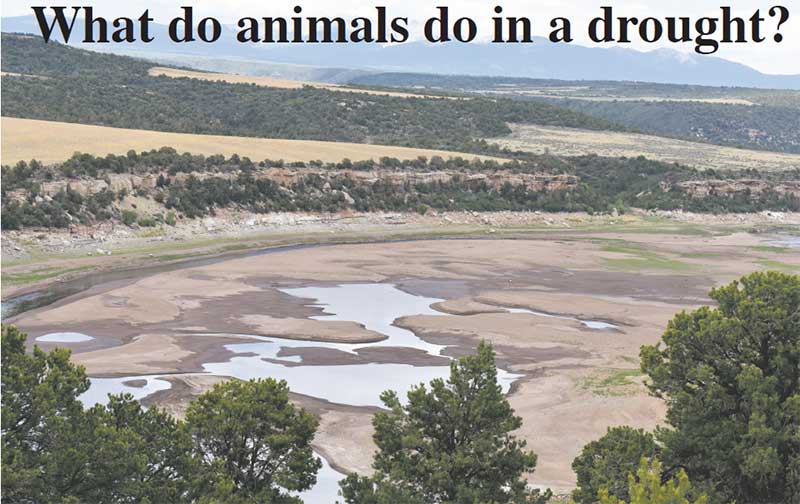

Water in McPhee Reservoir is at a very low elevation and the Lower Dolores River was dry in places at the end of June. Photo by Gail Binkly

In mid-June, a 2-year-old male bear was wandering the streets of Dolores at night, tipping over trash bins that weren’t latched to find himself a meal.

Dolores is the only town in Montezuma County to have an ordinance “requiring all trash containers to be bear-proof and requiring all trash to be stored in bear-proof containers.” Sheriff Steve Nowlin told the Four Corners Free Press that he’s already issued four citations to Dolores residents who have failed to secure their trash.

“Just keep your trash locked up until the morning of trash collection,” he said. “We’ve got more bears coming in and we’re going to have continued problems.”

The drought is helping drive more bears into towns as the bruins face shortages of food and water in the wild. Photo courtesy Warren Holland/BearSmart Durango

Nowlin said the bear was finally caught on Merritt Way at the end of June. It had been trapped and relocated last year, but found its way back to Dolores again this year. So it was doomed.

“It’s not the bear’s fault,” said Nowlin. “Just because he’s hungry and I can’t get people to take care of their trash, Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) had to put him down. The only thing I can do is to try to educate people.”

Nowlin, who was upset about the bear’s fate, told the Free Press that there are more bears in town now, which he believes is because of the drought.

“The natural foods aren’t available right now, and lack of water doesn’t help. Wherever they can find water they’re going to go, and they do come to the river – that’s the natural water source for everything.”

Nowlin said bears are not “true predators” but opportunistic omnivores that will return to a reliable food source once they find it.

“People can avoid these conflicts with these bears,” he said, by making sure they do not feed bears and removing things that attract the bruins, such as trash, bird feeders, and unclean barbecue grills.

The combination of drought, which limits food sources and the nutrient value of forage, and increased human visitation on public lands and national forests has increased the chances that some wildlife may move into human-occupied areas in search of both food and water.

For many people, one of the attractions of living in a rural area is the proximity to wildlife, but “we just don’t want to have them get habituated with humans,” continues Nowlin. Most animals know where the water sources are.

“Birds and other wildlife will definitely come to water,” he said. But what happens when their regular water sources dry up? Some animals, like bears, will venture into human-occupied areas, but others, such as elk and deer, may not.

Brad Weinmeister, wildlife biologist with CPW, told the Free Press that “one of the big things is that there is not the forage that there used to be for wildlife.”

He said it’s difficult to determine the total impact of drought. For example, if there’s a heavy snow and hard winter, it’s relatively easy to find a deer carcass and note that the animal didn’t survive the winter. But the impact of drought is harder to see.

A dry year followed by a wet year allows the plants to regrow, but extended dry years take a toll.

“I’m not sure how they’re making it through some of these years with the poor-quality forage – we haven’t got any new regrowth on winter range and they’re feeding off the same stuff for two years in a row,” said Weinmeister.

Animals need food, water, cover and space. “With drought you take away water, food, you take away their cover – so it’s impacting three of those four main components of habitat. You have poor forage conditions, so the nutrition quality is poor and the animals aren’t as healthy,” Weinmeister said.

There is increased predation on stressed animals, which are likely to be weaker. Weinmeister said that in drought conditions animals will concentrate around seeps and springs, which then makes them more vulnerable. “They’re still using the same areas, but they’re just more susceptible to disease and predation,” he said.

But with the increase in the number of recreational users of the forest as well as houses being built in what is called the “Wildlife Urban Interface” (WUI), “they’re losing their space too,” Weinmeister said.

Thus it is difficult to tease out specific influences on wildlife. “What we’re seeing with elk is that they are reproducing, but the calf numbers are down – the calves aren’t surviving,” he noted.

Most people in the Four Corners region are probably well aware that our area is suffering from an extended “millennial” or “mega” drought – meaning that this is the driest period on record since the 1100s, when the Ancestral Puebloans left, most likely because of extended drought conditions.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines drought as “a period of abnormally dry weather long enough to cause a serious hydrological imbalance.” The “hydrological imbalance” means that drought brings many risks – direct and indirect – to our daily lives.

Food systems for humans, including agriculture and livestock production, are impacted, but drought also brings ecological risks, including fire, as well as economic and political instability.

Mami Mizutori, special representative of the United Nations Secretary-General for disaster risk reduction, has compared the impact of drought to that of a pandemic, stating in the 2021 Global Assessment of Risk Special Report that, “As with Covid-19, droughts affect all societies and economies – urban and rural. The cost of drought to society and ecosystems is often substantially underestimated – drought has been the single longest-term physical trigger of political change in 5,000 years of recorded human history.”

The local drought has indeed brought “political” changes to our region, exemplified by regional entities enacting restrictions on human activity. The San Juan National Forest went under Stage 1 fire restrictions as of June 15, which prohibit “igniting, building, maintaining, or using a fire outside of a permanent metal or concrete fire pit that the Forest Service has installed and maintained at its developed recreation sites.”

Stage 1 restrictions do not prohibit the use of firearms or chainsaws, and smoking is only allowed inside of a vehicle or in a developed recreation site. Stage 2 restrictions are a bit more restrictive, while Stage 3 prohibits any entry into the restricted area.

Mancos instigated an in-town fire ban on June 16, and also has mandatory watering restrictions allowing outside watering only between 6 and 10 a.m. and p.m., with even-numbered addresses only allowed to water on even-numbered calendar days, and odd on odd days.

Dolores implemented voluntary watering restrictions starting on June 28, suggesting that watering be limited to a total of 2 hours and not at all between 11 a.m. and 6 p.m. Similarly, the City of Cortez has voluntary water restrictions in place between April 1 and Oct. 31 that prohibit watering yards and gardens between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m. The city uses the same even/odd system as Mancos. Additionally, Cortez has permanently banned irrigation watering between 10 a.m. and 5 p.m. from May 15 through Sept. 15 every year.

Yet even with these restrictions, people are most likely to have enough water to survive – something not guaranteed for wildlife. Bears will come into human-occupied areas, as will some predators. Mountain lions will follow their prey, which are mostly deer. Weinmeister noted that “the animals that are out on the natural landscape – the national forest – are more impacted by drought. The animals staying on alfalfa fields, or in town or in places with irrigation, are having better reproduction than the animals on the forest. A deer staying on an irrigated alfalfa or hay field has good cover and good nutrition.”

But then the predators enter.

Nowlin told the Free Press, “We’ve had mountain lion sightings in the town of Dolores, on several occasions – a female with kittens is coming in.”

What about fish?

Jordan Fenner, fishing guide for Telluride Outside for the past five years, told the Free Press, “We’re really self-regulating for the health of the trout.”

A “cutbow” (a cross between a rainbow and a cutthroat trout) caught on the Dolores River in July. The river is so low, anglers are being asked not to fish between McPhee Dam and Bradfield Bridge after noon on any days. Photo courtesy Jordan Fenner

This year is the second dry year in a row, and Fenner said “last year we shut down our fishing from the West Fork down to the confluence [of the Dolores], because of how low the water was.”

Low water flows mean higher water temperatures. Fenner explained that trout “are really finicky. They’re an index species because they need their environment to be pretty perfect and it’s a small window for them – between 50 and 60 degrees. I carry a thermometer and pay attention to that.” He said he definitely is aware of the impact of the drought on the fish, and that this impacts how he guides.

“Last Sunday on a section of the Dolores near the Roaring Fork, it was beautiful, amazing really, but the water was so shallow. We got all that rain and the water came up – maybe we got some more time to fish, but it was so skinny and there were many places we couldn’t fish. We started off in a place we normally fish and moved up river looking for water we could fish. We knew where the pools are, but it was a little scary to see how rapidly it dropped out.”

Fenner said heat de-oxygenates the water, which makes it less desirable for the fish, which follow plant life and insects for their sustenance. He can tell the fish are stressed because of how they “habituize,” meaning they have fewer places to hide and are definitely harder to fish because you have to be a better caster and use smaller flies.

“When it’s really hot and really low I just know enough to leave them alone.”

But Fenner said his clients don’t really understand these nuances. “All of our clients now are from out of state – large urban areas in Texas or Arizona – or out of country, which has changed because of Covid. If you told them we’re in a drought, they can’t tell. They’re from these large urban areas and don’t understand the cycles of nature and how things are being affected,” he said.

Fenner hasn’t noticed a drop in clients, but under the current drought conditions his company has started to move over to the Gunnison River to fish instead of the Dolores or the San Miguel, primarily because of the low flows. It’s logistically more difficult, but better for the fish, he said.

Native flannelmouth suckers converge for spawning in the Lower Dolores River in 2006. The suckers are one of three native fish species in the Dolores whose status is of great concern, and the drought won’t help them. Photo courtesy David Graft/Colorado Parks and Wildlife

The Durango CPW district has put voluntary fishing advisories on some of the waters, including the Animas, in order to keep the fish a little less stressed. A healthy trout may be able to survive the catch-and-release technique utilized by fly fishers, but a stressed trout may swim away when released, only to die downstream due to the stress of being caught.

A voluntary fishing closure on the section of the Dolores River from McPhee Reservoir down to Bradfield Bridge from noon through the remainder of the day is currently in place. CPW says it may implement an emergency closure to all fishing if conditions don’t improve.

As of June 30 the dam-regulated flow was 10 cubic feet per second, which is not sustainable for fish. The Dolores River in Dolores was at 25 percent of its average flow during the entire runoff this year, with the Animas, San Juan and other rivers also low.

At the end of June and in early July, the Dolores River was completely dry at Bedrock, upriver from its confluence with the San Miguel River. The flow there was at 0 cfs, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

That’s almost certain to have an adverse effect on three native fish species in the Dolores — the flannelmouth sucker, bluehead sucker, and roundtail chub — about which water managers have been greatly concerned. If the fishes’ numbers nosedive, there is the potential for one or more of the species to gain an endangered listing, which could affect how water is allocated.

The drought also could potentially affect hunting.

Weinmeister told the Free Press he hasn’t really noticed an impact on deer- or elk-hunting due to the drought. However, “last year I noticed a change with bighorn sheep. They were down in lower elevation in timbered areas, instead of staying above timberline, possibly finding seeps in the timber. For sheep hunting, when the animals are down in the timber, it may be harder,” he said.

Mountain sheep, elk, bears, deer, fish, and mountain lions are all definitely affected by the drought, and changes in their behaviors are beginning to be noticed by humans. But what about other, less-noticeable wildlife?

Reproductive rates and the numbers of young in birds and bats are down, but there’s not a lot of long-term data available. Rabbits, squirrels, and other smaller wild animals can’t survive as long without water as larger game animals can. And their numbers are not tracked so the long-term effects of drought remain largely unknown.

One recent news report from an Arizona network said large birds of prey were “dropping from the sky” due to the consistent high temperatures over 115 degrees Fahrenheit.

We do know that as serious the drought is for humans, it is worse for wildlife. How that will change human interactions with the wildlife we love is unknown.

Locally, because of the pandemic and economic incentives promoting tourism, there has been an uptick in visitors to the local area, many of whom come to enjoy our national forests, rivers and wildlands. Hunting and fishing are also major reasons people come to the Four Corners area, and so far the drought has not seriously impacted these activities.

Yet the combination of an extended drought along with an increase in visitation to natural areas is stressing our wildlife.

“Multiple years of drought are definitely going to have an impact on animals,” said Weinmeister, “but it’s hard for us to measure what the total impacts are to wildlife are.”

“There’s a lot of human activity on the forest lands, and it definitely has an impact on wildlife,” Nowlin agreed.

You might be excited or afraid to find a bear or a mountain lion in your backyard, but that is not the animal’s usual habitat, and chances are the creature is trying hard to survive. Living in the rural Southwest means we have to accommodate our wildlife. It’s OK to put out water for animals and birds, but feeding wildlife is illegal and can lead to dire circumstances for both humans and animals. While it may seem helpful to put out hummingbird feeders, they can actually cause more harm by attracting bears. If used at all they should be hung at least 10 feet above ground level.

Interested citizens are encouraged to find out more about what they can do to help drought-stricken wildlife by perusing the CPW, Forest Service and Bear Smart websites.

“Wouldn’t it be a shame if we didn’t have these animals around?” asked Nowlin. “We’ve got to have human participation to keep both humans and wildlife safe.”