Is the new management plan for Canyons of the Ancients National Monument skewed toward preservation to the detriment of energy exploration?

The Montezuma County commissioners believe so, and they have led a charge to protest the plan in a lastditch appeal to have portions of it changed.

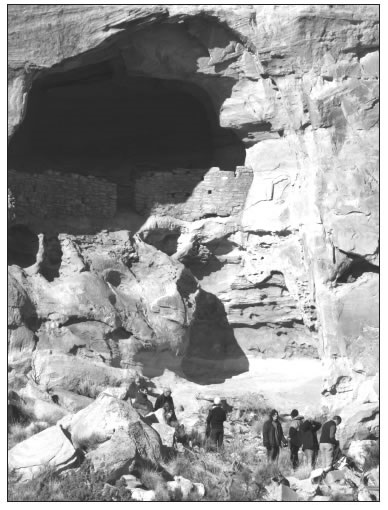

Hikers visit one of the signature Ancestral Puebloan sites in East Rock Canyon in Canyons of the Ancients National Monument. Photo by Wendy Mimiaga

Their efforts have been supported by the Dolores County commissioners, the city of Cortez, Empire Electric Association, the Montezuma Community Economic Development Association and the Cortez Area Chamber of Commerce, as well as Gov. Bill Ritter, state Sen. Bruce Whitehead, and state representatives Ellen Roberts and Scott Tipton.

According to a paper prepared by Montezuma County, problems with the proposed plan include that it “does not provide for multiple use” and “is not honest about how restrictive it is.”

The energy companies Kinder Morgan, Bill Barrett, Questar and Bayless have written letters officially protesting the proposed plan.

But officials with the BLM, which manages the monument, believe the plan is a reasonable effort to balance the many uses occurring on the monument, which contains the highest density of archaeological sites in the country as well as one of the nation’s richest sources of carbon dioxide, the McElmo Dome field. CO2 is used to help extract oil from wells.

“When people think of multiple use, they need to remember that doesn’t mean every use on every acre,” said Bill Dunkelberger, BLM San Juan Public Lands associate manager, “especially in a national monument which has a special management directive in a proclamation from the president that protects certain values and elevates them over others.”

The struggle between Montezuma County and the BLM over the monument is a long-standing one.

The 165,000-acre monument was designated in 2000 by President Bill Clinton after local residents shot down efforts to have the area protected as a National Conservation Area under special legislation.

The monument designation was unpopular among many locals, who worried that it would mean a curtailment of traditional activities such as cattle-grazing and energy development. A few fading “No National Monument” billboards still stand defiantly along roads around the county.

However, the tourism industry and conservationists welcomed the designation as a way to protect irreplaceable Ancestral Puebloan sites.

Balancing act

The monument functioned throughout the 2000s without an official management plan. After more than five years of work, the BLM released a draft plan in October 2007; the Montezuma County commissioners at that time submitted concerns about what they saw as a squeezing out of grazing and energy development, and the loss of some historic access to private inholdings.

The actual proposed plan, with some revisions in response to comments, was released on July 31, 2009. A protest period for the filing of formal objections closed this fall. The BLM’s national office had not responded to the protests as of press time.

Although past commissioners have been critical of the monument, the current board — Larrie Rule, Steve Chappell, and Gerald Koppenhafer — has been especially so.

Chappell and Koppenhafer expressed their frustration at a meeting in August 2008, at which time they told Monument Manager LouAnn Jacobson and other officials that the BLM was creating unreasonable delays for energy projects.

“Everything everybody was worried about when they created this monument is coming true,” Koppenhafer said then.

Balancing the different interests involved in Canyons of the Ancients has always been difficult. The proclamation creating the monument states that it “shall remain open to oil and gas leasing and development; provided, the Secretary of the Interior shall manage the development, subject to valid existing rights, so as not to create any new impacts that interfere with the proper care and management of the objects protected by this proclamation. . .”

The commissioners believe the phrase “subject to valid existing rights” means that traditional uses should have equal standing with archaeological protection, but the BLM’s position is that activities such as energy production can occur only if they don’t affect the resources.

After the release of the proposed plan in July 2009, the commissioners set to work soliciting support for their appeal, even sending out sample letters for sympathizers to to use when writing the BLM or elected officials.

They received numerous responses.

In an Oct. 26, 2009 letter to Sen. Mark Udall, the Cortez City Council wrote, “As a small southwestern municipality, the importance of continuing the longstanding multiple-use management strategy on public lands is vital to the diversity of our local economy. . . .We are very concerned that the proposed [plan] does not honor the [presidential] Proclamation language. . . and fails to give full effect to valid existing rights. . .”

Cortez City Manager Jay Harrington said the letter had been reviewed by the council during a work session and was signed by Mayor Orly Lucero. He said it was not a formal action and no vote was taken.

“There was a bit of talk of the overall importance of Kinder Morgan and the CO2 production to the entire community,” Harrington said. “But they were also sensitive to the value of archaeology and tourism.”

Empire Electric also weighed in on the county’s side, sending a letter to Sen. Michael Bennett that noted that Kinder Morgan is “Empire’s single largest customer accounting for almost [one-half] of Empire’s total annual revenue” and stating that the “importance of multiple-use to our small western Colorado communities and to Empire’s 15,700 active customers simply cannot be overstated.”

“We have been informed that the proposed [plan] imposes new restrictions on energy production that will severely curtail or even completely prohibit future energy development,” wrote General Manager Neal Stephens for the electric co-op. “We simply ask the BLM to strike a reasonable balance between [multiple uses and cultural protection] as we believe the Proclamation directs.”

‘Reasonable access’

The Montezuma County commissioners and Kinder Morgan, the major CO2 operator on the monument, organized a meeting and a tour on Dec. 15 to discuss some of the concerns. The meeting, which was not announced to the public, included Commissioner Gerald Koppenhafer, aides with the offices of Colorado’s two senators and with Rep. John Salazar’s office, the monument’s Jacobson, San Juan Public Lands Center Director Mark Stiles, and a few energy-company officials. (The meeting did not include a quorum of any governmental body, so it was in compliance with state sunshine laws.)

Jacobson reportedly presented facts about drilling and grazing, and Bob Clayton, operations superintendent for Kinder Morgan, showed the attendees a couple of drilling sites.

James Dietrich, the county’s federallands coordinator, went on the tour and said CO2 production is “really a top-notch operation.”

He said the county’s position had not changed as a result of anything said in the meeting.

“I would say the commissioners’ position remains the same,” he said. “Basically what we’re after is having reasonable access to oil and gas deposits.

“We understand all the cultural resources are very valuable. Nobody wants to do anything that would harm any of the cultural values, but we feel there should be certain compromises.”

The density of cultural sites is so great, Dietrich said, it makes it difficult for energy production to occur. “It’s just carpeted with things out there. We just want the BLM to work with the oil and gas companies to come up with reasonable solutions.”

One of the county’s concerns, Dietrich said, is the push for more “directional drilling” — using one well pad to drill several wells at angles instead of having multiple wells that go straight down. “That may or may not work in all cases,” Dietrich said.

Although the county is primarily concerned about how the new plan will affect future projects, “We’re also worried about the way it’s working now,” he said. “They’re already holding the drilling companies to new standards.”

Both Kinder Morgan and Questar have met obstacles with recent proposals, Dietrich said. “It’s part of an overall pattern the county’s really worried about. The approval process has been slow — it’s taken years where it probably should have taken months.”

A Questar spokesman declined to comment on the matter.

Clayton said Kinder Morgan’s concerns — as expressed in its 43-page protest letter — include the plan’s classification of visual resources. The BLM has a Visual Resource Management system that classifies areas according to their scenic value. Class I areas can undergo only minimal changes to the landscape, while Class 4 areas are allowed to have activities that cause major changes.

“Most of the monument, although leased, is in VRM 2, which is very contradictory with oil and gas,” Clayton said. Most court decisions have said that drilling should occur only in VRM 3 or 4 areas, he said.

Another concern the company outlined in its protest is about the term “settlement clusters,” which was used in the plan to replace an earlier term, “cultural community,” which had prompted widespread criticism. However, Clayton doesn’t believe the new term alleviates his concerns.

“They’re pretty much stating they will deny any APDs [applications to drill] in these areas [of settlement clusters],” Clayton said. “Our concern is, we hold wells in there and it’s really outright denying the use of our lease.”

A proposal to drill seven wells on Burro Point is an example of how new policies have already affected Kinder Morgan, Clayton said. The company found an unexpectedly high density of archaeological sites there, and the proposal languished for years while the logistics of drilling were hashed out. “We did find some areas that were clear, but LouAnn [Jacobson] felt they were still too close [to sites],” he said. Now, the wells will be situated on three pads, and directional drilling will be done from there.

For 27 years, Kinder Morgan followed an established procedure to define the perimeter of a cultural site, Clayton said — not merely outlining surface walls or rubble mounds, but establishing an area where there is no evidence of cultural activity below ground, then moving 50 feet beyond that.

The new plan calls for drilling no closer than 100 meters to cultural sites. “That makes it almost impossible to find something that doesn’t infringe on something — it’s a cultural site surrounded by a football field,” he said.

The company also is concerned about rules limiting noise, he said. “We would like some exemption for the actual drilling.”

Clayton said Kinder Morgan has a good reputation and operates respectfully on the monument. “Once we’re done, everything is put back into native grass except for a little teardrop road around the wellhead,” he said.

Clayton said, as a longtime resident of Cortez, he wants to see energy production on the monument because it is critical to the county’s economic welfare. Energy production supplies nearly half the county’s property-tax revenues, and the largest portion of those revenues comes from Kinder Morgan. The biggest chunk of the tax revenues goes to school districts.

In allowing energy development within a national monument, Canyons of the Ancients is extremely rare. Clayton said this is “an opportunity for industry to really shine and show that this can be done responsibly.”

He said the letters of support from Ritter, Salazar, and the local entities are helping. “The heat’s really getting put on.”

A road map

Jacobson was on vacation and could not be reached for comment. However, Dunkelberger said the BLM works to balance all types of uses on the monument and to support “valid existing rights.” However, cultural-resource protection comes first, he said.

“The proclamation reinforced that the cultural-resource values are so significant, we have to mitigate the effects on those resources before we permit oil and gas, recreation, grazing or other uses,” he said.

“This is one of the few national monuments where oil and gas development is permitted. I’m not aware of any others.”

Approximately 85 percent of the monument is leased for energy development, according to information from the BLM, and there are 125 producing oil and gas wells (half of them for CO2, others for natural gas or oil). Since June 2000, 12 new drilling applications have been approved, as well as 20 permits for extending the life of existing wells.

Jimbo Buickerood, public-lands organizer with the nonprofit San Juan Citizens Alliance in Cortez, said his group supports the new plan. He called it “a balanced plan that is really true to the proclamation.”

“Multiple use will continue,” Buickerood said. “Hunting, grazing, bird-watching, fluid-minerals development all will continue. The average citizen’s not going to see a change. You’ll still be able to horseback-ride, travel on roads and trails, and view most archaeological sites.

“Most of the grazing areas are still open. And the plan is for all the fluidmineral rights, whether CO2 or natural gas, to be open for exploration, within the restriction of taking care of the cultural resources.”

Buickerood said the long-awaited plan will make things easier for everyone “by providing a road map of how to proceed, whether you’re an energy interest or you want to go rock-climbing or you have some private property and want to change your right of way.”

And although the plan has been a long time coming, he said, “By taking that much time, it’s probably going to be correct, legal and fair.”

BLM National Director Bob Abbey is expected to rule soon on the appeals after examining the issues raised in the protests, according to Dunkelberger. If the analysis is found to have been insufficient in regard to a significant issue, the plan could be remanded to the monument to be rewritten, a very rare occurrence. The plan can also be affirmed in its entirety, or affirmed with instructions to supplement certain parts of the analysis, he said. If it is affirmed, any further protests would have to be as court challenges.

For more information, see www.blm.gov/co/st/en/BLM_Programs/land_use_planning/rmp/canyons_of _the_ancients.html.