|

Related story |

This is the second part of a two-part series. The first installment was published in March.

In mid-April, a Cortez man moved into a new apartment. He furnished it simply: a bed, a few chairs and a table, a TV, a couple of lamps. It was an unremarkable event except for one thing: he had been homeless for more than four years.

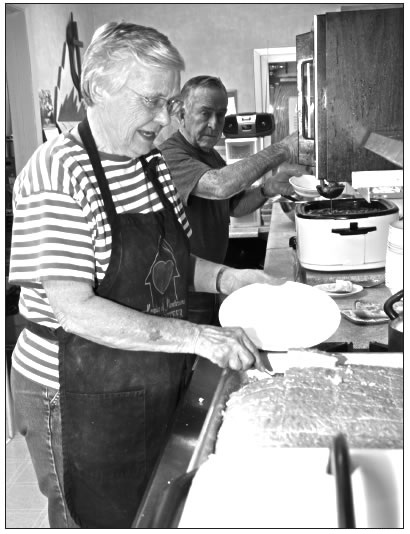

Christine and Jerry Chadwick of Dolores, members of the Johnson Memorial Methodist Church, provide a free lunch to all comers April 27 at the First United Methodist Church in Cortez. The Methodists provide lunches three days a week for street people, alternating with St. Barnabas Episcopal Church. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

“When his last marriage ended, he just dropped out,” said John Van Cleve, manager of the Bridge Emergency Shelter, where the man had been a frequent client.

For some time, “Brian” (not his real name), a Navy veteran who served during Vietnam, was one of Cortez’s street people. During winters he spent his nights at the Bridge shelter and his days in public buildings such as the library. In summer months, when the Bridge is closed, he stayed in an abandoned car.

“That’s how he lived for a long time,” Van Cleve said.

One night at the shelter, Brian approached Van Cleve about getting assistance. Van Cleve found out he was eligible for an old-age pension, “and we started working from there.”

“We had to get his papers,” Van Cleve said. “Homeless people tend to lose all their birth certificates, Social Security cards, driver’s licenses, things like that.”

But with Van Cleve’s help, Brian was able to obtain his pension, along with health care from the Veterans Administration and subsidized housing through the Housing Authority of Montezuma County.

“It’s pretty tough getting subsidized housing. There’s a long waiting list,” Van Cleve said. “But we found a landlord who was willing to work with us.”

Now Brian has a home.

“It’s nothing wonderful,” Van Cleve said. “He doesn’t have a car or a phone or cable. But he has everything he needs. It’s amazing how many people have stepped in and given him stuff. It’s really nice to see how happy he is.”

Brian represents one of the successes in the ongoing efforts of shelter workers and others to get people off the streets of Cortez and into better living situations.

Such successes come slowly, however. The people who hang out in the city’s parks and along its byways — some of whom are genuinely homeless, some of whom have families but aren’t welcome at home for various reasons — are a very diverse group with different needs and problems.

Brian was not a chronic drinker, just someone who had dropped out of society under the crush of too many stresses. But many other street people do have substance-abuse problems, primarily with alcohol. Others have one form or another of mental illness. Some simply can’t deal with authority figures and thus can’t hold a job.

Most spend some time at the Bridge Shelter, which since 2006 has operated out of the Justice Building at the corner of Mildred and Empire. What they get is a warm meal and a bed; the shelter is not open during daylight hours, and there are no medical personnel on hand and no paid counselors.

Shelter workers, however, are not shy about badgering the clientele to quit drinking (if that is their problem) and to seek help. And, once in a while, the nagging works — or people just decide on their own to change.

Another of the shelter’s long-term clients, “Leonard,” is a bright, talented man who used to own his own business. “If you met him on the street you’d have no idea he was homeless,” Van Cleve said. “But he had a problem with binge drinking.”

Recently, however, Leonard found a job, started going to Alcoholics Anonymous and “cleaned up his act,” Van Cleve said. Now he has his own apartment and is reportedly doing well.

Another shelter client, a good-natured, likable man with a powerful alcohol addiction, was persuaded this winter to enter treatment at Peaceful Spirit Alcohol Rehab Center in Ignacio, Colo. Another client is headed to a treatment facility in Gallup, N.M. And yet another has been trying to stay sober and has been reunited with his family on the Navajo reservation.

“We’ve had five or six clients that we’ve been able, with a lot of help from different people, to move out of the homeless situation and into something different,” said Van Cleve.

“But you can’t do that for everybody. There has to be some desire on the part of the person to change. We’re not thinking we’re going to cure everybody, but if we can help a handful, that’s good.”

Tolerance varies

Homeless people and transients have existed as long as civilization itself. Many cultures revered traveling priests and monks who lived off the charity of others. The Depression era had its hobos and rail-riders; big cities worldwide have always had beggars and panhandlers.

In Cortez, the number of chronic street people — those who hang out in public, sometimes drinking, sometimes not — is probably around two dozen, according to Police Chief Roy Lane. It isn’t their number that prompts concern, but the problems they cause. Those who drink get into fights with each other, stagger into roads, trespass on private property, pass out in parks, occasionally shoplift and annoy ordinary citizens. In the view of some people, they harm the city’s image. They also are at risk of dying on cold nights.

In April 2008, just after the shelter closed for the season, a man named Wendell Harris died of exposure in Cortez. Last February, Herman Scott, another shelter client, froze to death in Parque de Vida after refusing assistance from the police.

Street people can also be a concern because they don’t get regular health care and are perceived, at least, as being likely to carry germs they could spread in parks and libraries. Scott had a serious case of MRSA, the dangerous antibiotic-resistant staph infection, and was reportedly supposed to go to the Northern Navajo Medical Center in Shiprock, N.M., the day he died.

Tolerance for street people varies from town to town and from person to person. The homeless have strong advocates as well as vocal critics. Municipal officials everywhere struggle to balance compassion with common sense and the need for orderly streets with the civil rights of the down-and-out.

Cortez, like other towns bordering Indian reservations, faces the additional problem of those Native Americans who come into the city to drink because they aren’t allowed to on the reservation. Both the Navajo Nation and the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation are “dry.” Thus, Indians who do drink in Cortez tend to do it in the open and are more visible than Caucasian alcoholics drinking in their homes. And perhaps because of their visibility, there seems to be more concern about their drunken misdemeanors than there is about, say, drunks shooting up road signs or smashing mailboxes, a common occurrence in Montezuma County.

While some people favor a get-tough policy toward substance abusers, in effect telling them to “snap out of it,” liberals tend to see “getting them into treatment” as the answer. However, that is far easier said than done.

The Bridge shelter is a stopgap measure that gets people off the street at night. It is sometimes criticized as coddling alcoholics and enabling them to continue leading dissolute lifestyles. However, the picture is more complex than that, says M.B. McAfee, chair of the Bridge board and one of the prime movers behind its creation.

“In one sense, yes, the shelter is enabling them because we don’t have any way to do any follow-up after they leave in the morning when they’re relatively sober,” she said.

“Or you can look at our mission statement, which is simply to keep people from dying. In that regard we’re doing what we said we would do and we’re doing it really well.”

And the fact that the homeless and alcoholics have a place to go where people care about their welfare could help push them toward changing their lifestyle by boosting their self-esteem.

Listerine and hair spray

But changing is not easy and generally requires far more support than can be offered during overnight stays at a shelter. Many in Montezuma County have called for an actual detox facility that would be able to keep people for several days until they are genuinely sober and able to think about entering long-term rehabilitation.

“The bottom line is, any decision to do something about detoxing is an individual decision, and for our core of drunk people, the pull of the bottle is far stronger than the pull to get sober,” McAfee said. “All detox will do is give them an opportunity.

“There are maybe a few of our chronic drunk folks who would go to detox and might even go to rehab, but generally that’s not going to change the look of the people in the park. We’re still going to have drunks in the park.”

That’s something that many citizens find unacceptable, and officials struggle to find solutions.

After concern was raised at a Cortez City Council meeting this winter about drunks hanging around Mama Ree’s restaurant across from City Market, the city took letters to liquor-dealing establishments reminding them not to sell to intoxicated people, and the city offered a “refresher course” about liquor laws.

Some cities, including Farmington, N.M., and Seattle, Wash., have banned certain types of alcoholic beverages such as cheap “fortified” (high-alcohol) wines favored by street drunks. However, McAfee noted that just keeping alcohol away from alcoholics — even when it can be done — doesn’t mean they won’t get intoxicated.

“When they can’t buy liquor, they’ll get Listerine and hair spray, which causes diarrhea and incontinence, so we’re getting messier clients,” she said.

Other solutions involve trying to get people to go somewhere else. The city of Cortez removed a couple of benches on Main Street in front of City Market because they had become popular places for street people to hang out.

And the police have been diligent about discouraging people from drinking in public places. “They’ve been giving out citations for trespass and open container,” said Van Cleve.

But taking people to jail on minor offenses just to keep them off the streets is costly. Last year, according to Chief Lane, the police department spent more than $40,000 to incarcerate people for offenses related to substance abuse and loitering in the parks. In general, area law officers have welcomed the Bridge as an alternative to detention. Both Montezuma County Sheriff Gerald Wallace and Lane are members of the shelter board.

For the Bridge to evolve into an actual detox, it would first have to have a building where it could operate 24/7 year-round. Currently the clients must exit by 7 a.m. because the Justice Building is used for court purposes in the day. Then the facility would have to be staffed; at present there are one full-time and four part-time paid positions, and those are only seasonal. A caseworker position funded by the Ute Mountain Ute tribe is not yet filled.

‘A de facto detox’

The obstacles involved in getting street people to adopt a different lifestyle are enormous. Those who are alcoholics simply cannot get sober and stay sober without long-term treatment, and even then the odds of success are slim.

“Just detoxing them is not enough,” Van Cleve said. “We already have a de facto detox center. It’s the jail. They can be in there for months and as soon as they get out they get totally wasted. We need a comprehensive program. You aren’t going to get results unless you can motivate people to change.”

But for people to change, they have to see a real reason to do so, a hope of something better. For an alcoholic or drug addict to stay sober takes tremendous, unending effort. For an alcoholic street person with no job prospects and no support, there is no reason not to drink.

“I have seen clients who come in, and when they’re sober they’re the most depressed people you have ever seen,” Van Cleve said. “They have nothing in their lives, nothing to look forward to — no job, no house. They get a few drinks and they’re laughing and happy. They’re just trying to make themselves feel better, to have a place to sit in the sun and feel good.”

McAfee agrees. “People who turn to addictions are in a life that they perceive as too painful to deal with,” she said. “They’ll talk about the six people in their family who died in the last year, or losing their mother and their nephew within a few months, things like that.”

Even when someone is motivated to become sober, getting long-term inpatient treatment can be difficult. For Native Americans, there are several options in the Four Corners area. In addition to Peaceful Spirit on the Southern Ute reservation, there is a rehab facility in Gallup, N.M., and a new one being constructed in Shiprock, N.M. However, the logistics involved in getting into those facilities can be a problem. To get into the rehab in Gallup, for instance, clients must be at Shiprock’s Navajo Medical Center at 7 a.m. on one of three days a week and must be one of the first four people in line. Then they will be evaluated and possibly sent to Gallup.

For non-Indians on Colorado’s Western Slope, Grand Junction’s Colorado West Recovery Services and its Salvation Army center both offer residential treatment, but there is a waiting list at Salvation Army and CWRS costs more than $5,000. Outpatient counseling is available from several agencies in the Four Corners, but that is rarely sufficient for street alcoholics.

And treatment can be pricey for non- Native Americans. Most insurance companies that cover substance-abuse treatment pay no more than half the cost, which for a three-week program can be several thousand dollars.

If someone has both substanceabuse problems and mental-health issues, treatment is even more problematic. The state Mental Health Institute in Pueblo, Colo., offers a program for people with those dual challenges but the waiting list is so long, it can take months to get accepted.

Over-reacting?

McAfee recognizes that it can be difficult for sober people who are struggling to hold jobs and pay their bills to understand why street people who aren’t even working deserve much help. She said she visited a facility in Holbrook, Ariz., that she considers a model for how things could be done.

Holbrook, which is also a border town and is similar to Cortez in population and economy, has a shelter that offers an austere holding place for drunks, with mats on the floor and water and granola bars for fare. Across the street is a “dry” shelter that is also a transitional-housing facility. An adjoining woodworking shop offers part-time work for people at the shelter, who make desks and bunk beds sold locally. They pay a small amount for their keep and gradually learn job skills and responsibility.

McAfee would like to see something similar in Cortez.

Most cities large enough to have shelters do separate the intoxicated and the sober homeless. In Durango, there is a detox facility operated by the Southwest Colorado Mental Health Center and an alcohol-free homeless shelter run by Volunteers of America. People can stay for two weeks free at the homeless shelter; if they want to stay longer, they can apply for the transitional- living program and, if accepted, must pay nominal rent.

“If we could have a building, we could do a detox center and have a transitional-housing thing,” said McAfee, who envisions some sort of after-care for sober clients and a case manager who could teach people how to negotiate the system and obtain needed assistance from the VA, Medicaid, Medicare, and so on. “I think it would be a remarkable resource for our community and it’s something that is needed more and more as we’re plunging into the darker times.”

But the darker economic times mean that a capital campaign for a new building would be extremely difficult to mount at present.

Van Cleve says he understands why some citizens think the Bridge is too gentle with street people, but he doesn’t see much of an alternative.

“We do enable some people,” he said. “They know they can get drunk and come to the shelter and we’ll clean them up and put them to bed, and in the morning they run as fast as they can to where they have their bottles. It’s discouraging and hard, and we get tired of it.

“But I think my job as a conservative citizen is to try to keep these guys alive, not make their problems worse.

“I see folks come in and they’re very beat up. What does that say about our community?

“I really feel like we’re over-reacting to these folks in some ways. They’re being thrown in jail to placate owners of businesses or folks that just want these people to disappear. I understand that people don’t want their customers harassed. and I don’t blame the police for doing their job.

“But the problem is, what are we going to do with these folks? Keep arresting them for what I consider to be minor offenses? Show them the edge of town? Or provide a facility of some sort?

“We have no place for these people to be. We have to figure out what is the most Christian way to deal with them that also addresses the problem, without hounding them and making their lives miserable.”