire where vegetables were chopped for mutton stew to feed the construction crew at noon.

Women came bearing watermelons for dessert, and men rolled up their sleeves and worked on the framing with hammers and levels in hand, balancing on wood rafters under the hot sun. The temporary community hummed with excitement.

At 10 in the morning ten people lifted the first wall upright under the clear blue sky. Applause erupted while Kerley and her three children watched from the shade of a golf umbrella.

“My children heard Mr. Phelps tell me he would get some people together from here to build us a new, safe house. When he left, my children said they didn’t believe him and I shouldn’t either because nothing good ever happens anyway.”

Although volunteer crews went back the next weekend to pour the concrete floor, install the electrical wiring, hang the three windows and a door and partially shingle the new roof on the one-room house, according to Phelps there is still more to do before the family can move out of their shack.

That first weekend, “we ran out of roofing,” but he was hopeful they’d get the last three squares needed and the dry-wall up before the weather turns cold out here. “I am confident we can do it. It is a new beginning.”

Skip Curley, president of the board of directors for Fort Defiance Housing Corporation, dba Sandstone Housing, a not-forprofit organization providing housing for Navajos, describes “substandard” as a culturally ambiguous term.

“Elders love their hogans, which lack amenities like flooring and plumbing. But the structures are culturally traditional and they prefer to live in them. They are,” in fact, very beautiful in their simplicity. “The elders are very comfortable in them.”

But he describes their grandchildren as the “other group,” the younger generation with a higher, urban standard of living. They expect to drive new pick-ups and live in homes with amenities their grandparents never dreamed of.

He added that modern reservation families find it difficult to get a loan on trust land, “so they get their home-site lease and then build out themselves.”

Sandstone Housing’s loan program is federally subsidized because loans from the private sector are non-existent. “You cannot collateralize trust land.”

The federal government developed construction guidelines to support the subsidized loan programs.

“On the reservation the guidelines include a construction engineer to oversee the code,” said Curley. “But traditionalism plays into the code, too. When I worked for pueblo housing, the federal government wouldn’t let them build with adobe even though the buildings there had been standing for hundreds of years.”

After years of debate, “they finally compromised. Pueblos would have to put rebar in the adobe to help keep it from falling down.”

HUD interactive maps show 2009 statistics for low-income households in Coconino County, where Kerley lives, as typical of all the counties in the Navajo reservation: 10,125 (76 percent) are low-income houses. Of those, 945 are substandard units; 960 are overcrowded, 5,780 are cost-burden units (paying more than 30 percent gross income towards housing costs.)

Homes lacking complete kitchen or plumbing facilities are the most severe housing problem, followed by overcrowding, followed by cost-burden. But if a household has more than one of these problems it is counted with the most severe problem.

Progress on Kurley’s new one-room home continued during the next eight weeks. The roofing was donated, a new outhouse built. And when electricity and water arrive Kerley’s house is ready with wiring and plumbing.

The doors and windows are thermal panes and located where she is protected from the frigid wind coming down Gray Mountain.

Early in November, Phelps sent out a succinct e-mail: “During the past couple of months we had the privilege to help build a small but safe dwelling for Marlene Kerley in Cameron.

“Marlene had been living in a ‘shack’ with her three children, but through the generous donations of many individuals with caring hearts and the skilled labor of many others, she will be spending this winter in the newly completed home. She has invited us all to attend her house warming on November 13. . .”

The housewarming was a celebration. The Kerley family even has a few new furnishings. Her home is secure, the roof won’t leak and the stove’s warmth will spread evenly through the one room they now call home.

She hopes to add on some day, but in the meantime she is convinced that her life is turned around.

“This changed my children. It changed my family. Now they will believe. I prayed and prayed for help. I think an angel brought everyone to us.”