The young education coordinator introduces herself: “Hi, I’m Kelly.”

“Hi, Kelly,” shout first- through fifth-graders from the local Faith Christian Academy. They have come to the E-3 Children’s Museum in Farmington to learn about every kid’s favorite subject. Kelly Hile grins. “Who’s ready to see some baby dinosaurs?”

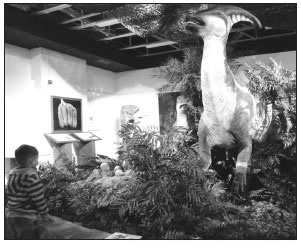

A young patron enjoys an exhibit in “Baby Dinosaurs: A Prehistoric Playground” at the E-3 Children’s Museum in Farmington, N.M.

“Me! Me!” Boys jump and clap. Girls thrust their hands high. Everyone looks beyond Kelly into a huge room holding the exhibit “Baby Dinosaurs: A Prehistoric Playground.” Roars, growls, and rumbles bounce off the concrete floor, reverberating into metal rafters.

“OK!” she shouts above the racket. “Before we go in, what’s a good rule for a museum visit?”

“Don’t touch the exhibits,” someone ventures.

Her grin broadens. “If you can’t touch it we put in a case so you can just look at it. You get to play with everything else and that’s a lot of fun.“

“Yeaaaay!” They dance.

She steps away from the exhibit entrance. The kids churn past her, teachers and parent chaperons straggling behind. She beckons me. “I love telling them they can touch.”

We walk into the Prehistoric Playground. It echoes with squeals of discovery. She points to a Stegosaurus puzzle. “Everything’s right at our knees, which is perfect for the little ones. We’re drawing a lot of parallels between dinosaur babies and human babies.”

A teenage volunteer dodges a maelstrom of boys and steers first-graders to stations where they can pop baby dinosaur puppets out of eggs, draw pictures, make rubbings, or use stencils and stamps.

“What those projects do for kids is help them learn fine motor skills, and grasping something, and making marks in a controlled sort of a way,” says Hile.

The boys surge to a tub filled with rubber grains. Grabbing models of dinosaur legs, they make tracks and roar, loud as any good T-Rex.

First-graders settled, the volunteer beckons fifthgraders to another tub and hands them graph paper with oversized grids. Paleontologists brush away dirt to find fossils, then record their locations, he explains.

The kids grab paint and try it. When one discovers a nest, another sketches it. The volunteer asks, “What kind of eggs are they?”

The question stumps the junior paleontologists. The volunteer points to a chart. After some discussion they decide they’ve found a Segnosaurus, or slow lizard, nest. This two-legged creature lived in Mongolia 144 to 65 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period. It survived on meat, and possibly plants.

As the fifth-graders finish their research, second- and third-graders climb inside two life-sized models of dinosaur nests filled with Hadrasaur (duckbilled dinosaur) and Oviraptor eggs. Based on real discoveries, the nests sit before a mural of the sunrise over a Cretaceous inland sea shore in New Mexico. Silver City artist Karen Carr created that painting, and another depicting alligators, Pterodactyls, and sauropods by a lake.

Scientists know some dinosaurs hatched their eggs like modern birds. “Prehistoric Playground” has a replica of a fossilized mother on her nest. She’s an Oviraptor, a small birdlike Cretaceous dinosaur that walked on two legs, ate meat and sported a bony crest.

The exhibit contains an additional replica of a fossil called Baby Louie, an unidentified embryo from Hunan, China. Scientists find most baby dinosaurs in jumbled piles. Baby Louie’s bones lie in the position they would have in life. As with the mother Oviraptor, no one knows just how Baby Louie died.

Hile ponders. “One of the fun things about dinosaurs is we get to imagine why it is that we find the dinosaur the way that it is. That’s why I think kids love dinosaurs so much. They get to imagine what the world of the dinosaur was like.”

An exhibit case catches one child’s attention. “What’s that?”

“Read the sign.” A teacher points to a child-level plaque The case holds replica thigh bones of adult and juvenile Apatosaurus (Brontosaurus). The sign explains that dinosaurs grew up like any other babies. Their eggs also came in many sizes, shapes, and thickness.

The roaring robots that caught everyone’s attention at the exhibit entrance let out more yowls. The kids discover they are Parasaurolophus, two-legged duckbilled dinosaurs with long crests on the backs of their heads.

The robots represent babbling toddlers, a fractious roaring teen swinging his tail, and peeping babies popping from eggs.

“I like to imagine what they’re talking about,” Kelly laughs.

She doesn’t have time. The students must enter the museum’s inflatable Star Dome and see the 360-degree movie that goes with the exhibit, “Dinosaur Prophesy.” The film explains the latest theory of dinosaur extinction, an asteroid hitting earth, and suggests ways we might avoid that fate.

The show lasts 20 minutes. Everyone watches, but when the last picture fades, chatter explodes.

“I liked the part when the meteor hit . . . When the dinosaur fell, whoa. . . Dinosaurs weighed a lot of pounds.”

One teacher chuckles. “They learn so much better getting their hands in it rather than reading it from a book.”

“I like the way children’s museums have brought that into the community,” adds Hile.

I second that.