Peace and Justice marchers walk along Cortez’s Main Street in September 2020. Photo by Gail Binkly.

In January 2020, before the pandemic hit, Cortez made the national news because of controversy over what was being sold at a local retail outlet.

CNN, and later the New York Post and New York Daily News, reported on a local woman noticing replicas of old racist signs such as “Public Swimming Pool – White Only” being sold at a shop just outside the city. The owner said they were popular items.

In September of this year, Cortez made the national news again. “Political Divisions in Cortez, Colorado Got So Bitter the Mayor Needed a Mediator” read the headline on an article in the Wall Street Journal.

“. . . this community of 8,700 became racked by tensions over politics, race and Covid-19,” the WSJ stated, discussing conflicts between motorized parades by a group called the Montezuma County Patriots and silent sidewalk marches protesting the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police.

The WSJ noted that some Patriots had more recently turned their attention to school-board meetings, where they “have railed against mask and vaccine mandates and teaching critical race theory in schools. . . . [The Montezuma-Cortez Re-1 school board] recently passed a resolution opposing critical race theory, which argues that America is historically and structurally skewed toward white people.”

Then, late in November, the Washington Post Magazine published an article by Austin Cope, a writer from Cortez, about the February 2021 recall of a member of the Re-1 school board, Lance McDaniel, over progressive posts he made on Facebook. The article did not focus on race, but it noted that the school board – which serves a district that is roughly half White, one quarter Latino, and a quarter Native American – is all White, and that many of McDaniel’s critics were Patriots.

It seems that Cortez and Montezuma County are being branded with the stigma of a racially insensitive place.

Is the bad reputation justified?

Locals say the answer is complex.

Sidestepping

“This area has its share of racism. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t ever experience it,” said Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk, a member of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe who works as cross-cultural programs manager for the Montezuma Land Conservancy. She said she has lived in the county all but some 15 years of her life, and attended school in the Re-1 district.

She served on the school board from 2018 to 2019.

Lopez-Whiteskunk said the local political climate has grown increasingly hostile of late. “It seems like what we’ve tolerated and lived with over the years is becoming more blatant and in-your-face,” she told the Four Corners Free Press by phone. She cited the Patriots’ parades as an example.

“Many of us choose not to go into Cortez on Saturday at that time in the morning,” she said. “We do our best to sidestep it.”

She said the Four Corners, especially Southwest Colorado, has long been viewed as a somewhat backward area. “When I served on the school board, the first time I attended a statewide function of school-board members, I introduced myself and people said, ‘What’s it like to live there? How did you manage all those years?’

“And they’re right. It’s here. It’s just how we’re taught to deal with it. You identify people who align with you, your activities, your beliefs, and sidestep those that don’t. It’s how many of us have managed to navigate.”

Whiteskunk mentioned a function that took place on Oct. 10, 2020, at the Cortez Cultural Center’s outdoor plaza in honor of Indigenous Peoples Day. There were a number of Native speakers, including her. Members of the Montezuma County Patriots were invited to attend and some did, watching the speeches.

However, some Whites stood at the entrance to the plaza, displaying guns and making negative remarks.

“They were being a little pushy and a little scary. It wasn’t a friendly environment,” Lopez-Whiteskunk said. “One lady had her flag on a pole and she waved her flag in my face. I said, ‘I’m here because I was invited to speak.’ I felt my personal space was being invaded.”

She said many Natives are highly patriotic.

“My grandmother was a big supporter of the veterans, the VFW, and the Ladies Auxiliary in her community. My grandmother was a patriot. She would display a flag outside her house. She lived in Utah and had a red-white-and-blue license plate.

“I’ve had uncles who served in the military. We had one family member who didn’t return because he came upon explosives and came back in parts. It was hard watching this really strange twist of those values and it really made me think about what my values are and why.

“I had a hard time trying to see through the lens of those individuals that run the parade. What’s the point you’re trying to make? It seems to be freedom to display your weapons or wear a mask. The freedom I know of is to go where you want to within our country – men and women giving their lives to protect that.

“For generations Native Americans served in the military even when we weren’t recognized as citizens of this country.”

‘Least racist’

Lopez-Whiteskunk, a former co-chair for the Bears Ears Intertribal Coalition, which worked to secure the creation of Bears Ears National Monument in San Juan County, Utah, said that area also has some residents with biases and prejudices.

“You get the same sort of sentiment in Southeast Utah,” Lopez-Whiteskunk said. “I have no problem going into Bluff. When I go to Blanding and Monticello, I have to be careful.”

Ed Singer, Diné (Navajo), a painter who divides his time between Cortez and his home in Gray Mountain, Ariz., said he doesn’t believe Cortez is especially racist.

“I think it’s the least racist of all the border towns,” he said over lunch at Once Upon a Sandwich in downtown Cortez. “The closest to where I grew up was Flagstaff, and it’s easily 10 times worse.”

He mentioned an incident in Flagstaff when he was working to repair a vehicle and needed an auto part. He jumped into his other car to go into town.

He stopped to buy a cup of coffee at a coffee shop and the barista asked him in a hostile way, “What do YOU want?”

“I said, ‘Coffee – isn’t that what you sell here?’ I was treated horribly,” Singer recalled.

Another time he was refused service at a restaurant in Flagstaff and accused of being drunk when he was not, he said.

He hasn’t found Cortez to be as hostile, but he said he found it odd one time when he was sitting in the parking lot at a local gas station, reading an instruction manual, and a local schoolbus pulled into the lot, cut a little too close to him accidentally and struck his truck a glancing blow. The driver went into the convenience store for a coffee and Singer followed, telling him he’d hit his truck.

The police who responded were oddly skeptical, Singer said, saying the bus could not possibly have hit his truck because the bus’s bumper was too high. Singer said the bus had gone into a dip and then went up and down, striking the truck and causing visible damage. The officer said if Singer pursued this he would be arrested for filing a false report, Singer said. So he decided just to take the loss.

As a painter, he has studio space on Cortez’s Main Street that gives him a “front-row seat” through the window for the Saturday morning parades. “I thought it was pretty insane,” he said. “There were a lot of Trump and Confederate flags. I could see the merchants – which ones were supporters – they came out waving flags as well.”

Many cycles

Both Lopez-Whiteskunk and Singer said that the outrage and shock over the death of George Floyd was difficult for Native people to completely share because they are accustomed to injustice and bad treatment.

“In the Native community, it’s just another of many cycles,” Singer said. “The American Indian Movement was born in Minnesota at the time of the civil-rights movement as a result of the racism in Minnesota, so it’s not really a surprise that George Floyd got killed there. Natives used to have patrols to protect Native people and Native lives in certain parts of the Minnesota community where more Natives were in the population.”

Lopez-Whiteskunk echoed that feeling. “The fact that one incident could be propelled to mass-media coverage of national proportions, it’s hard for me to process,” she said. “I don’t know about other indigenous people throughout the country but that happens on our reservations all the time. It goes undocumented. This is the justice system we’ve been dealt with for generations.”

She noted that White people often brag about how long their families have been in the area, such as saying they’re “fourth-generation.”

“Indigenous people have been on these lands for eons, long before any colonizers showed up,” she said. “Our sense of time is tied to our origin stories.”

Basic character

Allen and Valerie Maez, who live in Lewis north of Cortez, acknowledge that wrongs were done to Native Americans, but don’t believe people of the past should be judged by modern standards.

Allen Maez is the chairman of the Montezuma County GOP, while his wife, Valerie, writes a conservative column in the Four Corners Free Press. They can frequently be found at Conservative Grounds, a hangout on Cortez’s Main Street for those on the right end of the political spectrum.

“I think it’s dangerous to put 2020 thinking into the 1820s,” Valerie said. “Were there atrocities? Sure. Some of the stories are bone-chilling.

“But it comes down to the times you live in. There are things that were acceptable once that aren’t now and you don’t want them to be. It comes back to your basic character. Who are you as a person?”

Allen said his family came into the area because the government was allowing people to homestead. “The lands were not occupied,” he said. “The Natives would ride back and forth hunting.

“My folks got along just fine with Native families.”

His family was “one of the only, if not the only, Hispanic families in Lewis,” he said. “One man asked me, ‘How can a Hispanic have so much land?’ and I said, ‘Because we have a work ethic.’”

Both Allen and Valerie Maez said they don’t believe racial divides are worse in this area than in other areas they have seen.

The United States is “on track to become a pretty integrated society,” Valerie said. “But I think some, not all, of the Black Lives Matter movement set us back. Pulling down statues, burning things down – nobody has any respect for that. Martin Luther King said you judge people by their character, not the color of their skin.”

Allen said there is bias in the local area, but not necessarily racism. “You can go anywhere and people will have a bias. It may not be because of color. It may be because they’re from ‘over there.’ Country kids vs. city kids. Poor people vs. people that have a bit more.”

The Maezes have not closely followed recent cases, such as the trial and acquittal of Kyle Rittenhouse on charges of murder for shooting BLM protesters in Kenosha, Wis. “Right now there’s so much information and trying to make things racist,” Allen said. “That’s why we don’t have TV. We try to read our news.”

“We’re probably in the 1 percent of Americans that don’t have TV,” Valerie concurred. She said she doesn’t think conflicts are as much about racism as people’s characters. “There are always people who are swine, and there’s not too much you can do about it. There are those people. They cross ethnic lines and nationalities.”

Valerie said she is not closely involved with the Patriots, but she is acquainted with some of them and believes they have been treated unfairly and harassed more than people realize.

‘Offensive’

The anger and divisions triggered by the Peace and Justice marches and the rides by the Montezuma County Patriots linger in the community. The Patriots are still making motorized appearances on Saturdays, though the Peace and Justice people ceased their marches after a year.

Cortez Mayor Mike Lavey and his wife, Gail, shown here in the Carpenter Natural Area. The mayor worries that the divides in Cortez are harming local businesses. Photo by Gail Binkly.

Cortez Mayor Mike Lavey, who was interviewed by the Denver Post and Wall Street Journal about the conflicts, said the Patriots seemed to have had an exaggerated response to the marches. He said he could understand people being upset about the burning and looting that occurred in other places, but nothing like that was happening in Cortez. Yet people carrying Black Lives Matter signs seemed to outrage the Patriots.

“They couldn’t see any difference between looters and burners, and people silently walking on the streets,” Lavey said.

Sherry Simmons, one of the organizers of the Patriot rallies, wrote in the Cortez Chronicles, a recently started online site offering conservative opinions and news, that the local BLM demonstrators were offensive to many people.

“The Black Lives Matter Movement began in June of 2020,” Simmons wrote. “It first began with protest on Montezuma Avenue. The Patriots ride began in April of 2020. Their paths crossed when the BLM protesters changed their venue to Main Street. It was shortly after this when dissent was visual. BLM carrying signs supporting such things as defunding the police, and posters stating ‘End White Supremacy,’ were something Cortez had not seen before.

“Cortez has always been a quiet little town in rural Colorado where racism seemed far off, where the community comes together for any need and for anyone, with no skin tone attached,” Simmons wrote. “It is part of a community where neighbors help neighbors, with children playing with other children and with people coming together for what ever need that may arise. The BLM protesters were offensive to many, some feeling personally insulted for they understood that they did not base anything on skin color. This is a community who honored Almighty God, Law Enforcement, our Veterans and America. Somewhere in the midst of the BLM protesting, a hate emerged for the American Flag and anyone who flew it.”

Simmons also wrote that people have cursed at the Patriots, thrown objects at them, and vandalized their cars and flags.

However, the only known incidents in which a group of people physically menaced demonstrators seemed to be directed at the BLM/Peace and Justice marchers. One incident on Jan. 2, 2021, resulted in harassment charges against six people. (July 2021 Free Press)

Racist image?

The flag issue that caused the most division, did not involve American flags but Confederate ones. Numerous participants in the Patriot rides, particularly in 2020, carried these symbols that date from the Civil War.

“They say it’s part of our history, but I’d say it’s an overt racist image,” Lavey said. “They’re doing it for the shock appeal. Some had flags that said ‘Fuck your feelings’ and ‘All Democrats are traitors.’ Some of the Patriot leaders invited council members to attend their meetings, but when they’re flying flags like that, why would I want to give them credibility?”

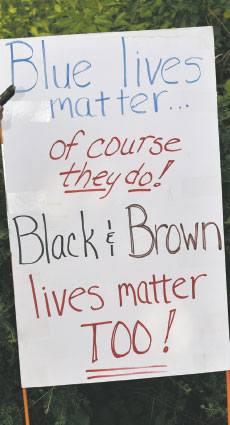

A sign at one of Cortez’s many demonstrations.

Allen Maez said the Southern flag was not meant in a racist way. “It was an expression for them, their rebellion,” he said. “Those folks felt that we have to rebel, and the Stars and Bars was something they saw as a symbol of rebelling against the attempts to take away freedom. It didn’t have anything to do with slavery. It was a symbol of ‘we have to fight for our freedom.’”

Valerie Maez added, “Most of the people around here have memories of Dukes of Hazzard [a TV show set in Georgia that often featured the Confederate flag]. It meant driving fast and beating the law. I don’t think people flying the Confederate flag is so much about defending slavery but about defending lost rights and freedom.”

The Confederate flag figured in an incident more than 16 years ago that prompted a meeting of the Colorado Civil Rights Commission in Cortez. On June 21, 2004, some visiting college students from Dillard University in Louisiana and the University of Colorado at Boulder were allegedly menaced by young local White men in a pickup flying the flag.

Then-Police Chief Roy Lane (who is now deceased) told the Free Press at the time that there may have been mutual name-calling between the groups, but the local teens then used their pickup to block the sidewalk in front of the guests.

“Were those kids [the visitors] scared? You bet they were and I don’t blame them,” Lane said.

Police broke up the incident and there was no violence. Lane said he thought any racial problems in the local area were caused by the actions of a very few people.

‘Kind of beautiful’

Dawn Robertson, who helped organize the Peace and Justice demonstrations, told the Free Press that she can’t say exactly what the message of the Patriot parades is.

“I think the amount of hysteria, vitriol and contempt that was shown against grandmothers holding up a love sign is pretty indicative of the energy here, the energy and the intention,” Robertson said. “Was it racism? I can’t say what the intention is in someone’s mind.”

The Montezuma County Patriots drive along Main Street in Cortez on a Saturday morning in 2020. Photo by Gail Binkly.

Robertson, who comes from a rural town north of Boston, has traveled extensively in Europe as well as to Turkey, Egypt, and Mexico. As an AmeriCorps volunteer, she moved to Cortez from California as the demonstrations were beginning.

Her critics have labeled her an outside agitator looking to foment trouble, but it was reportedly Sylvia Clahchischilli, Diné (Navajo), who began the marches. Robertson and several other people took over after Clahchiscilli stepped aside because of concerns about COVID.

Robertson identifies herself as mixed-race, with an African-American father and a White (Scottish and English) mother. She has a degree in history.

She has not been closely involved in political activity of late, but is working as marketing coordinator for the Southwest Farm Fresh Cooperative in Cortez.

Robertson said she has never been any place during her extensive travels where racism doesn’t exist. However, in Europe the countries are so small and there is such a variety of cultures that “plurality is understood,” she said.

“In a general sense, everyone’s been on top and on the bottom in Europe at some point so there’s a more mature approach to nationalism, although this is a huge generalization on my part. Germany has been at the top and then at the bottom – they all have. People with a healthy heart and mind are capable of thinking, ‘Being Greek is amazing but I don’t have to be the best at everything.’”

But, though things are somewhat different in the United States, she has praise for this country. “I think it’s kind of beautiful that the United States is holding itself to a standard that is higher than where it’s at now. The United States is unique.”

She said she feels she is even more patriotic than some locals because “I’ve been abroad and I came back.”

Ascertaining whether someone’s behavior is racist is difficult because there is no agreed-upon definition of racism. “People who study diversity have said racism inherently comes from the people in power, and use the term ‘bias’ for others,” she said.

In the demonstrations she organized, participants were told to be silent. “I started every walk with a talk about how ‘this is the service you are going to do for marginalized people, allowing that hate to roll over you.’”

The one time a participant in a march ran into the street and tried to pull a Patriot off a motorcycle, he was publicly dismissed and never allowed to take part in another Peace and Justice walk, she noted.

She said she reached out to the Patriots’ organizers but they refused to talk with her, though they were willing to talk to other, White march organizers. “Is that racism? I think calling someone a racist is a nonstarter,” Robertson said.

After one walk, she said, someone followed her around town with a Confederate flag, “a flag that symbolizes slavery.”

“I don’t think it’s a stretch to say it’s ill will and intimidation.”

On the alert

The message of those flags has raised questions in a number of people, including Montezuma County Sheriff Steve Nowlin. “I don’t even think those that had them knew what the heck they meant,” he said.

Nowlin, who has spent 45 years as a peace officer and seven years as the county’s sheriff, told the Free Press the sheriff’s office has not seen many incidents that involved racial disputes. “We have so many different cultures, and so many people are of mixed cultures,” he said. “We always are on the alert for any type of racial situations.”

Recently, he said, some signs were put up in front of a former business with “some very racial slang words,” Nowlin said.

“That is a crime. We shut that down right away and educated that individual, and so far there has been nothing else there.

“Freedom of speech is fine if it’s not a violation of a person’s civil or constitutional rights.”

Nowlin said local law officers have frequent cultural and anti-bias trainings.

“We just don’t see it [racist activity] here. I know it exists in certain places. I don’t condone any of it. I have a good relationship with Southern Utes, Ute Mountain Utes, Navajos, and Hispanics. I have a lot of friends of many different races.” (He noted that there are not many Black people in Montezuma County. According to U.S. Census figures, the Black population here is just 0.5 percent.)

But Nowlin said there certainly are people in this community with biases, and prejudice can be held by people of any race.

After the killing of George Floyd, Nowlin said, he identified several people coming to local vigils who were outsiders associated with the Antifa movement. “I stepped in,” he said. “I said, ‘Your mask doesn’t hide who you are.’ It was just me explaining this is not a racial-bias community. There are people who have those biases or prejudices but they are not allowed to do things that would be unlawful. You can draw a line in the sand and make sure they don’t cross it.”

Nowlin said people should learn their history. “I can’t change Manifest Destiny or the treatment of indigenous people – I wasn’t there,” he said. “We can’t change the past but we can learn from it and prevent the bad things from happening again. History does matter.”

He says he has a calendar with historical photos, one of which particularly affects him. It shows a group of Utes surrounded by Western-attired people. “The looks on the Utes’ faces told the story,” he said. “I can just see the pain. It was the end of an era.”

But he is hopeful about the future. “I’m in schools all the time. The younger generation – they really get along and I think that’s maybe a seed for hope.”

White pride

Robertson shared Nowlin’s sentiments about learning history. Despite the fact that that was her major, until a year ago she knew nothing about Native American children being dragged to boarding schools and frequently abused, she said.

“There are many reasons why Native Americans would not like the 2020 protests or feel affinity with them,” she said. “Non-Native Americans need to wake up.”

But Native Americans have something that Black African-Americans do not, she said – a tie to the land. Blacks were brought here as chattel. Even after they were finally released, they weren’t welcomed into the society.

Native Americans – those that were left after tribes were decimated – still have an identity and roots they can draw from, she said. “Which is healthy. But Black America always has to assert stuff vs. White America because there was no Black America first.”

Robertson said she thinks White people are struggling to find a way to maintain pride in their heritage. “They are trying to cling to a White pride that is clean, and they don’t know how to do it. I think it’s important to have some White pride. It’s a core part of a healthy ego to have an identity.”

‘All the same’

Despite the conflicts and divisions, most of the people interviewed expressed cautious optimism about the future.

“I think cell phones with video cameras may be the end of racism,” said Singer.

Many people who come into Conservative Grounds are not White but of other races, Valerie Maez said. “It gives me great hope that we can reach people. Maybe we’ll come together.”

Lopez-Whiteskunk said all human beings have much in common.

“At the end of the day, we are all the same. We walk on Mother Earth, we drink water, we breathe air. It’s an honor to be able to do that, especially in this place where we have open space and such a beautiful location. There’s so much to be grateful for. It’s useless to spend your time being angry and ungrateful.”